Indians Archive

Indians Archive  Cleveland Sports Vault: 1974/ '75. Frank Robinson Joins Gaylord Perry’s Indians

Cleveland Sports Vault: 1974/ '75. Frank Robinson Joins Gaylord Perry’s Indians

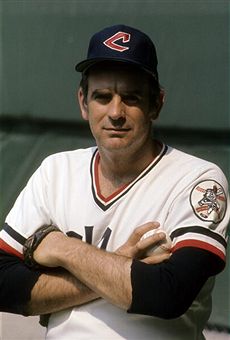

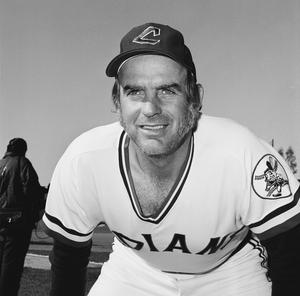

They hated each other. It was hardly a secret, from their days in the National League in the early 1960s. Gaylord Perry had been the talented pitcher of the San Francisco Giants; Frank Robinson, the five-tool outfielder of the Cincinnati Reds.

They hated each other. It was hardly a secret, from their days in the National League in the early 1960s. Gaylord Perry had been the talented pitcher of the San Francisco Giants; Frank Robinson, the five-tool outfielder of the Cincinnati Reds.

The narrative came easily: the fiery, outspoken black child of the U.S. civil-rights era vs. the white farm boy from the deep South. But was that fair?

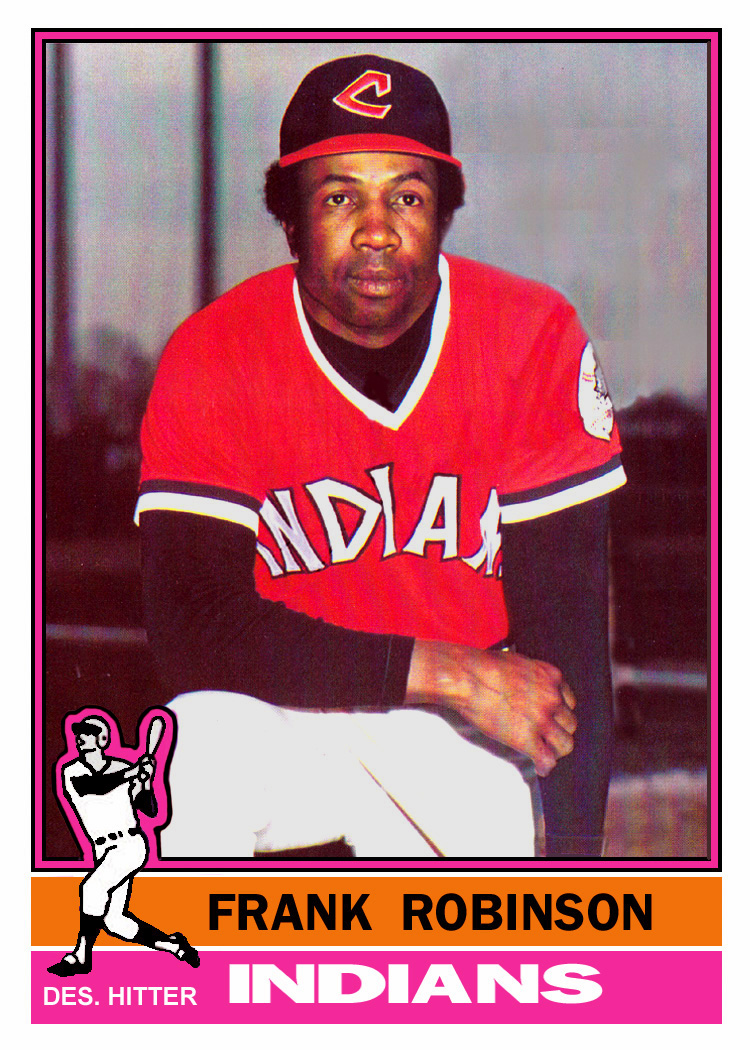

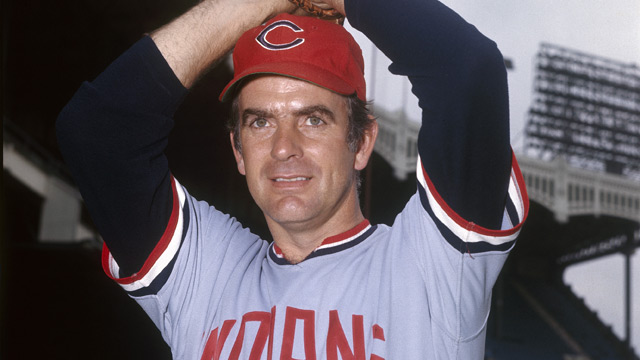

By 1974, each player had been at the top of his profession. Frank Robinson was a 14-time All Star who had been MVP in both leagues. He won the American League Triple Crown in 1966. It’s had to believe today how such a player could be underrated. Once Hank Aaron passed Babe Ruth on the career home run list, a full generation of fans could recite the top four. Aaron, Ruth, Mays, and Frank Robinson. His career was one for the ages.

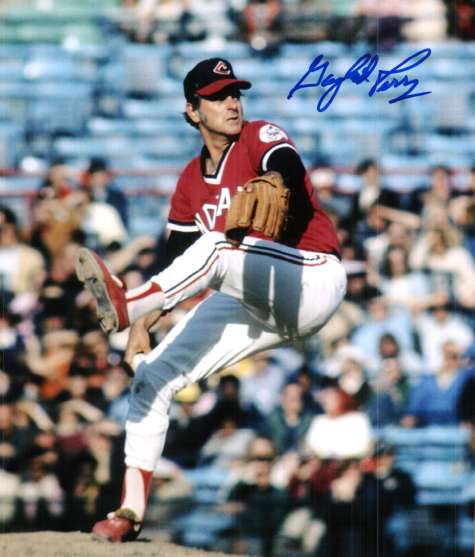

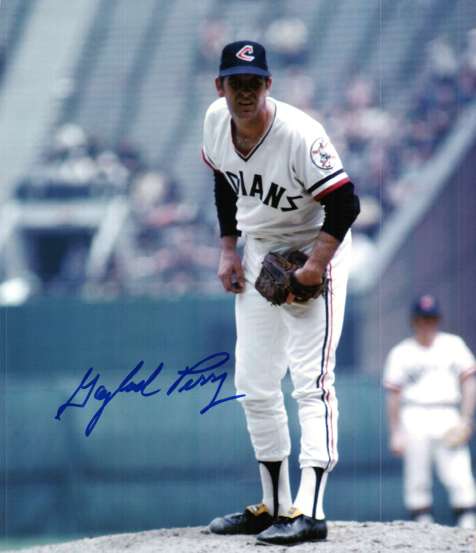

Gaylord Perry had been acquired by the Cleveland Indians after the 1971 season. The Giants coveted the elite power arm of the Tribe’s Sam McDowell, and

were willing to part with Perry and defensive-minded shortstop Frank Duffy. All Perry did in 1972 was win the A.L. Cy Young Award for the last-place Indians. On the season, he went 24-16 with a 1.92 ERA, and 29 complete games (he averaged just under 28 CG per year from 1972-1975). He even saved a game! Fan interest in Perry’s 1974 season caught fire, as he approached Johnny Allen’s 4-decade-old team record of 16 straight wins. He would win 15 straight.

were willing to part with Perry and defensive-minded shortstop Frank Duffy. All Perry did in 1972 was win the A.L. Cy Young Award for the last-place Indians. On the season, he went 24-16 with a 1.92 ERA, and 29 complete games (he averaged just under 28 CG per year from 1972-1975). He even saved a game! Fan interest in Perry’s 1974 season caught fire, as he approached Johnny Allen’s 4-decade-old team record of 16 straight wins. He would win 15 straight.

A big problem with the Indians circa 1974 was the lack of starting pitching behind their ace. There was Jim Perry, the more easygoing, older brother of Gaylord’s. Former Yankee Fritz Peterson was the nominal Number Three, but seldom pitched like one.

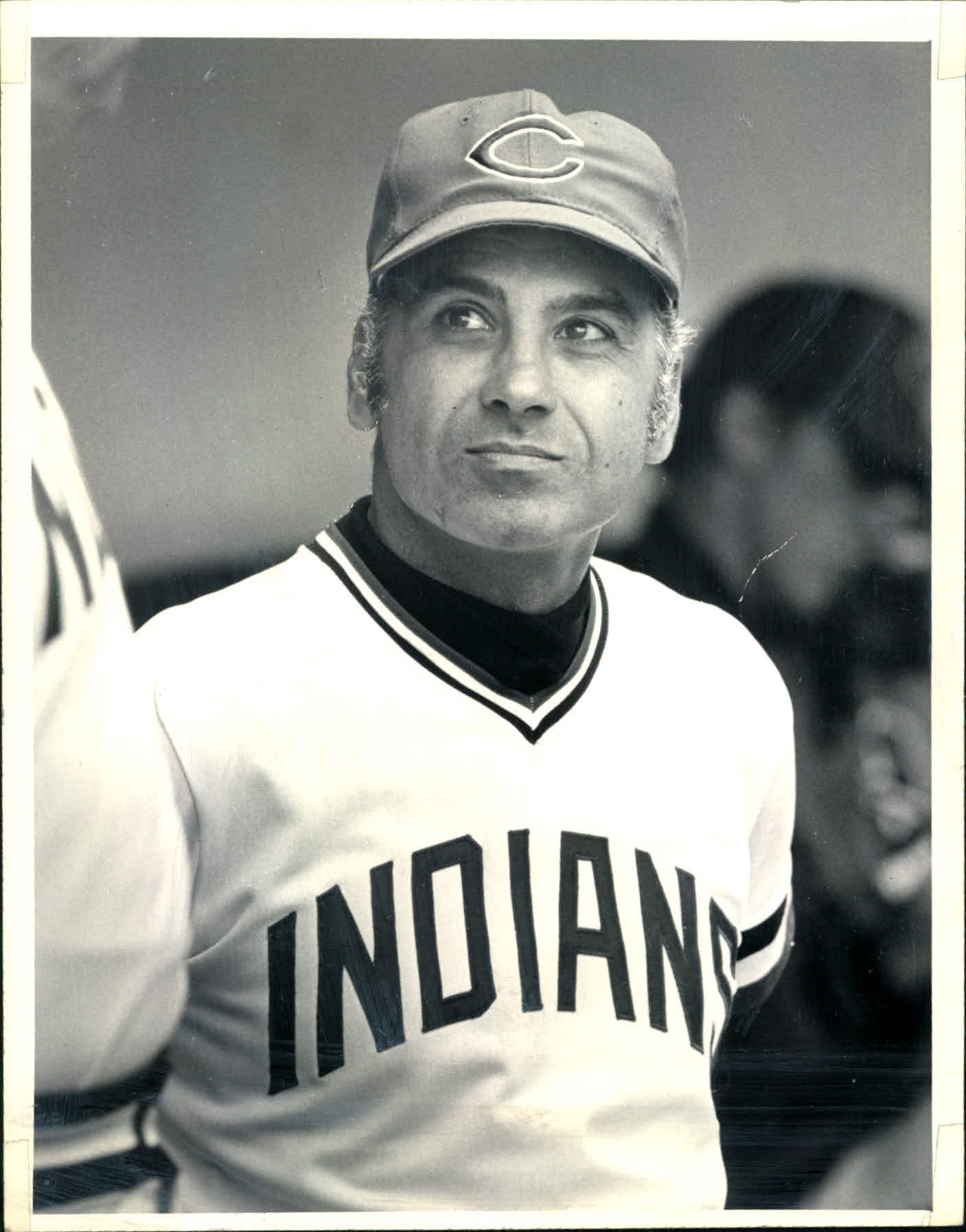

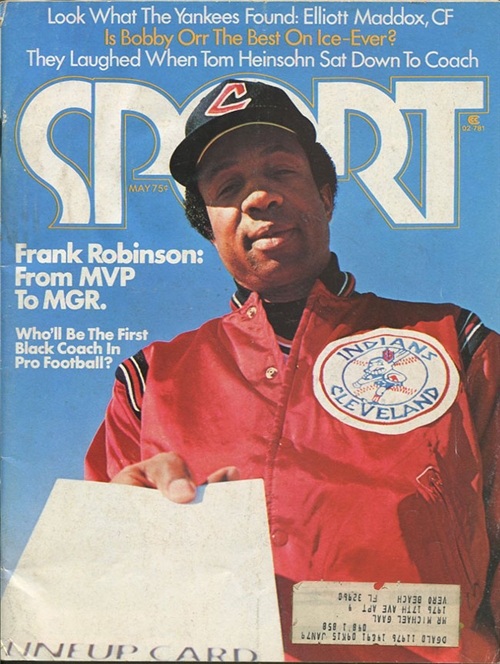

Regardless, manager Ken Aspromonte had his Indians within shouting distance of first place, into September that season. Around this time, the California Angels placed Frank Robinson on waivers. Tribe general manager Phil Seghi picked up the veteran hitter on September 12, ostensibly as a “right handed bat” for the pennant race. Immediately, there were whispers- denied by all parties- that Robinson had been brought in to eventually manage the team. Aspromonte believed the rumor.

The Tribe, 71-71 on the day Robinson was acquired, proceeded to finish the season in a free fall. They lost 14 of the final 20 games to finish 14 games behind the Baltimore Orioles. On September 27, during a rain delay, Aspromonte confronted Seghi. Was he going to be back as manager in 1975? Seghi told him no- but he felt it best for all parties to make the announcement in a week or so, after the end of the season.

“Aspro” (left) was distressed. He retired to his office. It was then that he heard the shouting from the clubhouse.

“Aspro” (left) was distressed. He retired to his office. It was then that he heard the shouting from the clubhouse.

Some accounts hold that Perry and Robinson were close to blows; instead, it seems clear that Perry remained seated as Robinson exploded. The slugger had read a quote by the pitcher in the newspaper, to the effect that Perry was planning to demand “the same salary, plus a dollar more” than the $173,500 that Robinson was earning. Robby took that personally.

Joe Lis’ locker was in between the two. In front of the team, he stood up to Robinson, asking him to take his problems with Perry outside. The team didn’t need more trouble. (Unfortunately for Lis, his future manager seemed to hold a grudge against him. Lis was eventually selected by the Seattle Mariners in the 1976 expansion draft.)

The two “combatants” were ultimately separated by Aspromonte. It was then that the other shoe fell: he announced that he would not be returning as the manager of the Cleveland Indians (the timing enraged Seghi).

Sportswriters quickly learned of the dispute. The following day’s headlines, trumpeting both the quarrel and the manager’s news, owed themselves to the access the press received during the rain delay.

To Robinson, the issue was now in the past. Perry? That wasn’t so clear. Robby liked to get things off his chest- but Perry appeared content to play sides against each other in a passive – aggressive manner.

This remained so, into training camp in 1975. Frank Robinson was now manager, the first black manager in the big leagues.

A pattern emerged. Frank Robinson set the rules and outlined his expectations. Gaylord Perry quietly undermined his authority. An example was their views of the team’s conditioning program. Perry (not exactly an icon of physical fitness) had his own way of getting into playing shape. He preferred to run sprints, and work on fielding ground balls. Robinson had the entire team running 15 times from foul pole to foul pole, with some backwards running thrown in for good measure. Also, pitchers were forbidden to take infield practice.

A pattern emerged. Frank Robinson set the rules and outlined his expectations. Gaylord Perry quietly undermined his authority. An example was their views of the team’s conditioning program. Perry (not exactly an icon of physical fitness) had his own way of getting into playing shape. He preferred to run sprints, and work on fielding ground balls. Robinson had the entire team running 15 times from foul pole to foul pole, with some backwards running thrown in for good measure. Also, pitchers were forbidden to take infield practice.

Robinson wanted the entire team to abide by the same rules. Perry’s response (to a reporter, not to his manager)? “I am nobody’s slave.” (Alrighty, then. Hit that hot button, Gay.)

Interestingly, while the manager held deep grudges from various other feuds within the team, he never seemed to really let his ace pitcher get to him. For his part, Gaylord Perry remained a subversive force throughout the early part of the 1975 season.

He questioned Robinson’s handling of veterans and younger players alike. He questioned the manager’s selection of team captains. He coyly courted other teams, like the Boston Red Sox and the Texas Rangers- places to where he was interested in playing.

Phil Seghi eventually did trade Perry. He actually traded both brothers, prior to midway through the season. Sure, personality conflicts contributed heavily to this, but the fact was neither pitcher had been effective. The team was in last place when Gaylord was traded in late June, at 23-32.

The team would find leadership in veterans such as Buddy Bell, Rico Carty, and newcomer Boog Powell. Also, relief pitcher and Indians Man of the Year Dave LaRoche. The big story, however, was the infusion of exciting, confident, youthful players who began making the move from the minor leagues: pitchers Dennis Eckersley and Eric Raich, catcher Alan Ashby, second baseman Duane Kuiper, and center fielder Rick Manning. Their energy and their eagerness to please their manager were contagious.

The team would find leadership in veterans such as Buddy Bell, Rico Carty, and newcomer Boog Powell. Also, relief pitcher and Indians Man of the Year Dave LaRoche. The big story, however, was the infusion of exciting, confident, youthful players who began making the move from the minor leagues: pitchers Dennis Eckersley and Eric Raich, catcher Alan Ashby, second baseman Duane Kuiper, and center fielder Rick Manning. Their energy and their eagerness to please their manager were contagious.

Overall, the season was rough, despite some notable highlights. The Indians’ record after June 21 was 55-41, and they ended up 79-80 for the year. Frank Robinson was rehired for the 1976 season.

Although he’d been dealt by the Tribe, Gaylord Perry’s career was not over. He enjoyed varying degrees of success with a half dozen different teams, and won another Cy Young award- this time, in the National League, with San Diego, in 1978.

Back in Cleveland, some feel that had they cooperated with each other, leading the team in a unified manner, the Indians of Gaylord Perry and Frank Robinson had a chance to be a legitimate contender.

To be certain, the two alpha males of the 1975 Cleveland Indians were opposites, culturally and personality-wise. In other ways, they were very much alike: prideful, hyper-competitive, and driven.

The result was a power struggle that resulted in a mid-season implosion.

Sources included Frank, the First Year by Frank Robinson and Dave Anderson; Frank Robinson, the Making of a Manager by Russell Schneider; Whatever Happened to Super Joe..., by Schneider; The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia, Schneider; Me and the Spitter, by Gaylord Perry and Bob Sudyk; baseball-reference.com; SI Vault online; Wikipedia.

***Hey, follow me on Twitter! http://twitter.com/googleeph2 #thanks

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)