General

General  General Archive

General Archive  Top Cleveland Sports Figures, By the Numbers - #14

Top Cleveland Sports Figures, By the Numbers - #14

This is one installment in a team effort by The Cleveland Fan, highlighting the top local sports figures by jersey number. Please weigh in with your thoughts on the Boards. And as David Letterman would say, “For entertainment purposes only; please, no wagering.”

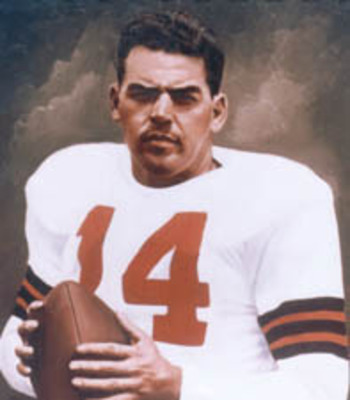

The #14 is one of the more storied digits in Cleveland Sports history. Both the Browns and the Indians have retired the number, the only number that shares that unique distinction. Unfortunately for Indians great Larry Doby, #14 adorned the jersey of one of the all-time greatest players in NFL history, Otto Graham. Doby actually deserves his own article, so I’m not going to rehash his remarkable career highlights here. Graham actually wore #60 for much of his career, but when the NFL standardized numbers in the manner we know today, Graham gave 60 to his good friend Bill Willis and took the only number in the teens that wasn’t already spoken for, #14.

When conducting my initial research for this article, I was blown away by Graham’s numbers and accomplishments. For starters, Graham played in a championship game every season as a professional; four in the AAFC and six in the NFL. He won seven of those games, a level of success not seen before that decade nor since. He made first-team All-Pro in nine of his ten seasons, making the 2nd team in 1950. He was the NFL MVP in 1951, 1953 and 1955. He was one of the four QB’s selected to the NFL 75th Anniversary team in 1994, and if he’s not on the 100th Anniversary team in 2019 it will be a crime. He’s still the NFL’s career leader in yards per attempt with an even 9.0. He was the Big 10 Player of the Year in both football and basketball in the same season. His career record as the Browns QB was a mind-boggling 114-20-4. That’s literally just scratching the surface of his remarkable sports resume. But these accomplishments are easily found by entering Graham’s name into Wikipedia or Google. I wanted to find a way to relate Graham to a new generation of Cleveland fans. Fans that know that Graham is one of the all-time greatest players in NFL history, but don’t have the same memories of watching him as our fathers and grandfathers did.

While racking my brain of how to pay homage to this legend of Cleveland sports, I came across the website OttoGraham.net. The site is run by Graham’s oldest son, Duey and provides Duey’s e-mail address for contact in case people have questions about Otto. I decided to take a shot and send Duey an e-mail, not really knowing if he’d have the time or inclination to respond. Less than 2 hrs later, I had a reply to my e-mail that included a contact # for Duey and a time to call and talk with him. I called Duey the next day, and we talked for about an hour and 45 min about Otto Graham’s playing and coaching career, and about what it was like to have Otto Graham as a father. Here are the highlights of that interview, lightly edited:

I asked Duey if he thinks Otto is properly appreciated by this generation of football fans:

We’ve been involved with the Madden video game; they’ve got a Legends Division now and they give every player a value, and Dad’s got the highest value of all the QBs. People are discovering him through that alone.

There’s always comparisons to somebody; they were comparing Dad and Flacco because they’re the only guys to lead their teams to the playoffs their first five years in the league. Dad or course did it six years, so if Flacco can do it again next year they’ll be talking about it again.

On Otto’s personality:

On Otto’s personality:

Dad was a jokester; LBJ was at the Redskins 1st preseason game which they lost 30-0 to the Colts. After the game, he was asked what he thought of the president being at the game, to which Dad jokingly replied “well if that’s the kind of luck he brings us, I’d rather he just stayed at home!” The headline the next day was “Otto Tells LBJ to Stay Home.”

Otto famously went to Northwestern on a full ride for basketball, and was talked into going out for the football team:

He had zero football scholarship offers. He had narrowed down the basketball scholarship offers between Northwestern and one of the Ivy League schools on the East Coast, and chose Northwestern because it was closer to home. So he went on a basketball scholarship, but the basketball coach was also an assistant football coach. He played in the intramural league for his fraternity and went undefeated, and were playing the championship game in the stadium. Northwestern's head football coach, Lynn "Pappy" Waldorf went to the game, Dad had a great game and his team won the championship, so Pappy invited him to come out for spring ball. He was going to play baseball, but came out for the spring game and ran for a bunch of yards and a couple of touchdowns and totally outshined their starter.

His nickname “OttoMatic” came from basketball; at one point he was scoring about a point a minute.

I asked Duey about Otto being the first Cleveland Brown, and what it meant to be the first:

Paul threw the ball a lot more than any other coach at the time; most of the coaches were more into running the ball, but they didn’t have a QB like Otto.

OSU was national champs in 1942, and Northwestern beat them in 1941 and 1943. So Paul remembered Dad, and Paul drove down to Chapel Hill when Dad was in the Navy to sign him. The Lions had drafted him in the first round in 1944, but never went down and followed up or anything, whereas Paul actually went down, showed an interest and signed him up.

I asked Duey if his Dad had a favorite play and he said not that he knew of, but did have a good story about the invention of the draw:

My Dad and Marion Motley actually accidentally invented the draw play. Dad was dropping back to pass, and the center stepped on his foot which tripped him. So as he’s dropping back, he’s losing his balance and basically running backward. On the way back, he saw Marion getting ready to block so he just stuffed the ball in his gut. Dad kept falling and all of the defensive lineman jumped on top of him, meanwhile Marion just stood there waiting as they all ran by and then took off running. By the next practice, Paul Brown had about four different draw plays drawn up.

On whether Otto changed any of Paul Brown’s plays that were sent in by messenger guards:

The only time Dad really changed one of Paul Brown’s plays was when Dub Jones had five TD’s in a game, and towards the end of that game Paul sent in a play to just run down the clock. Dad really wanted to get Dub his 6th TD, and called a post pattern for him that went for a TD. Dad jogged over to the sidelines and on the way by Paul just said “nice pass.”

I asked Duey what his Dad’s proudest athletic accomplishment was:

I asked Duey what his Dad’s proudest athletic accomplishment was:

The 1950 championship. He joked that his claim to fame was that it took Vince Lombardi to replace him as a head coach (of the Redskins), but there’s no doubt that 1950 championship was his proudest moment as a professional.

To play the Rams for the championship was nice, because they had vacated Cleveland of course. One thing people forget about that game is that after Groza kicked the field goal to put them ahead, there was still some time on the clock, really just enough time for a kickoff return. The Rams player ran it back, and the fans all came onto the field when the clock hit zero but the play was still in progress. He got to the end zone! He managed to find his way through all of the crowds and into the end zone. These days, with replay and everything, that might have ended up being a touchdown.

We got talking about the Super Bowl, and I remarked that I (like nearly all Browns fans) had been cheering for San Francisco, for obvious reasons:

You want a story about Art Modell? Dad was coaching the college all-star game in 1962 when Ernie Davis was coming out of Syracuse, and he was one of the all-stars. Dad had seen Ernie play at the Senior Bowl, and was blown away by the kid, so Dad was really expecting big things out of Ernie in the all-star game. I was one of the water boys at the game, and I remember Ernie always having an open sore on his elbow; it just never went away. Ernie was listless, he didn’t have anywhere near the energy he used to have. He was just a shadow of himself. They do a physical of all the all-stars, and that’s when they found the leukemia. As soon as that was found, Dad called up Paul Brown to tell him that Ernie was sick, and would have to leave camp.

Art Modell had just taken over the team and was demanding that Ernie play in that first game. Dad was trying to tell Paul that there was no way he could play, that he couldn’t even practice with the college all-stars and that putting him in a NFL game would just be terrible. Paul stuck to his guns and told Modell that he would not play Ernie Davis. Modell’s response? “Well, can you just let him run back a kickoff?” Paul of course replied that was the most dangerous part of the game, stood his ground and refused to play him. Paul allowed Ernie to dress for the first game of the year, but Art wanted him to play. Because Paul stood up to Art, that’s why he got fired. It took all season for him to let him go, but the relationship was never the same after that.

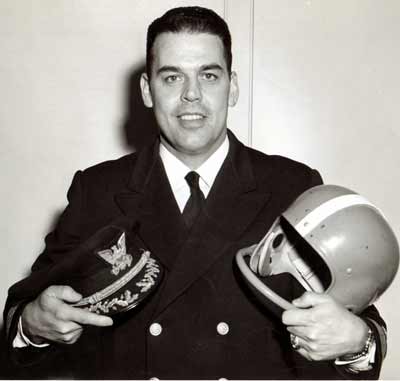

Since we were already on the topic of eccentric millionaires, I asked Duey about his Dad’s long-lasting friendship with George Steinbrenner:

It was George that talked Dad into going to the Coast Guard Academy. When George had his shipbuilding company in Cleveland he had a lot of dealings with the Coast Guard. The commander of the CG station at the time went on to become the Admiral at the CG academy. When the coach at the CG academy called it a career, George suggested that the Admiral call Otto Graham to see if he’d be interested in coaching at the CG. Then George called Dad up and suggested he coach at CG academy. So George talked Dad and Mom into hopping on a train and going up there and they spent three days up there. When they got on the train to come back, the first thing my Mom said was “thank God we’ll never have to see that place again.”

George stayed Dad’s friend forever. When Dad had his rectal cancer, George was the 2nd guy to come visit Dad in the hospital, right after Ted Williams.

I asked Duey if he knew what his Dad thought of Cleveland:

Dad loved Cleveland. There’s nothing not to like about Cleveland. We lived in Bay Village and Willoughby Hills. The only time I was popular in school was on career day when they had all of the dads come in to school.

I remarked on Otto’s remarkable durability, as he never missed a game in his 10-year career:

I remarked on Otto’s remarkable durability, as he never missed a game in his 10-year career:

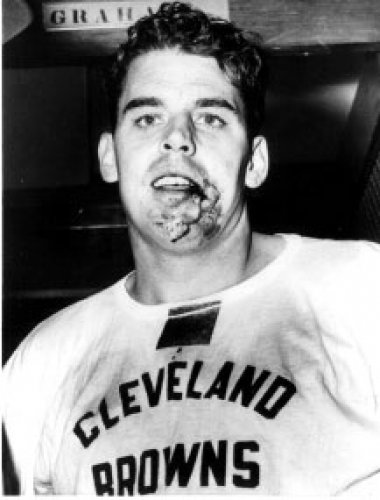

There were a couple of games during his career where he wasn’t supposed to play; the only one he didn’t start was his first one. Cliff Lewis, who was the backup, had been in training camp while Dad was at the all-star game. So the first preseason game, Paul Brown figured he had earned the start. Cliff Lewis actually threw the first TD pass for the Cleveland Browns. They had a trip where they went to the West Coast and played two games. They played the LA Dons on Thanksgiving Day, and then on Sunday they played the 49ers. Then they flew home and had a home game. During the Dons game Dad had gotten tackled hard and rolled up his knee, and they were supposed to play the 49ers a few days later. He sat in a salt bath for basically the next three days, but when they went to play the 49ers his leg was black, I mean the whole thing was black. So they taped him up and said “you’re not playing.”

Cliff was all warmed up and ready to play, but when they kicked off and the Browns got the ball, Dad jogged on to the field and that was that. Back in those days, this is how different things were, the 49ers coach told his players that if anyone hit Otto Graham and knocked him out of the game, that player would be off his team forever. So during that game, every time the defense broke through and tackled him they would almost gently lay him on the ground. That would NEVER happen now. Dad didn’t understand what was going on until afterwards one of the players on the 49ers who used to be on the Browns came up to him and told him about the coach’s orders. That’s class.

We got to talking about Cleveland’s other legendary #14, Larry Doby. Duey said that he couldn’t remember if his Dad knew Larry, but that the Browns were integrated before the Indians:

Marion Motley and Bill Willis came on before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball, and there were a lot of problems that ensued because of that. I remember when they went to Baltimore the one hotel wouldn’t let the black players stay. So Paul Brown said “well if they’re leaving, we’re leaving.” That was the end of that. When the Browns went down to Miami in 1946, Florida law prohibited black and white players from playing on the same field, so the Browns had to leave Motley and Willis behind. That didn’t sit well with anyone, and the black folks in Miami wouldn’t support the team and rightfully so. So Miami folded pretty quickly, and that’s when the Colts came into the league.

I asked how Otto decided to take up coaching after he retired:

The first year my Dad coached the college all-star game he was an assistant under Curly Lambeau. My Mom didn’t want him to coach; the pressure of being in the NFL as a player was bad enough and she thought when he was done playing that would be the end of it. But he talked her into letting him be an assistant coach at the ’57 game, and after watching how Lambeau ran the team, there was no doubt in his mind that he could coach. Paul Brown was so meticulous about everything, but the way Lambeau ran things was much more loose. So he came away from there knowing that he could coach anywhere he wanted to if he chose.

I asked about that final season in 1955, and how Paul Brown was able to coax Otto out of retirement:

My Dad was a man of his word. Dad had decided to retire after nine years, but he told Paul that if he didn’t manage to find anyone else to play QB, that he would come back. Well, Paul never looked all that hard. He did draft a QB but the kid had signed a contract up in Canada, and when the Browns drafted him the Canadian League went to court to fight it and the courts sided with the Canadian League. So Paul went back to Dad and said “you promised!” So Dad agreed to come back. Paul put a blank contract in front of him. Dad’s contract had been for $22,000, because he hadn’t been playing that great for the last few years, but Paul told him to just fill in what he wanted. Dad filled in $25,000. Paul kinda chucked, and said “I would have given you $30,000!” And Dad replied, “well that’s good, because I almost wrote in $20,000.”

Well, since Dad had kinda been there and done that by this point he wasn’t really in shape…these guys back then didn’t get in shape and exercise like they do now. That very first game, Dad wasn’t nervous or anything. Normally his pregame meal consisted of oranges and a Hershey bar because he couldn’t handle anything else. But this time he had a full breakfast, thinking he would just play and have a good time. Well, game time comes and Dad starts to get nervous. He ended up throwing up his breakfast in the locker room. Then he went out and just had a terrible game, going 0-something. Paul Brown took him out, benched him for the rest of the game. Dad learned his lesson, got refocused after that and the ended up winning a championship.

The nice thing about the way Dad went out was that he went out a champion, and was able to beat his two nemeses in those last two years, the Lions and Rams. He threw for two TD’s and ran for two more in that last game, and the year before ran for three more. He was in LA Stadium when Paul put in Ratterman for the last time, and he got a standing ovation from the LA fans. He jogged off the field and said “thanks coach.” Paul said “thank you, Otto” and that was it. That was the conversation between them. They talked a lot since of course, but were both professionals to the end.

We got to talking about what it was like growing up as Otto Graham’s kid, and what Otto was like as a Dad and not just as a player or coach:

We got to talking about what it was like growing up as Otto Graham’s kid, and what Otto was like as a Dad and not just as a player or coach:

My Dad was a very black and white kind of a guy; there was very little gray in his world. One year at Dad’s golf tournament we were walking behind a celebrity when a kid ran up and asked the celebrity for his autograph. The celebrity told the kid to f-off and the kid went away crying. My Dad started walking a little faster, caught up with the guy and told him to pack his stuff and get in his car and get out of there, NOW.

When Dad coached the Redskins, that third year I was an assistant equipment manager. During camp, the place had an 11:00 curfew, and that included me. But the place we were staying in was in a girls dorm, and with my room being in the basement I knew I could sneak in. So one night I was sneaking in about 15 min late, but I knew the coaches weren’t going to look in my room. But as I’m sneaking in, I hear a noise and look up and it’s Sonny Jurgensen sneaking out after curfew. He sees me, I see him, we both sized up the moment pretty quickly with it being the coaches kid and the starting QB sneaking around after curfew. He says that he’s going out for a couple of beers, and asks if I want to join him. I’m 20 years old, and the starting QB of the Redskins is asking if I want to go grab beers with him, what am I going to say, no? So we hop in his car and go off to a pub down the road. We’re sitting at a table and he’s getting all the co-eds dripping all over him, and I’m obviously enjoying that. But at around midnight the phone rings in the bar and it’s Sonny’s roommate; they’d had a 2nd bed check. Sonny was to report to the coach right that moment.

So we go back, and I park Sonny’s car for him which was cool because it was a nice Mercedes. So I’m peeking around the corner as Sonny is knocking on my Dad’s door, and I can see my Dad is mad. He asks Sonny where he was, and Sonny says he was out having a couple of beers, but that it was ok because Duey was with me! I step around the corner and my Dad sees me, I walk up and thank Sonny for throwing me under the bus as well. Dad is furious, and just tells us that this will be dealt with in the morning and slams the door. I didn’t sleep very well that night. I walked in to my Dad’s office the next morning, and Sonny was already standing there. Dad asked if we had anything to say for ourselves. Sonny said “nope” and I said “nope.” Dad looked at Sonny and said “$500 fine. Now get out of here.” Then Dad just looks at me and says “PACK!” One word, that’s it. So I got out of there, threw my stuff in my car and left. That’s a good example of how, for my Dad, things were black and white. No grays.

I asked Duey if there was anything else he wanted today’s Browns fans to know about his Dad, anything that we hadn’t talked about yet that he’d like to see included in the interview:

Dad played for the love of the game. When he played, players didn’t just play football, they had jobs in the offseason. Dad was an insurance salesman. Money didn’t have anything to do with it. Dad would have probably paid Paul Brown to play football. And he just hated to lose. He had a lot of confidence, and that lasted throughout his life. There’s a fine line between confidence and arrogance, and my Dad could always walk that tightrope. And I think the reason he was able to do it so well is because he didn’t take himself too seriously. He knew he was a guy getting paid to play a kid’s game.

Oh, and one throwaway comment about Otto’s longtime friend Bob Feller:

Dad would always joke with Bob Feller that the rarest thing out there was a picture of Bob without his signature on it.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 11:53 AM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)