Boxing/MMA

Boxing/MMA  Boxing Archive

Boxing Archive  Cleveland Sports Vault: 7/3/31. Stadium Opens to Schmeling vs. Stribling for Heavyweight Title

Cleveland Sports Vault: 7/3/31. Stadium Opens to Schmeling vs. Stribling for Heavyweight Title

Many Tribe fans know of League Park, a cozy baseball venue nestled in an east-side neighborhood dating back to the late 1800s. It was land-locked amid properties that were not for sale; this had not been a problem during the heyday of the streetcar. With the boom of the privately owned automobile in the early part of the 20th Century, however, the lack of parking areas became a logistical nightmare during Indians games. The 27,000 capacity limited attendance on some days, as well.

Many Tribe fans know of League Park, a cozy baseball venue nestled in an east-side neighborhood dating back to the late 1800s. It was land-locked amid properties that were not for sale; this had not been a problem during the heyday of the streetcar. With the boom of the privately owned automobile in the early part of the 20th Century, however, the lack of parking areas became a logistical nightmare during Indians games. The 27,000 capacity limited attendance on some days, as well.

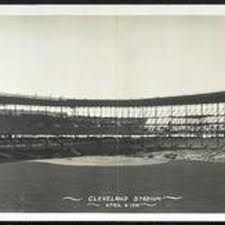

Municipal Stadium, built on a landfill on the downtown lakefront, was heralded as a state-of-the-art replacement for League Park. Built by Cleveland’s Osborne

Engineering Company (the same company that would one day raze it), its size dwarfed most other venues around the country (except for the Los Angeles Coliseum), and the banks of lights atop the facility held the promise of nighttime events.

Engineering Company (the same company that would one day raze it), its size dwarfed most other venues around the country (except for the Los Angeles Coliseum), and the banks of lights atop the facility held the promise of nighttime events.

But moving to the new park wasn’t an automatic transition for the Indians. They still owned League Park; Municipal Stadium was public-owned. $2.5million had been raised through bonds in 1928 (which was just before the 1929 stock market crash that signaled the advent of the Great Depression). The final cost ran to $3million. The time it took to build was 370 days (that is not a typo). When it was completed, there still was no lease agreement between the city and Indians president Alva Bradley.

The stadium was actually one component of a huge development plan throughout downtown. The library, city hall, and the public mall were among the other projects that were involved as well. Also, the rumor that the stadium was built as part of a bid to host the 1932 Olympics is untrue. Cleveland historian Jim Toman notes that this myth may have been borne of the huge edifice being called “Olympic-sized”, and may be the origin of the “mistake by the lake” phrase.

So baseball would not be played in the stadium until 1932, and League Park would continue to host games in which lower attendance was expected (like week-day games) for several more seasons.

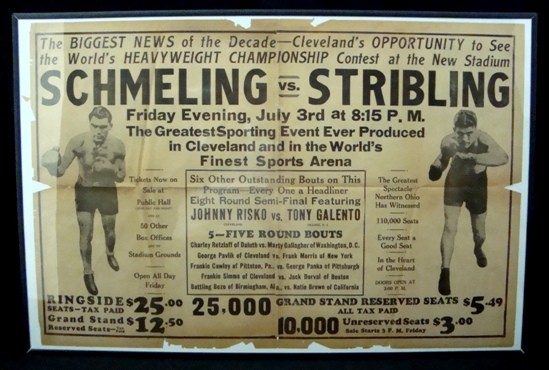

The dedication of Municipal Stadium was held on July 1, 1931. Its first event was a championship boxing match.

Boxing was perhaps the most popular sport in the U.S. by this time. Baseball was huge, and would soon surpass boxing- but not by much, through the 1940s.  Ethnic pride and rivalries fueled interest, and the only way to see a boxing match in the pre-television era was by attending in person.

Ethnic pride and rivalries fueled interest, and the only way to see a boxing match in the pre-television era was by attending in person.

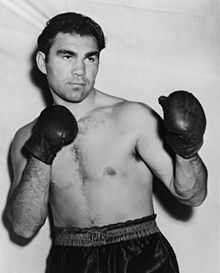

German Max Schmeling, the “Black Uhlan of the Rhine” (‘uhlan’ meaning ‘warrior’), would one day fight the legendary Joe Louis twice, the second of which is known as the “Fight of the Century. But as early as 1931, Schmeling was the heavyweight champion of the world.

However, he was not viewed as an honorable champ.

In the late 1920s, Schmeling won the German title before going on to conquer Europe. His style was methodical and calculated, based on counterpunching. He began fighting in the United States, though he was generally dismissed by the fighting world as a non-contender. He rose in stature as he won bigger and bigger fights, until he surprised contender Johnny Risko in 1929 with a technical knockout after knocking him down four times. He began to be heralded as someone to watch.

After another impressive win, Schmeling had the opportunity to fight the biggest bout of career, to date. His opponent would be Jack Sharkey (“The Boston Gob”), in a match that would determine the champion of the heavyweight division (champ Gene Tunney had recently retired, creating a vacancy). Entering the fourth round, Schmeling was slightly behind. As he drove Sharkey into a corner, Sharkey threw an uppercut that landed below the belt. Schmeling reached for  his groin and fell to the mat as his manager entered the ring to protest. The referee ended up disqualifying Sharkey, and the match became known as the only time a heavyweight championship was decided on a foul.

his groin and fell to the mat as his manager entered the ring to protest. The referee ended up disqualifying Sharkey, and the match became known as the only time a heavyweight championship was decided on a foul.

The champion Schmeling lacked the respect of boxing observers both in the U.S. and in Europe. He was known as the ‘low blow champion’- he hadn’t earned it. Sharkey was vocal in declaring he was getting close to knocking out Schmeling- why would he have purposely fouled? Sharkey dismissed Schmeling’s ability as a boxer. It was supposed to be Schmeling’s proudest moment, yet he was the target of scorn. Despondent, he temporarily planned to decline the championship. Instead, he was persuaded to agree to another match.

Max Schmeling’s next fight was to be held versus W.L. “Young” Stribling.

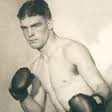

“Young” Stribling was a Georgian who had been literally raised in vaudeville. His family were acrobats, and he joined the act at age four, ‘sparring’ in oversized  gloves with his younger brother. Audiences loved that.

gloves with his younger brother. Audiences loved that.

As he grew older, Stribling fought anyone who would take him on. His father encouraged this. He seldom lost, and turned professional at the age of 16 (hence his nickname). As he grew, he moved on to higher weight divisions, becoming a heavyweight in 1929 when he was  25 years old. Stribling had many interests; he was an active lodge member, and helped disadvantaged children. He was a lieutenant in the Army Reserve Air Corps, and performed feats of skill and daring as a pilot. Known as “King of the Canebreaks” for having landed his plane in a rural field, he also once flew in a circle around the Empire State Building in New York.

25 years old. Stribling had many interests; he was an active lodge member, and helped disadvantaged children. He was a lieutenant in the Army Reserve Air Corps, and performed feats of skill and daring as a pilot. Known as “King of the Canebreaks” for having landed his plane in a rural field, he also once flew in a circle around the Empire State Building in New York.

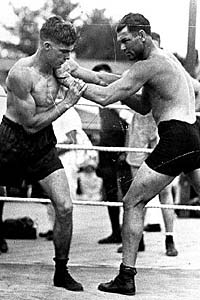

When Stribling and Schmeling were training for their fight (photo at right is of Stribling sparring with Jack Dempsey), Stribling buzzed the Schmeling camp in his plane. He cut the engine, and as he quietly glided overhead, he was heard hollering at the champion.

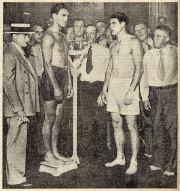

The championship bout between Schmeling and Stribling was held in Cleveland, at the newly built stadium. It was the first boxing match to be broadcast live on radio. Characteristically, Max Schmeling was cautious  and tentative over the first five rounds. Stribling was the aggressor, until his energy began to wane. Schmeling then began to attack. In the fifteenth and final round, Stribling was spent, and he appeared to be just trying to hang on. With only a few seconds left in the bout, he retreated, facing his corner. He staggered, and the referee stopped the fight as Stribling fell, face-first. Once he rose to his feet, Schmeling lifted him and carried him to his corner in a demonstration of sportsmanship.

and tentative over the first five rounds. Stribling was the aggressor, until his energy began to wane. Schmeling then began to attack. In the fifteenth and final round, Stribling was spent, and he appeared to be just trying to hang on. With only a few seconds left in the bout, he retreated, facing his corner. He staggered, and the referee stopped the fight as Stribling fell, face-first. Once he rose to his feet, Schmeling lifted him and carried him to his corner in a demonstration of sportsmanship.

Some felt that Schmeling had fought his best fight. He did feel that he had something to prove to his detractors.

"Young" Stribling’s promising career- and life- ended in 1933. As was his custom, he was riding a motorcycle. He was waving to a friend in a car, and hadn’t noticed another oncoming vehicle. He was run over, and his injuries included a fractured pelvis and a leg that was nearly severed. He underwent an amputation, and a systemic infection developed. Outwardly, he put on a brave front, but his body temperature was shockingly high. He eventually died from his injuries.

In 1933, Schmeling lost to Max Baer. He went on to defeat Joe Louis, “The Brown Bomber”, in 1936. Americans were wary of the Hitler-led Germans, and  nationalism swayed them against him. (Baer, a non-practicing Jew, wore the Star of David on his trunks when he fought Schmeling). He famously studied film of the contender from Detroit, and exploited a weakness he spotted- Louis left himself unprotected after throwing his left jab. Schmeling responded to every Louis jab with a powerful right cross. Schmeling knocked out Louis.

nationalism swayed them against him. (Baer, a non-practicing Jew, wore the Star of David on his trunks when he fought Schmeling). He famously studied film of the contender from Detroit, and exploited a weakness he spotted- Louis left himself unprotected after throwing his left jab. Schmeling responded to every Louis jab with a powerful right cross. Schmeling knocked out Louis.

Schmeling was now solidly in favor with Hitler and the Nazis. He had lined himself up to fight champion Jim Braddock, but Louis was awarded the fight due to the unspoken political nature of Schmeling’s nationality. Schmeling faced Louis in 1938, in The Fight of the Century. In the first round, Louis connected with a devastating kidney punch, leaving Schmeling screaming in pain as he faced the ropes. He was weakened, and Louis won by knockout.

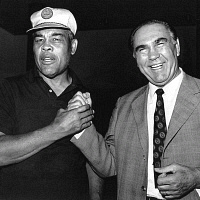

Schmeling’s life took many twists. He fought for his country, and at one point was said to have fallen out of favor with the Nazis. A rumor from the island of Crete held that he had been taken prisoner, became belligerent, and was shot and killed. He surfaced a few months later- apparently, once he had gone missing, the Nazis had spread the rumor of his demise (he apparently had been battling a jungle illness in a remote hospital facility). Schmeling also risked his life in protecting two Jewish children from being taken away from Berlin. After the war, he would become lifelong friends with Joe Louis, until Louis died in 1981. Max Schmeling eventually became a Coca Cola executive, and lived his later years as a heralded hero of Germany. He died in 2009. The Berlin mansion in which he once lived is today the Libyan embassy in Germany.

Max Schmeling outlived his generation’s war. He also outlived Cleveland Municipal Stadium, the place where Cleveland’s Indians, and eventually her Browns, called home for 64 years. For its opening in 1931, it was the world’s stage . The place where Max Schmeling and “Young” Stribling experienced one of the watershed moments of their storied, public lives.

Thank you for reading. Here is the NY Times article that covered the Schmeling-Stribling fight. The style of writing is of course in classic, early-20th Century sportwriter style.

Here is YouTube footage of Schmeling vs. Stribling. The final round begins around 9:30. The scene of Schmeling carrying Stribling to his corner is seen, as well.

Other sources included United Press newspaper reports, this book, this article, this book review, this book, this site, and WIkipedia.

*****Boxing fans: on the card in Cleveland the night of the Schmeling/Stribling fight was a George Pavlik of Cleveland. Anyone know if he was a relation of Kelly Pavlik?

Schmeling and Louis:

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 11:53 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

skatingtripods (Tuesday, January 21 2014 11:52 AM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)