General

General  General Archive

General Archive  Top Cleveland Sports Figures, By the Numbers - #36

Top Cleveland Sports Figures, By the Numbers - #36

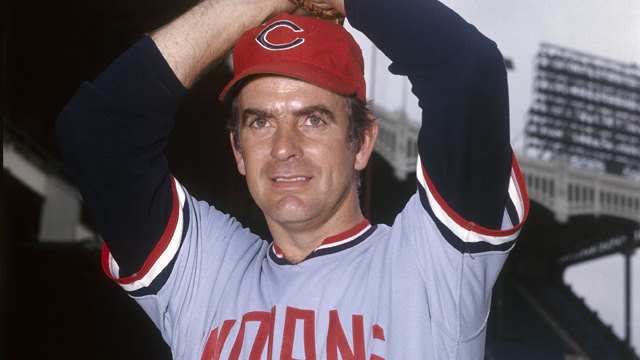

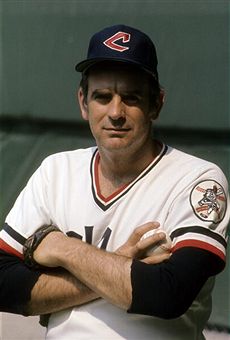

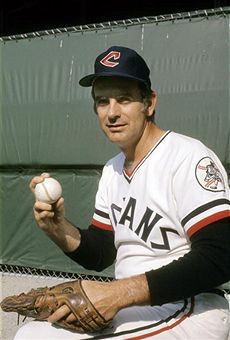

This is one installment in a team effort by The Cleveland Fan, highlighting the top local sports figures by jersey number. Please weigh in with your thoughts, in the Boards. As David Letterman would say, “For entertainment purposes only; please, no wagering.” Gaylord Perry pitched less than four of his 22 big league seasons for the Indians, but while he was here, he was the best player in town, and that’s more than enough to make him the best ever #36 in Cleveland sports history. As we’ll detail later, the competition for top honors at #36 was long on mediocrity and short on stardom, but Perry’s record in Cleveland would stand up well regardless of the number on his back.

Gaylord Perry pitched less than four of his 22 big league seasons for the Indians, but while he was here, he was the best player in town, and that’s more than enough to make him the best ever #36 in Cleveland sports history. As we’ll detail later, the competition for top honors at #36 was long on mediocrity and short on stardom, but Perry’s record in Cleveland would stand up well regardless of the number on his back.

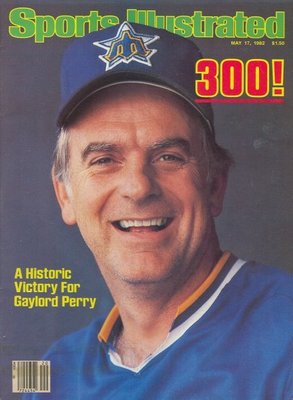

As a 300-game winner and a Hall of Famer, Gaylord Perry’s place in baseball history would be assured even without the controversies that marked his career almost from the time he became a regular in the rotation of the San Francisco Giants in the mid-60’s. Perry will always be best known as the master of the spitter...or the greaseball pitch. For two decades, Perry threw the wet one, a pitch that baffled hitters, enraged opposing managers, confused umpires and inspired various rules changes and interpretations by league officials.

In Cleveland, Perry won the first of his two Cy Young Awards, but he also earned a ticket out of town when he proved unable to coexist with manager Frank Robinson in 1975. Perry was the epitome of durability, his 303 career complete games perhaps more impressive than his 314 victories. He played for eight different teams, but the majority of his career was with the Giants, for ten years, and with the Indians and Rangers for four years each.

--- Gaylord Perry grew up on a North Carolina farm, the son of a semi-pro baseball player. He and his older brother Jim were both star athletes in high school, and Jim preceded Gaylord into professional baseball. Jim signed with the Indians organization in 1956, and went on to amass 215 major league victories, mostly with Minnesota. Gaylord was all-state as a two-way end in football, and he turned down many college basketball scholarships after averaging almost 30 points and 20 rebounds in his three-year high school hoops career.

Gaylord Perry grew up on a North Carolina farm, the son of a semi-pro baseball player. He and his older brother Jim were both star athletes in high school, and Jim preceded Gaylord into professional baseball. Jim signed with the Indians organization in 1956, and went on to amass 215 major league victories, mostly with Minnesota. Gaylord was all-state as a two-way end in football, and he turned down many college basketball scholarships after averaging almost 30 points and 20 rebounds in his three-year high school hoops career.

Perry came up through the Giants farm system, and after four years in the minors, caught on with the Giants major league staff for the 1962 season. He moved up and down to AAA during the 1962 and 1963 seasons, but didn’t put it all together until the team traded for a pitcher named Bob Shaw after the ‘63 campaign. Shaw taught Gaylord Perry how to throw a spitter, and a Hall of Fame career took off.

Perry went 12-11 with the Giants in 1964, and after a down year in ‘’65 (8-12), he would win at least 15 games for ten consecutive seasons, counting his time in Cleveland, with three 20+ win seasons in that span. And the more he won, the louder the complaints about his spitter became.

Acquitting the Spitter

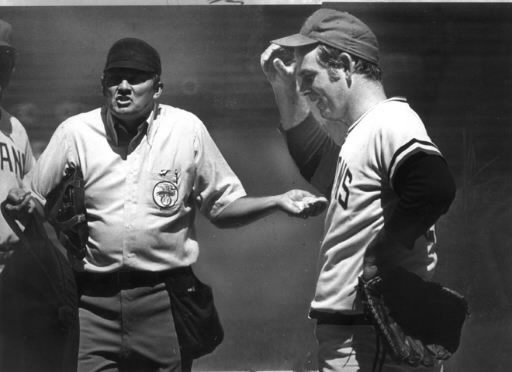

Although Perry would admit, on and off, that he threw the illegal pitch, going so far as to publish a memoir called Me and the Spitter; An Autobigraphical Confession in the middle of his career in 1974, he was never so much as ejected from a game for throwing it until he was 44 years old, and in his 21st season in the majors. Many other pitchers threw spitters in those years, but nobody else seemed to have as much fun with it, or garner as much notoriety for it. The spitter was officially illegal in baseball, and had been since the 20’s, but in the 60’s there was a movement to legalize it, mostly because the rule was unenforceable, as pitchers were allowed to lick their fingers on the mound, and no one could prove they weren’t wiping them off. Perry was challenged early and often by opposing managers, although his official stance, at least until the book came out, was that he was doing nothing illegal. Even after the book, Perry insisted that his rule-breaking was all in the past, and he no longer used the pitch. Not a soul believed it.

The spitter was officially illegal in baseball, and had been since the 20’s, but in the 60’s there was a movement to legalize it, mostly because the rule was unenforceable, as pitchers were allowed to lick their fingers on the mound, and no one could prove they weren’t wiping them off. Perry was challenged early and often by opposing managers, although his official stance, at least until the book came out, was that he was doing nothing illegal. Even after the book, Perry insisted that his rule-breaking was all in the past, and he no longer used the pitch. Not a soul believed it.

After the 1967 season, and a multitude of complaints about Gaylord Perry, the league outlawed pitchers going to the mouth on the mound. This just served to force pitchers to use something other than spit on the baseball, which they did. In his autobiography, Perry said "I reckon I tried everything on the old apple but salt and pepper and chocolate sauce topping.”  Managers tried everything to get umpires and the league to enforce their own rules. Ralph Houk ran up behind Perry on the mound once, ripped Perry’s hat off and threw it to the ground and kicked it. Perry was constantly being inspected and hounded by managers. Billy Martin once ordered his pitchers to throw nothing but spitters, as a way to draw attention to the refusal of umpires to enforce the rules. Opposing team management complained repeatedly to league officials, who would periodically order new, revised interpretations of the rules...all because of the flap over Gaylord Perry.

Managers tried everything to get umpires and the league to enforce their own rules. Ralph Houk ran up behind Perry on the mound once, ripped Perry’s hat off and threw it to the ground and kicked it. Perry was constantly being inspected and hounded by managers. Billy Martin once ordered his pitchers to throw nothing but spitters, as a way to draw attention to the refusal of umpires to enforce the rules. Opposing team management complained repeatedly to league officials, who would periodically order new, revised interpretations of the rules...all because of the flap over Gaylord Perry.

The umpires often ended up defending Perry, after time and again inspecting him and finding nothing punishable. For his part, Perry was amused by the distraction he was causing hitters, giving them one more thing to think about on every pitch.

Finally, in August of 1982, an umpire busted Perry holding a ball covered with Vaseline, and he was ejected from the game, as this article details, after over 5,000 major league innings pitched. Perry left the field without protesting the decision, I guess figuring it was about time.

On the Lakefront

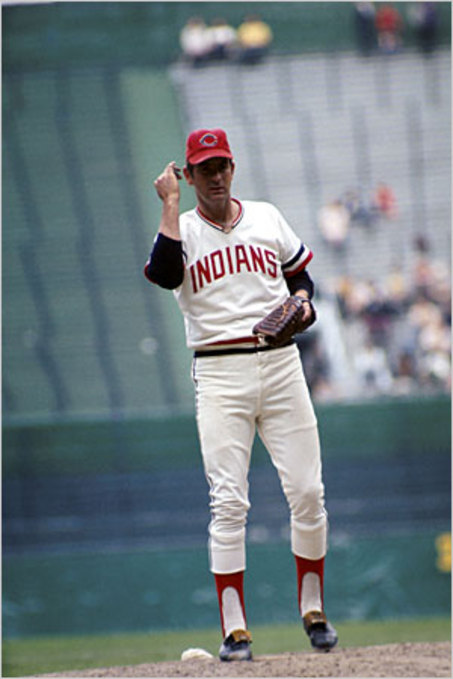

The Giants were an aging team trying to get younger when they traded Gaylord Perry to the Indians before the 1972 season for Sam McDowell. I recall the deal being generally unpopular in Cleveland at the time, despite Perry’s track record. (It certainly wasn’t popular with this Sudden Sam fan, although McDowell would win just 11 games with SF in a season and a half.) From 1972 until he was traded in June of 1975, Perry went 70-57 with a 2.71 ERA for an Indians team that never played .500 baseball while he was here. In 1972, he won the Cy Young Award for his 24-16 season with the Tribe, an honor not bestowed on another Indians pitcher for another 35 years. Perry led the American League in victories and complete games that season, making the All-Star team, and finishing 6th in the MVP balloting.

From 1972 until he was traded in June of 1975, Perry went 70-57 with a 2.71 ERA for an Indians team that never played .500 baseball while he was here. In 1972, he won the Cy Young Award for his 24-16 season with the Tribe, an honor not bestowed on another Indians pitcher for another 35 years. Perry led the American League in victories and complete games that season, making the All-Star team, and finishing 6th in the MVP balloting.

In 1974, Perry lost his first start, but then put together an incredible streak of wins in 15 consecutive decisions over 17 starts, one win short of the league record. On July 3 of that year Perry stood at 15-1, with a 1.31 ERA. All 15 wins in the streak were complete games for Perry, as was the game he finally lost, a 4-3 decision to Oakland in 10 innings. He faded in the second half, finishing 21-13, but still had a 2.51 ERA for the season.

Perry authored 17 shutouts in less than three and a half seasons in Cleveland, and pitched 96 complete games in that span. After three very good seasons, though, Gaylord Perry and the Cleveland Indians were about to become estranged.

“Some Superstar”

Perry was not known for being a great teammate. He angered players on his own side with several of the eight organizations he played for, by complaining publicly about the defense being played behind him. He would occasionally lobby the official scorer to change hits charged against him to errors on his teammates.  In Cleveland, Perry was so displeased with the play of center-fielder George Hendrick, that he asked manager Ken Aspromonte not to play him in Perry’s starts. Hendrick was angered by the criticism, and more than once refused to play at all, leaving the ballpark if he arrived and saw his name in the same lineup as Perry.

In Cleveland, Perry was so displeased with the play of center-fielder George Hendrick, that he asked manager Ken Aspromonte not to play him in Perry’s starts. Hendrick was angered by the criticism, and more than once refused to play at all, leaving the ballpark if he arrived and saw his name in the same lineup as Perry.

And of course Perry’s unwillingness to get along with new manager Frank Robinson in 1975 is well known here in Cleveland. On the day Robinson was acquired by the Indians in September of 1974, and before the aging slugger was named manager of the team, Perry demanded that he be paid one dollar more than Robinson’s salary of $173,500.

The animosity from Perry surfaced again early in spring training of 1975, Robinson’s historic first season at the helm of the Tribe. He refused to comply with Robinson’s running regimen, which had pitchers running foul line to foul line instead of the traditional sprints that Perry preferred. “I’m nobody’s slave....I’m not going to let some superstar who never pitched a game in his life tell me how to get ready to pitch,” said Perry at the time.

Perry also ripped the new manager in public for his decision to insert rookie pitcher Dennis Eckersley in the late innings of a spring training game as “as stupid and unfair a thing as I’ve ever seen”. Perry’s loud and frequent complaints about Robinson to the media, including occasional demands to be traded if things didn’t change, eventually resulted in the team trading him to the Rangers in the middle of June of Robinson’s first season.

Workhorse - Last of a Dying Breed Gaylord Perry liked to finish what he started, and his career was ending just as the era of the relief pitcher was beginning in major league baseball. In today’s game, an “innings eater” is a guy who can gut it out for 200 innings a season. Last year, Justin Verlander led the AL in innings pitched with 238.1, and in complete games with 6.

Gaylord Perry liked to finish what he started, and his career was ending just as the era of the relief pitcher was beginning in major league baseball. In today’s game, an “innings eater” is a guy who can gut it out for 200 innings a season. Last year, Justin Verlander led the AL in innings pitched with 238.1, and in complete games with 6.

In Perry’s Cy Young Award winning season of 1972, he pitched 343 innings for the Indians .It has been 35 years since an AL pitcher has gone even 300 innings. Baltimore’s Jim Palmer pitched 319 in 1977, and no one in either league has done it since Steve Carlton went 304 innings in 1980 for the Cardinals.

Even more astounding by today’s standards are Perry’s complete game numbers, especially for his time in Cleveland. In 1972 and 1973, he posted back-to-back seasons of 29 complete games, to lead the AL both years. In the 40 years since, only Catfish Hunter (30 in 1975) has had more, and with the advent of the 6-inning “quality start”, no one has had more than 15 in the last 25 years. No pitcher in the last 45 years has more career complete games than Perry’s 303, and it’s a safe bet no one in the next 45 will approach that number either.

Too Good to Check

There’s one other Gaylord Perry tale that must be told, and it’s one of those stories that might not even be true, but in the end...who cares?

As legend has it, Giants manager Alvin Dark once suggested that “they’ll put a man on the moon” before Gaylord Perry hits a home run. Then on June 20, 1969, within minutes of the Apollo 11 lunar landing, Perry hit his first ever major league homer. The date, if not the exact time, of the Perry homer (the first of 6 career dingers) is beyond dispute. What cannot be proven beyond doubt is the earlier statement by Dark (or someone else), which relies on a few inconsistent versions of the tale. As you might imagine, Snopes.com has weighed in on the veracity of the story, and has not reached a definitive conclusion.

---

Other Cleveland #36’s

To be honest, Gaylord didn’t have a lot of competition for top honors at #36 among Cleveland athletes. The list of memorable Browns players to wear the number begins and ends with Marion Motley, who wore #36 for his last two seasons in Cleveland in 1952 and ‘53. And Cavs records show that just one player in their history, Omri Casspi, has worn the number. They were apparently saving it till they got a guy from Israel.

There would be a treasure trove of Ohio State linebackers to talk about at #36...like Tom Cousineau, Bruce Elia, Marcus Marek, Chris Spielman, and Brian Rolle...if we were considering Buckeyes for this series. But we’re not...so I won’t mention them.

As far as the Indians go, we could put together an all-time “Bullpen from Hell” with the relief pitching retreads and rejects to have worn #36 for the Wahoos over the years. I did learn something I never knew before in researching this number for the Tribe...that the great Hall of Fame manager Dick Williams played about half a season for the Indians in 1957...and he wore #36. So did Sam Jones and Joe Frazier, for that matter....but not the Sam Jones and Joe Frazier that matter.  The best I could come up with as a runner-up to Gaylord as a Cleveland Indians #36 is Rick Waits, the left-handed starter who won 74 games for the Tribe from 1975 to 1983. Waits was never better in an Indians uniform than on April 7, 1979, when I froze my butt off along with 47,000 friends, watching him pitch a one-hit shutout of the Red Sox in the home opener. Incidentally, the probable reason Waits was wearing #36 in Cleveland was that he was acquired midway through the 1975 season in a trade for...Gaylord Perry.

The best I could come up with as a runner-up to Gaylord as a Cleveland Indians #36 is Rick Waits, the left-handed starter who won 74 games for the Tribe from 1975 to 1983. Waits was never better in an Indians uniform than on April 7, 1979, when I froze my butt off along with 47,000 friends, watching him pitch a one-hit shutout of the Red Sox in the home opener. Incidentally, the probable reason Waits was wearing #36 in Cleveland was that he was acquired midway through the 1975 season in a trade for...Gaylord Perry.

---

on Twitter at @dwismar

---

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

googleeph2 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 9:36 AM) - 2015 Recruiting

furls (Tuesday, January 21 2014 6:57 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - Movies coming out

HoodooMan (Monday, January 20 2014 9:34 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

OldDawg (Sunday, January 19 2014 6:48 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)