Indians Archive

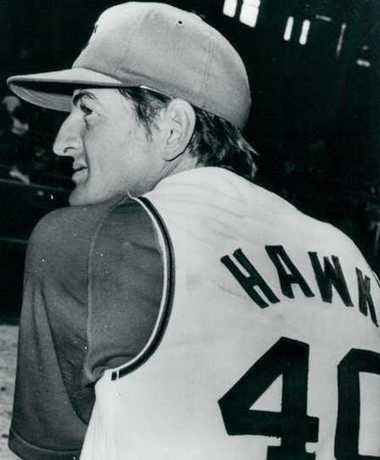

Indians Archive  Cleveland Sports Vault: Hawk Harrelson Joins the Indians

Cleveland Sports Vault: Hawk Harrelson Joins the Indians

I had my preconceived notions about Ken Harrelson. Even though I was a very young kid when he played for the Indians, there’s plenty of information out there today on the flamboyant ballplayer from the 1960s.

I had my preconceived notions about Ken Harrelson. Even though I was a very young kid when he played for the Indians, there’s plenty of information out there today on the flamboyant ballplayer from the 1960s.

“Hawk”, as he is known (even to himself, in the third person), has freely admitted he is not a modest man. He allows he is egocentric, even. Even today, as the current television voice of the Chicago White Sox, he’s a polarizing figure. Even among White Sox fans.

***

Followers of the struggling Cleveland Indians of the 1960s still carried fresh memories of the strong teams of the previous decade. While much of the 1950s were owned by the New York Yankees, the Tribe was very good as well.

The 60s were when Municipal Stadium began to depreciate as a desirable venue for baseball (although for Cleveland football fans, it was terrific all the way until its 1990s demise). It was more than twice the size it needed to be, and the windswept concrete and steel remained cold and damp for much of the season.

Furthermore, the Indians franchise was no longer contending for a pennant; the dozens of crazy Frank Lane trades around the beginning of the decade had shuffled the roster into a mess. Fans stayed away, and the team’s financial position was precarious enough to attract suitors - other cities, such as New  Orleans and Seattle, who longed for a big league baseball team of their own.

Orleans and Seattle, who longed for a big league baseball team of their own.

By the late 60s, Gabe Paul, a lifetime baseball executive, was running the operations of the Indians. He knew northeast Ohio would explode with support if handed a winner. He called Cleveland “a sleeping giant.” Over the years, scribes have treated the comment with an odd admiration, as if he were the only person who saw this. He was right, of course, and it was proved to be true in the 1990s- but all Cleveland fans intuitively knew this. It was obvious. We were always all about emotional support. We complained, we fumed, but we always cared.

By 1969, “Pope” Paul wanted to make a splash. The team, he felt, needed a marquee name. A player with star power, and a personality to match. He learned that Ken Harrelson of the Boston Red Sox was on the trading block.

Harrelson was always a flashy personality, going back to his childhood in Savannah, Georgia. He was drafted by Charlie Finley’s Kansas City Athletics in 1963, and picked up the nickname “Hawk” in the minors. (Cleveland actually had also tried to sign him out of high school, as a pitcher.) He felt the nickname suited his prominent nose, but also his personality. At a very early age, Hawk was interested in marketing his persona, for publicity and possible financial gain. He met the PA announcers in minor league ball parks and asked them to announce him as “Hawk Harrelson.”

He wasn’t fiery, like so many outspoken ball players had been over the years. He was extravagant. Showy.

He loved clothes. His was the “mod” style.

Flashy, fashionable. Opposite of hippie. Mod. In my opinion, it was the 60s’ mods who became the 70s’ disco generation.

Back in the early 60s, many postwar British youth chose to separate themselves between the mods and the rockers. Rockers were masculine, heavy drinkers, whereas mods were stylish, and favored caffeine and amphetamines (check out the movie Quadrophenia, by The Who). By the late 60s, the kids were growing up. At least in the U.S., “mod” became mostly a reference to the Nehru jacket, tight pants look. My impression is that the roughest edge of the rockers started the punk movement.

Hawk borrowed money from Finley- lots of it. He spent much of it on clothes, perhaps partially to compensate for growing up without much money, as the only child of a single mother. To receive payments on the debt, Finley arranged to withhold a certain percentage of the ballplayer’s salary from his paychecks. Hawk also claimed to be capable of augmenting income with some gambling on the side- most likely playing billiards. In fact, among that, cards, football, baseball, basketball, golf, and other activities, he said baseball wasn’t what he was best at. It was third, behind basketball and football.

In 1966, Hawk’s new manager in Kansas City was Alvin Dark. The two understood each other, and got along great. Hawk was traded to the Washington Senators later that season, only to be reacquired by the A’s in 1967. The A’s’ players were disenchanted with the unpredictable Finley, who exacerbated the situation with his eventual firing of Dark.

In retrospect, it seemed inevitable: when Dark was let go, Hawk Harrelson lashed out. The media reported that he stated Finley was a “menace to baseball.”

The owner was not amused. He demanded a full retraction, and when that did not happen, he summarily “fired” Harrelson.

The owner was not amused. He demanded a full retraction, and when that did not happen, he summarily “fired” Harrelson.

It was almost unheard of- Hawk was a productive player, approaching his prime, and his contract was team-friendly. But now, he was a free agent.

He almost signed with the Atlanta Braves, before settling on the Boston Red Sox. In the process, he saw his salary jump from $12,000 to $150,000. An avalanche of endorsement and other ancillary opportunities began to open up for him, as well. Boston was where Hawk Harrelson figured he was meant to be.

Until April 19, 1969, that is. That was when Harrelson received a call from Alvin Dark. Dark was managing the Cleveland Indians now, and was beyond excited. The two were going to be reunited. Hawk had to admit- the Red Sox got a good deal. They had traded Dick Ellsworth, Juan Pizarro and Harrelson for up-and-coming starting pitchers Sonny Siebert and Vicente Romo, along with seasoned catcher Joe Azcue. The Red Sox needed pitching, and traded hitting to get it.

Harrelson’s life was in Boston- his business interests such as his clothing line, his friendships… He had money now, and didn’t need baseball. He was going to retire. A press conference was held, and he made the announcement. Someone asked – if the Indians made up the money he’d lose by leaving Boston, would he change his mind about retiring?

Gabe Paul met with Harrelson, and asked him to report to the team. He offered no further incentive, only a sense of duty. That didn’t work. The next day, commissioner Bowie Kuhn placed a call to Hawk’s agent, requesting a meeting. It was there that Paul, the Red Sox GM, and Harrelson came to an agreement. The player, after all, owed everything he had to baseball, and the Indians were willing to ramp up his pay and extend his contract. Hawk agreed to play with the Indians. Kuhn was pleased- he said baseball “needs” the Hawk.

The assumption I always have had is that Hawk Harrelson felt he was too good for Cleveland, and couldn’t wait to get out. After all, he was going to retire,  rather than comply. It seemed he had to be begged to report.

rather than comply. It seemed he had to be begged to report.

I guess I now view that in a new light. He thought his old friend (and Indians catcher) Duke Sims was going to be his welcoming party at Hopkins airport. Sims was there – along with television and radio stations, and a thousand fans chanting, “Hawk, Hawk, Hawk.”

Hawk Harrelson ate it up. He was cheered and greeted everywhere he went. Several business deals were already being worked up, including a Harrelson’s of Cleveland clothing store, a club named Hawk’s Nest, and a regular local television show. Former Indians star Al Rosen was working on financial matters. The team hired a staff for Harrelson- a guy to handle his affairs at the stadium, and a secretary to answer his cascade of mail. He was set up in Indians owner Vernon Stouffer’s new apartment tower (Browns owner Art Modell also lived there, at the time). The structure had a helipad on the roof, and Stouffer offered Hawk the use of the helicopter for travel to the stadium. (Wow.) Harrelson’s Boston houseboy came to Cleveland, to work for Hawk there.

In Harrelson’s first season as an Indian, he started fast before hitting a severe slump. He did finish with 30 homers, 92 RBIs, and 17 stolen bases while playing on the worst team in the majors.

In spring training prior to the 1970 season, he broke a leg while sliding. He missed all but the final 17 games of that season. 1971 was the year Chris Chambliss broke in with the Tribe. Chambliss took over first base, winning the American League Rookie of the Year Award.

During the 1971 season, Hawk Harrelson retired from baseball. He left the Indians on less than favorable terms, and joined the pro golf tour. Eventually, he became a baseball broadcaster, and served as the Chicago White Sox’s general manager for a time.

***

Yeah… he was a self-promoter. People who liked him called him a ham. Shoot, he called himself a ham. Those who disliked him saw him as a narcissistic blow hard. Truth be told, both sides were right.

Sources included Tales From the Tribe Dugout and The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia, Russell Schneider; Wikipedia; baseball-reference.com; Hawk by Ken Harrelson and Albert Hirschberg; SI Vault online.

***Hey, follow me on Twitter! http://twitter.com/googleeph2 #thanks

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)