General

General  General Archive

General Archive  Top Cleveland Sports Figures, By the Numbers- #29

Top Cleveland Sports Figures, By the Numbers- #29

This was originally supposed to be a two-part piece, with two intertwined athletes featured: #29, Hanford Dixon and #31, Frank Minnifield. Like Lennon and McCartney or Tango and Cash, you can’t talk about the Top Dawg without Mighty Minny.

McCartney or Tango and Cash, you can’t talk about the Top Dawg without Mighty Minny.

Certainly Dixon and Minnifield would have been worthy selections in this series. After all, they were one of the best cornerback tandems in NFL history, with seven Pro Bowls and three All-Pro selections between them. More than anyone else, they were responsible for the phenomenon that was the Dawg Pound. They’re iconic figures in the sports history of this city, and rightfully so.

Yet after some reflection (and about 1,000 words of a Dixon-Minnifield column that will probably never see the light of day) I decided to go another route.

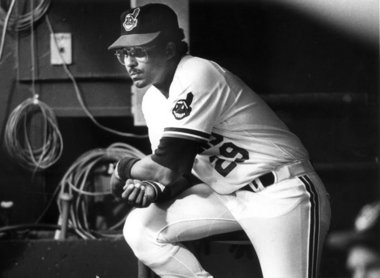

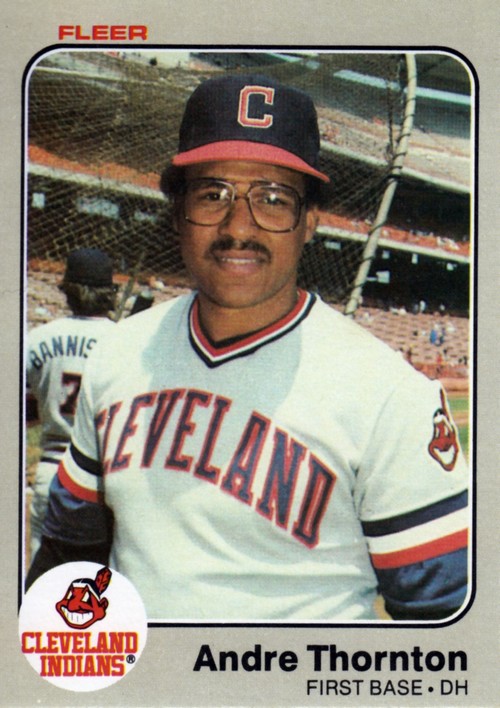

Andre Thornton wasn’t the most decorated man to wear the number 29 in Cleveland. His statistics weren’t overly impressive by the standards of a later day. He never distinguished himself in postseason play- not surprising considering he never played in the postseason. He played in an era that longtime Indians fans would like to forget- the 1970’s and ‘80s, when Cleveland was the Siberia of Major League Baseball. And he’s been lost in the wake of the conga line of sluggers- Belle, Thome, Ramirez, Hafner- that have worn a Tribe uniform in the three decades since.

But Andre Thornton deserves to be remembered, and not just because he was an excellent player in an era that for the Tribe was anything but. No one overcame tragedy more unthinkable to carve his place in the game. No one represented the Indians or Cleveland with more grace. Andre Thornton was a man's man, a true sportsman and a beacon of light at a time of pitch darkness for this city’s baseball club.

Andre Thornton took a long and circuitous road to Cleveland. Born in Alabama on August 13th, 1949, he grew up outside of Philadelphia, where he was a three-sport star as well as a renowned local pool shark. Indeed, Thornton’s hometown Phillies signed him right out of a pool hall as a free agent in 1967, just two weeks prior to his eighteenth birthday.

Thornton spent the next six years in the minors, going from the Phillies to the Braves and finally to the Cubs, where he made his major-league debut in July of 1973. He became a regular at first base the following season and in 1975 hit 18 home runs with 88 walks, displaying the powerful bat and keen eye at the plate that would become so familiar to Tribe fans years down the road. But, as usual on the North Side, the pitching staff was thin and early in the ’76 season Thornton was on the move again- this time to Montreal, for starting pitcher Steve Renko and utility man Larry Biitner.

The 1976 Expos were about as bad as it gets, going a nightmarish 55-107. Thornton didn’t exactly help matters, batting .191 in a part-time role. In the eyes of the Montreal brass, he wasn’t so much a solution as a continuation of the problem. With the team working on a trade to bring Tony Perez on board at first base, Thornton was eminently expendable. Besides the Expos, like the Cubs before them, needed pitching.

The Indians, meanwhile, needed hitting. The Tribe had hit a meager 85 home runs in 1976 and had just traded away the enigmatic George Hendrick, who had accounted for more than a quarter of that total. On December 10th, 1976, Cleveland sent 33-year old right-handed pitcher Jackie Brown to Montreal for Thornton. It would prove to be one of the best under-the-radar transactions in the history of the franchise.

Comfortably ensconced at first base with a team that was willing to commit to him, Thornton immediately proved his worth to jaded Tribe fans. In 1977 he belted 28 home runs, most on the team by far, and put together a .904 OPS. At 28 years old, after a nomadic ten-year journey through the game, Andre Thornton had finally found a home in Cleveland. Everything seemed to be looking up for the strapping slugger.

Comfortably ensconced at first base with a team that was willing to commit to him, Thornton immediately proved his worth to jaded Tribe fans. In 1977 he belted 28 home runs, most on the team by far, and put together a .904 OPS. At 28 years old, after a nomadic ten-year journey through the game, Andre Thornton had finally found a home in Cleveland. Everything seemed to be looking up for the strapping slugger.

On October 17th, 1977, two weeks after the completion of his first season with the Indians, Thornton, his wife Gertrude and his children Theresa and Andre Jr. were on their way to a wedding in Pennsylvania. The weather was bad, the roads were bad, and at some point Thornton lost control of the wheel. His van skidded across the icy PA Turnpike, flipped over and landed in a ditch. Thornton and his four-year old son lived. His wife and three-year old daughter did not.

As fans, it’s easy to envy the athletes we follow. After all, they have wealth and fame and the perks that go with both- and all from playing a game most of us played for free as kids. I don’t think anyone envied Andre Thornton after October 17th, 1977. As a young Indians fan growing up watching Thunder Thornton hit, I couldn’t imagine his tragedy. As a husband and a father, I don’t want to imagine it.

Thornton found solace in his religious faith and in his surviving son. He eventually remarried. And his dignity and faith in the face of overwhelming loss earned him respect everywhere he went. In 1979 he won the Roberto Clemente Award, given to the player who “best exemplifies the game of baseball, sportsmanship, community involvement and the individual’s contribution to his team.”

He also kept playing the game at a high level- a historical level for one day, at least. On April 22nd, 1978 at Fenway Park, Thornton hit for the cycle in a 13-4 Tribe romp over the Red Sox. Only one Indian- Travis Hafner in 2003- has done it since.

Over the next several years he became one of the most consistent power hitters in the American League. Except for 1980 (which he missed after suffering a knee injury in spring training) and the strike-shortened 1981 season, Thornton hit at least 17 home runs in every year from 1977 through ’86. He hit 20-plus homers six times and 30-plus homers three times. In the days prior to the distortion of power figures by steroids, those were pretty good numbers- especially with 81 games at Municipal Stadium, not exactly a bandbox.

In addition to being a powerful swinger, Thornton was also a disciplined one. He never struck out more than 93 times in a season, finished his career with 25 more walks than strikeouts and made up for a .254 lifetime BA with a .360 lifetime OBP. With his home-run capability and his penchant for drawing the walk, Thornton was the quintessential Moneyball player.

Thunder’s production and personality would have been welcome in any championship contender’s clubhouse. But he didn’t play for a contender. He played for the Indians, and in those days the words “Indians” and “contender” didn’t appear in the same sentence. Cleveland never finished better than fifth in the seven-team American League East, nor closer than 11.5 out during Thornton’s eleven seasons in the lineup.

The book on the Indians lineup was as easy to read as Dick and Jane. Thornton is the only man that can beat you: don’t let him. He probably got fewer pitches to hit than any other power hitter in baseball. Why pitch to Thunder when you could pitch to guys like Gorman Thomas and Carmen Castillo? His sharp eye wasn’t the only reason Thornton finished in the top five of the league in walks five times during his career.

than any other power hitter in baseball. Why pitch to Thunder when you could pitch to guys like Gorman Thomas and Carmen Castillo? His sharp eye wasn’t the only reason Thornton finished in the top five of the league in walks five times during his career.

The 1982 season was a typical one for Thornton and the Indians. After missing all of 1980 and hitting just .239 in ’81, Thunder came back with perhaps his best season: a .273 BA, .386 OBP, .870 OPS, 32 home runs, 116 RBI and a 109-81 walk-to-strikeout ratio. He made the All-Star team for the first time and won the Sporting News Comeback Player of the Year Award. But he didn’t win anything else. Even with Thornton the Tribe hit the second-fewest home runs in the AL and finished tied for last in the East with a 78-84 record, seventeen games off the pace.

Thornton could have complained. He could have tried to force his way out of Cleveland. He wouldn’t have been the first player to do so. Instead he kept his head up, kept whatever ill feelings he had to himself, and kept playing.

At the end of his time in Cleveland there should have been a note of thanks for his contributions. There should have been an Andre Thornton Day at the Stadium. There at least should have been a deadline-day deal to a contender. Instead Thornton simply rotted on the bench the entire 1987 season, a forgotten hero, as the Indians lost 101 games. After a decade of representing the club with consumate class, he deserved far better than what he got at the finish.

Eventually Thornton, who still lives in the area as a successful businessman, did receive the recognition that was his due. In 2007 he was elected to the Cleveland Indians Hall of Fame, an honor that was more than deserved. There have been better players and better sluggers for the Indians. There have been arguably better athletes to wear #29. But there was never a better Cleveland Indian in particular or Cleveland athlete in general, in terms of the way he carried himself and the way he represented the uniform and the city, than Andre Thornton.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Hikohadon (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:24 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)