General

General  General Archive

General Archive  Cleveland Sports Vault: Local Teen Begins Journey to the Baseball Hall of Fame

Cleveland Sports Vault: Local Teen Begins Journey to the Baseball Hall of Fame

What is your earliest childhood memory? Can you hearken back to when you were four years old? Three? I have a memory from November, 1963. I was 27 months old. I was sitting with my sister on the tiled family room floor, between our mother and the black and white television with the furniture legs and the rounded glass screen. Mom was ironing.

What is your earliest childhood memory? Can you hearken back to when you were four years old? Three? I have a memory from November, 1963. I was 27 months old. I was sitting with my sister on the tiled family room floor, between our mother and the black and white television with the furniture legs and the rounded glass screen. Mom was ironing.

Mom was glued to the TV. This happened several times in the 1960s; political unrest, civil rights demonstrations, and the exploits of the NASA space program drew Americans to their televisions in a similar manner to the events that caused citizens to huddle around radios a generation earlier.

On the TV in my earliest memory was the drama of the aftermath of the John F. Kennedy assassination. I very distinctly recall the funeral procession, in particular. The crowds, the horses, the large United States flag draped over what I’d one day learn was the president’s casket on that carriage. The heavy drama of that entire week beamed through every TV in the country.

Eh- maybe I just remember knowing about all that, at an early age. Who really knows for sure. Either way, for me, there is personal intrinsic value in that story.

Other very early memories I have are of summertime parades. I used to love those. The fire trucks and police cars turned their sirens and lights on- what little boy wouldn’t love that? The marching war veterans commanded my attention, as well. I definitely recall being told that the oldest of those had fought in the Spanish-American War.

attention, as well. I definitely recall being told that the oldest of those had fought in the Spanish-American War.

Wow- I observed men who had seen battle in a war fought in the Nineteenth Century. Wouldn’t it be terrific to have the opportunity to have a conversation with them today? What was it like? Did they know any stories involving Teddy Roosevelt? It might be best to just be quiet and let them reminisce.

One of the great things about baseball is that while it was the king of American sports in a bygone era, legions of writers dutifully recorded the game. Sure, there was a protective filter that was honored by beat reporters, men who lived with the ballplayers for most of the year. But in addition to descriptions of performances and results, we have engaging details of the lives and times of the boys and men who played the game.

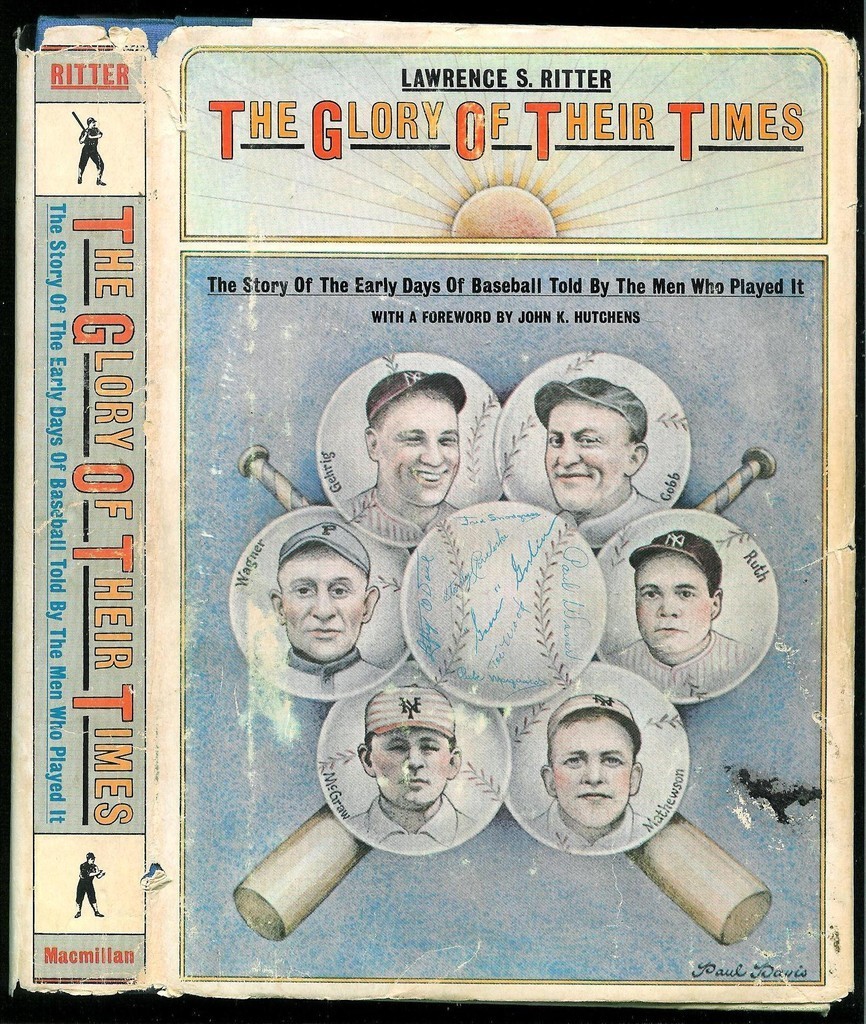

There was a 1966 project that broke new ground with its interviewing style. Lawrence S. Ritter, having tracked down men who’d played baseball 40-60 years prior, simply let the ballplayers talk. They were given free rein to go in any direction they liked, and to speak about whatever they wanted.

The project's fascinating compilation is the seminal The Glory of Their Times, The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It. It is a must-own for baseball fans. To read what are basically transcripts of now-100-year-old tales is highly compelling.

One thing that strikes the reader is how interwoven the city of Cleveland has been through the fabric of baseball history. It seems every other account involves a Clevelander, a Cleveland player, or at least an indirect connection to the town.

I thought it would be fun to look at some of the book’s first chapter. If you have not read the book, and you think you might enjoy it after finishing this account, please pick it up- you’ll not be disappointed.

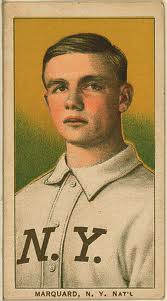

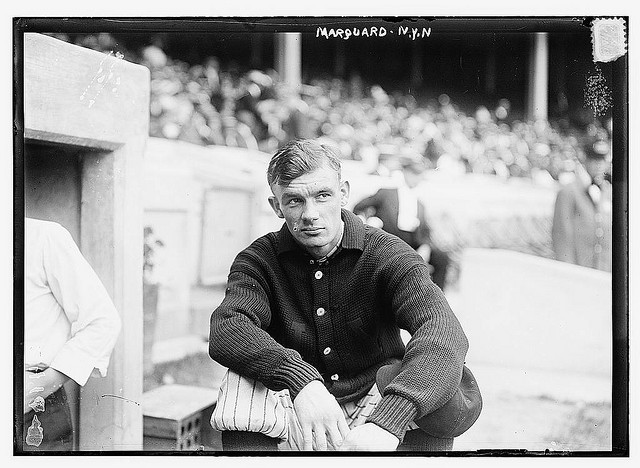

Chapter One - Rube Marquard

Marquard explains that he grew up in Cleveland, as the son of the city’s Chief Engineer. His father’s firm requirement for young Richard was that he get a good education. And to Dad, baseball could only interfere with that. The boy’s grandfather would even speak highly of a baseball career, to no avail.

Marquard explains that he grew up in Cleveland, as the son of the city’s Chief Engineer. His father’s firm requirement for young Richard was that he get a good education. And to Dad, baseball could only interfere with that. The boy’s grandfather would even speak highly of a baseball career, to no avail.

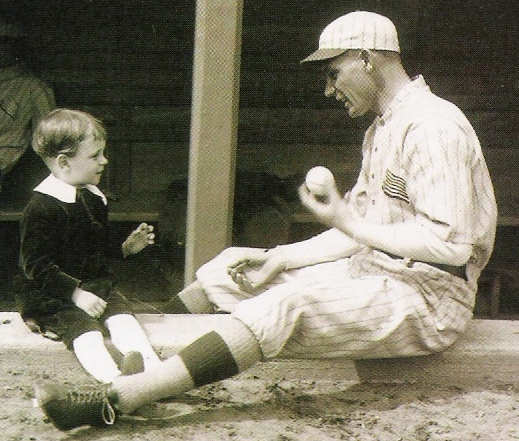

Young Richard was tall for his age, and he played ball with the older kids. As he grew into his teenage years, he became the batboy for the Cleveland ballclub. They were known as the Bronchos, and then the Naps (in honor of the great Napoleon Lajoie). He carried bats for Lajoie, Elmer Flick, Terry Turner and the other players. After the season was over, the team would barnstorm around Cleveland and Marquard continued to serve as their batboy.

He, too, wanted to become a big league ballplayer. He was a lefty pitcher with a good arm.

One of Marquard’s (older) friends caught on with a minor league team in Iowa, and told him to come and try out for the team. He apparently thought Marquard was older than the fifteen or sixteen he actually was. Marquard was ready- but he didn’t have any money with which to get there. He couldn’t ask his father…

A telegram arrived at the Marquard home in Cleveland. The Waterloo manager was offering to reimburse Marquard for transportation, if he could first earn a spot on the team. Marquard wrote back with a long appeal for a cash advance for the trip west. Every day, the boy made sure he retrieved the mail, since if his father saw correspondence from a baseball club, young Richard would have a serious problem.

But no reply came. Eventually, the impatient kid left home, under false pretenses. It was his first time ever away from home. It took five full days to get to Waterloo. He rode freight trains, slept under the stars, and hitched rides. When he arrived in town, the depot stationmaster (there is a photo of the station in the book) grabbed him, and was revolted by how filthy he was. Marquard had to explain how he was not a vagrant- he was a ballplayer. He could prove it, with the help of his buddy on the team.

help of his buddy on the team.

The manager of the Waterloo club was not his friend. He told Marquard he would pitch the next day, but accomodations and clean clothes were his problem to worry about. Food, as well. And he’d get paid after the game. Marquard was completely exhausted when he pitched, yet he won a 6-1 game.

It became clear to Marquard that the manager was going to take advantage of him for as long as he could- no contract would be forthcoming. The dejected teenager returned to the depot for the trip home to Cleveland.

The first leg of the trip led him to Chicago, where he came upon a fire house. Nobody was around, so he sat down and nodded off near a warm big-bellied stove. The firemen returned from a run, and woke him up. He told his story- that he was a ballplayer from the Cleveland sandlots, but they did not believe him. Taking a liking to him, they pooled some money together to send him home. Richard Marquard declared that one day, when he made the big leagues, he would be back.

Once he got home, the Cleveland ballclub made him an offer. Marquard was wary- he was not going to be taken advantage of again, and oh-by-the-way they had complicated matters by alarming his father. The offer they made was no better than what the kid was earning at the ice cream company where he worked (plus, that job included all the ice cream he could eat…). He did not sign with Cleveland.

In a fortuitous turn, Marquard met Charlie Carr, a Clevelander who managed the Indianapolis ballclub. Carr asked him to sign. Marquard named his price, and Carr agreed.

Richard Marquard’s father listened to the details of the contract… and disowned his son.

The pitcher was noted by a baseball writer as having a resemblance to another great left handed pitcher, Rube Waddell. The nickname “Rube” stuck. He began to have success as a minor league ballplayer.

Cleveland again came calling, but Rube Marquard was done with them…

Cleveland again came calling, but Rube Marquard was done with them…

Late in the 1907 season, the big leagues had an off day, and the teams’ representatives descended upon Columbus, Ohio to watch Marquard pitch. He threw a perfect game that day, and every one of the big league teams bid on him. Cleveland bid $10,500. The New York Giants’ bid of $11,000 was the winner; that was the highest price ever paid for a player, to date.

In the early portion of the 1909 season, the Giants had a road trip to Chicago. The nineteen year old pitcher couldn’t wait. When they arrived, he proceeded directly to the old firehouse where he’d showed up a few years earlier. After a few moment, the firemen remembered him- and so began several years of reunions. The firemen would gather the kids from the neighborhood and have them meet Rube. It was a thrill for everyone, including the pitcher.

Years later, an elderly visitor requested to see Rube Marquard, when he was with the Brooklyn Dodgers. It was his father. They reconciled, and spent considerable time with each other in New York.

Rube Marquard was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971. There is some debate over the level of truth to some of his personal accounts… Personally, I do not expend energy on such concerns. Really, who cares? It’s baseball - there is considerable intrinsic worth in the memories of an old ballplayer from days gone by.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

mattvan1 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:19 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)