General

General  General Archive

General Archive  Mickey Mantle: 'So Gifted, So Flawed, So Beautiful'

Mickey Mantle: 'So Gifted, So Flawed, So Beautiful'

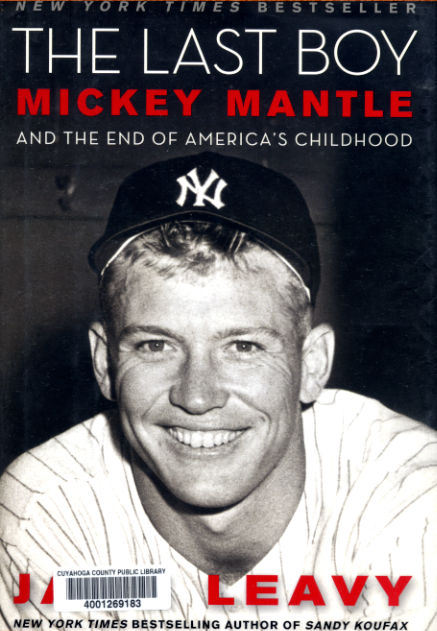

Of all the books written about sport, perhaps none is as definitive as “The Last Boy: Mickey Mantle and the End of America’s Childhood,” wherein author Jane Leavy explores the heights — and depths — of one of the most acclaimed baseball stars of the 20th century.

Of all the books written about sport, perhaps none is as definitive as “The Last Boy: Mickey Mantle and the End of America’s Childhood,” wherein author Jane Leavy explores the heights — and depths — of one of the most acclaimed baseball stars of the 20th century.

For Cleveland Indians fans, it’s a blast from the past, recounting days of yore when baseball was front-and-center in the nation’s conscience, when ballplayers were still just overgrown kids who played the game for fun.

“Far more than his contemporaries in center field, Willie and The Duke, Mantle fit the classical definition of a tragic hero — he was so gifted, so flawed, so damaged, so beautiful,” Leavy writes in the preface. She should know: she interviewed more than 500 people for the book, almost all of whom had first-hand knowledge of the life and legend of Mickey Mantle.

An admitted super-fan, Leavy also interviewed The Mick himself, at length, in the spring of 1983 at an Atlantic City hotel for the Washington Post — during which time he attempted to lure her to his room. When she wouldn’t comply, he simply passed out in her lap. After she and a waitress deposited him in a nearby elevator, she “went up to my room and cried.”

Although Leavy goes into great detail about Mantle’s life off the diamond (most of which is hard to read for fans like me) there’s plenty here for the baseball enthusiast — practically a vignette on every page, including his first home run as a member of the Yankees, in a spring training game against USC’s varsity in 1951. The fence was 439 feet where the ball went out of the park. Future NFL All-Pro Frank Gifford was practicing with the football team on an adjacent field; his quote:

“It went over the fence and into the middle of the football field where we were playing, which was probably another 40, 50 yards. The ball came banging into the huddle. It bounced and hit my foot. I said, ‘Who the hell hit that?’ Somebody said, ‘Some kid named Mickey.’”

Estimates of the distance on that particular ball range from 551 to 660 feet, “depending on whose diagrams, digital readouts…Google Earth satellite imagery…and trajectories you consult,” Leavy writes.

Younger fans who didn’t see Mantle play tend to look at his lifetime statistics as a measure of his glory. But his power and beauty is lost in the numbers. He almost became the first player to hit a ball out of old Yankee Stadium (hitting the right-field upper-deck façade 118 feet off the ground, 370 feet from the plate) in 1963. Mathematicians claimed that, had it not hit the façade, it would have traveled between 636 and 734 feet, depending on whether it was still rising or had reached its apogee. During his career, The Mick hit homers completely out of Tiger/Briggs Stadium, Comiskey Park, Griffith Stadium, Connie Mack Stadium and Busch Stadium.

Former Baltimore and Cleveland first baseman Boog Powell — who sculpted some towering homers himself — describes the sound of the ball coming off Mantle’s bat: “With your back turned, you knew it was him. It was a ring. It was more like a musical note.” And when Mickey hit that ball out of Briggs Stadium, Detroit manager Bucky Harris said, “Mmm, mmm, that would bring tears to the eyes of a rocking horse.”

Leavy writes: “After watching Mantle hit a blistering home run off ‘Sudden’ Sam McDowell in 1968, Yankee pitcher Stan Bahnsen asked the batboy if he could inspect the wood for bruises. ‘There were three or four seam marks in the barrel a quarter of an inch deep,’ he said. ‘Those seam marks were buried!’”

Before he injured himself his rookie year, Mantle was timed in 3.1 seconds from the left-handed batter’s box to first base. That’s almost 30 feet per second, equivalent to a 10.1 100-yard dash.

The book tells of his interesting relationship with Casey Stengel, his alcohol-fueled friendships with Billy Martin and Whitey Ford, and his non-relationship with devoted wife Merlyn and sons Mickey Jr., David, Billy and Danny — none of which enrich his legacy.

“He thought no one ever loved him,” Merlyn told Leavy.

But he was more emotional than he ever showed to those outside his immediate sphere. “He cried when a dying child was placed in his arms outside the clubhouse, and he cried when he failed,” Leavy writes, adding that teammate Hank Bauer told her, “One day he strikes out four times and goes back to the clubhouse, and he’s crying.”

But there are laughs, too. Plenty of them.

“They staged water-gun battles in the locker room and took aim at unsuspecting female noncombatants standing on the ticket line from the safety of the clubhouse,” Leavy writes. “‘The Yankee clubhouse was, like, below street level,’ Mantle told me. ‘We had windows, like where people are walking along. Girls used to come stand there, and we used to shoot water guns up in their puss. We could see ‘em kind of flinch. They’d be looking around trying to figure out where the fuck that water is coming from.’”

Leavy goes into great detail about the numerous leg injuries Mantle suffered that were much worse than the public ever realized. By the end of his career, his right leg consisted of flesh and bone and not much else. The femur rode directly atop the tibia, bone on bone.

Part Four of the book, which details his life after the Yankees, begins on June 8, 1969 — Mickey Mantle Day at Yankee Stadium, two months after he announced his retirement. Leavy recalls his failed business ventures, his realization that he lacked any real-world skills or specialized knowledge to be successful after baseball, and his utter discontent with the old-timers days, card signings, banquet keynotes and public events that played on his fame.

Finally, the author brings all the tales of injuries, tape-measure homers, overindulgence and long nights in bars together with a very detailed expository of The Mick’s last days, including his last press conference where he stated:

“God gave me a great body and an ability to play baseball. God gave me everything, and I just…pffttt!”

It’s great summer reading, and heartily recommended.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

Hikohadon (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:24 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)