Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Cleveland Sports Vault: WWII, Baseball, and Local Boy Paul O’Dea

Cleveland Sports Vault: WWII, Baseball, and Local Boy Paul O’Dea

In times of war, the court of public opinion begins to coalesce. Should “non-essential” activities, such as sporting events, be postponed? Perhaps canceled?

In times of war, the court of public opinion begins to coalesce. Should “non-essential” activities, such as sporting events, be postponed? Perhaps canceled?

We’ve seen brief postponements result from weather-related disasters, such as from a hurricane making landfall. When the country is on a war footing, however, the real debate is engaged: should the non-essential activity of professional sports take a hiatus?

This had been thoroughly discussed during World War I. Secretary of War Newton D. Baker had issued his “Work or Fight” edict, causing ripples of uncertainty throughout Baseball. However, American League president Ban Johnson reminded that during the Spanish-American War (1898), the National League did not suspend play.

While the threat and the battles of WWII had been ramping up for years, the U.S. was drawn into the mix when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, in Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. In the days and weeks that followed, many of Baseball’s greatest players- including the Cleveland Indians’ Bob Feller- enlisted in the service. However, there were enough big leaguers still in the game that it seemed little had changed.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt (whom had led some of Baseball’s military drills, years earlier) was clearly in favor of the continuation of play, citing civilian morale. His stance trumped those of various other public officials, who made clear their view that the game was not “essential.”

When his first player was drafted for World War II, Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith protested. He argued that neither the game, nor ballplayers’ skills, could transfer to the war effort. He also spoke about the “social harm” that would befall society, were the game to be canceled. Griffith’s opinions carried weight; he was publicly involved in patriotic activities such as in the sale of war bonds. As part of a compromise, Griffith had teams performing military drills prior to games- using bats as ‘rifles.’

1944 was when the war caught up to Baseball. Well over half of the 1941 starting lineups were now gone. Cleveland owner Alva Bradley maintained that the season would not survive the attrition, saying if he couldn’t field a professional quality team, he would close his doors.

Baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis reined in spring training. National restrictions on travel was one reason, but Landis also wanted to avoid the public image of “athletes lolling about on the sands in some semitropical climate” while servicemen and civilians alike were carrying the burdens of war. He mandated that training would be north of the Mason Dixon line, and east of the Mississippi River. The Indians searched for a locale that boasted a large field house, for use as shelter from the weather. They chose Purdue University in Lafayette, Indiana- but it wasn’t until they arrived that they learned they could  not use the field house until classes were over at 4:30 each day.

not use the field house until classes were over at 4:30 each day.

Baseball camps were inundated with those hopeful of earning a roster spot (the Indians ran out of uniforms). Mostly, they were teenagers and 4Fs (a U.S. military classification for those men not acceptable for service). Teams began to consider a 4F as a plus- perhaps somewhat similar to how today’s general managers view a healed Tommy John pitcher. Rosters were stocked with players who were too tall for the service, who were hard of hearing, who had less than five toes on a foot...

(The minor leagues took a severe hit. Young ballplayers were likely in the armed forces, and older men were commonly able to earn much more money in the defense industry than as a minor league ballplayer.)

The Indians’ manager during WWII was shortstop Lou Boudreau (right, with Bradley). He was only 24 years old in 1941 when he’d lobbied for, and was awarded, the manager’s job. Cleveland had been known as the “graveyard of managers”, notably releasing the abrasive Oscar Vitt after the “Cleveland Crybabies” player rebellion of 1940 and then the immensely popular Roger Peckinpaugh.

But Pearl Harbor was attacked two weeks after Boudreau took the job, and he immediately lost Feller to the war. The season seemed to end almost before it started.

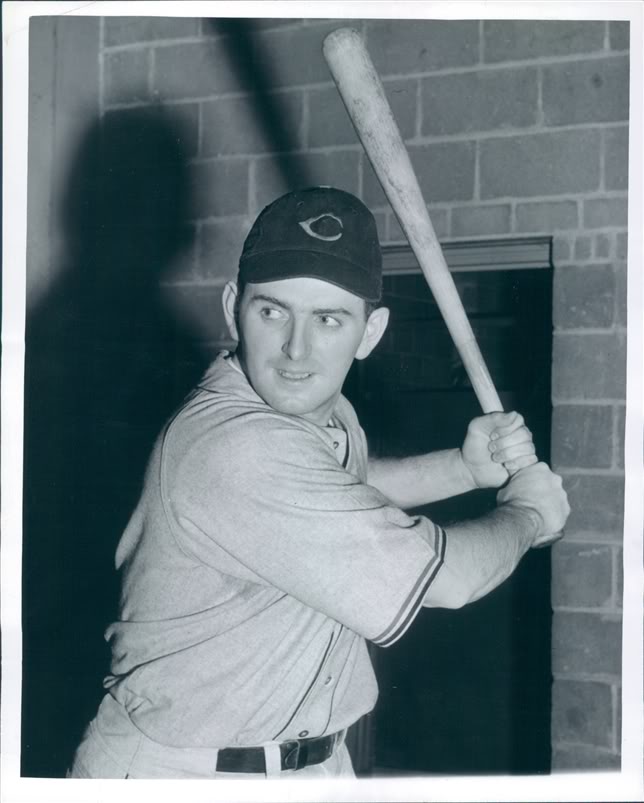

Over the next couple years, there were bright spots. One talented youngster the Indians had been counting on for the 1940s was Paul O’Dea. One of many local products of the 20th Century, the West Tech High School graduate attended Tribe camp as a nineteen year old in 1940. As he leaned around the edge of the cage during batting practice, a fellow rookie fouled off a pitch- directly into O’Dea’s right eye. He underwent several surgeries, and lost sight in the eye.

O’Dea was determined to keep playing, and the Indians followed his progress as he excelled on the Cleveland sandlots over the next couple seasons. In Baseball’s talent-lean season of 1944, O’Dea stuck on the Tribe roster. All observers knew his history, and he was an inspiration.

O’Dea was determined to keep playing, and the Indians followed his progress as he excelled on the Cleveland sandlots over the next couple seasons. In Baseball’s talent-lean season of 1944, O’Dea stuck on the Tribe roster. All observers knew his history, and he was an inspiration.

O’Dea was in the starting lineup on Opening Day in 1944, manning left field. His first hit – and first RBI - came in a pinch-hitting role during Cleveland’s first win of the season, a 5-1 decision over the Browns in front of 1,106 in St. Louis. (The St. Louis Browns, a perennial American League doormat, would actually win the World Series in 1944. Cleveland football fans appreciate the irony that eventually, the Browns were moved to Baltimore.)

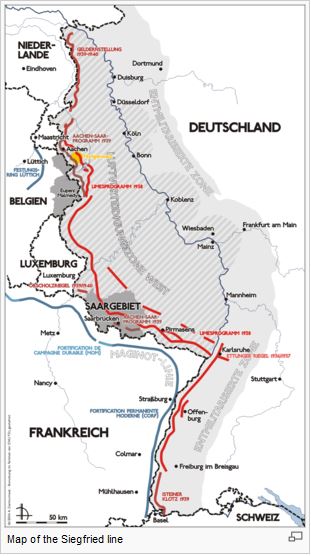

For much of 1944, the U.S. was buoyed by success in the war. By the end of the World Series, the Allies had penetrated Germany’s Siegfried Line (right, from Wikipedia), a line of forts and tank defenses designed to protect the

However, soon came the Battle of the Bulge, a German offensive in a weak section of the Allied advance. It was a bitter, protracted, sobering response to the Allies’ movement eastward. American optimism reverted to grim determination. The continuation of big league baseball found itself in its most serious moment of jeopardy. After all, the men playing the game had proven they were physically fit and able. And it appeared the country needed them.

Of course, 1945 was a whirlwind, historically. The Allies regained the upper hand over the Axis. Roosevelt died in April, V-E Day (victory in Europe) was in May, and Harry Truman finished the war with the atomic bombs on Japan in August. For baseball, the stars- who had been playing ball through the war, at military installations- began to trickle back to the big leagues.

In his two – year career, Paul O’Dea appeared in 101 games, mostly in right or left field. He had a good arm, and actually pitched in four games. One such contest was in July, 1945 at Fenway Park. The Indians had handed starter Allie Reynolds a four run lead in the first inning. Reynolds allowed the Red Sox to load the bases, before going 3-0 to Bobby Doerr. Boudreau sent Reynolds to the showers. Doerr greeted reliever Paul Calvert with a grand slam to tie the game. Calvert surrendered six more runs, and Boston won the game, 11-7. Pat Seerey, Ken KeItner, and Lou Boudreau (2) all homered for the Indians. In a mopup role, Paul O’Dea pitched three innings of shutout baseball.

The Indians finished in fifth place, out of eight, in both 1944 and 1945. The ’44 season was particularly painful- the team was voted by the sports writers of the Associated Press as the most disappointing team in Baseball after having lost the pennant by one game in the prior season.

So the National Pastime was never interrupted, although it did experience a darkest-before-the-dawn moment- mirroring the rest of the country. The game adjusted, including the use of replacement players such as Paul O’Dea, a local hero who was an inspiration in a time of trial.

Sources included the SI Vault (online), baseball-reference.com, The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia, by Russell Schneider, December 1941: 31 Days that Changed America and Saved the World by Craig Shirley, baseball-almanac.com, Wikipedia.

***Hey, follow me on Twitter! http://twitter.com/googleeph2 #thanks

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)