General

General  General Archive

General Archive  The Worst Years In Cleveland Sports - 1991

The Worst Years In Cleveland Sports - 1991

The times were changing in Cleveland as the ‘90s went into full swing. The Society Center was completed, making the Terminal Tower, once the second-tallest building in the world, only the second-tallest building in town. The Flats continued its transformation from a graveyard of the old economy to its new incarnation- the Midwest’s largest manufacturer of drunk, horny people. The Gateway Project had been successfully secured, with construction of the downtown ballpark and arena set for early 1992. And, unbeknownst to all but a few, the Browns entered the final extremis of their original existence in the city. It was truly a year of transition in Cleveland.

It was also a year of losing- lots, and lots, of losing.

Browns: 6-10, 3rd AFC Central

Bill Belichick’s first season as coach resulted in a notable improvement from the disastrous 1990 campaign, when the Browns lost a club-record 13 games and lost by gaudy scores like 42-0, 35-0, 34-0, 34-13, 30-13, and 58-14. Cleveland doubled its win total in ’91, albeit from a paltry three to a somewhat less-paltry six. Belichick’s clever defensive schemes paid immediate dividends, as the team’s points allowed dove to 298 from a league-high 462 the previous season. Bernie Kosar, playing his last uninjured, uninterrupted season, had his best year since 1987, throwing for 3,487 yards and eighteen touchdowns against just nine interceptions. Leroy Hoard caught nine of the scoring passes. Best of all, Eric Metcalf ran the ball just thirty times, as Belichick hadn’t yet hit on the brilliant idea of using the little scat-back as his primary ball-carrier.

Incidentally, Belichick’s first win as a head coach was a 20-0 whitewash of the Patriots at Foxboro.

Despite the visible progress on the field, the season proved immensely frustrating at many times. Cleveland lost seven times by a touchdown or less, including a three-game mid-season stretch in which they had a game-winning field goal blocked in a loss at Cincinnati, blew a 23-0 lead in a loss to the Eagles, and lost at Houston on a Sunday Night when the Oilers scored with under ten seconds to play. With two weeks left in the season, the Browns lost to the Oilers again when Matt Stover slipped on the snowy Municipal Stadium dirt and shanked an 18-yard game-tying field goal attempt. Unlike the previous year, Cleveland didn’t get blown off the field in 1991; the only team that routed the Browns was the 14-2 Redskins, 42-17 at RFK, and that was a four-point game going into the fourth quarter, where Ricky Ervins and Washington’s great offensive line broke things open. To paraphrase Bill Walsh speaking of Steve DeBerg, the 1991 Browns played just well enough to get themselves beat.

Still, this was to be the closest thing to a honeymoon season Belichick had in Cleveland. Already having burned his bridges with the local media, he began to burn them with the fans when he took Tommy Vardell in the first round of the ’92 draft and started jettisoning popular veterans the following summer.

Cavaliers: 33-49, 6th Central

For all intents and purposes, the Cavaliers’ 1990-91 season ended in Atlanta on the last day of November. That night, Mark Price collided with a rolling sign attached to the scorer’s table in the Omni and tore up his knee, putting him out for the remainder of the year. Cleveland beat the Hawks that night to move to 9-7, than lost eighteen of the next twenty and spent the remainder of the year out of the playoff picture. Expected to win fifty games prior to the 1990-91 season, the Cavaliers needed an 8-2 close-out run just to avoid losing fifty.

Two seasons earlier, Cavs fans thought that in Price and Ron Harper, they had the guard tandem of the ‘90s. Now, with Harper in Los Angeles, and Price sidelined, they watched the likes of Steve Kerr and Darnell Valentine log major minutes in the Cleveland backcourt. Meanwhile, the newly arrived Danny Ferry, Harper’s trade counterpart, proved to be a slow, un-athletic, 6’10” jump shooter that got less respect from the officials than any player in NBA history, and tied up more salary cap room than most of them.

The following season basically the same team, with a healthy Mark Price, went 57-25 and reached the Eastern Conference Finals. LeBron James isn’t the only player in Cavaliers history whose presence single-handedly made the difference between Cleveland being one of the NBA’s best teams, and one of its worst.

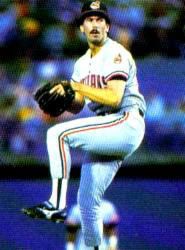

Indians: 57-105, 7th AL East

Story- my older brother and Cleveland Sports mentor went to 21 Tribe games during the 1991 season, which was a personal record for him. The bulk of his attendance came in August and September, when it had long become apparent that the club was transcendently bad. He rarely referred to the Indians as “the Indians”, or “the Tribe”, or any of the preferred nomenclature. They were “the awful team”. He’d get his keys, put on his Indians Starter jacket and fitted cap, and say, “I’m going up to see the awful team, wanna come?”

Sometimes I would (we would arrive in the second inning, park on Lakeside for free, and get the twelve-dollar box seats at the gate). When I didn’t, he’d tell me I wasn’t a real fan. As the losses mounted, my brother’s interest in the team crossed over into a zeal that was almost religious. It was by design that he set his personal record in 1991. He considered that season the crucible. It was the ultimate test for an Indians fan.

Because 1991 was as bad as it could possibly get.

By the standards of those old Indians teams, the ‘91 season didn’t start out too terribly. On June 5, John McNamara’s Tribe was 21-28 and only six games out in the American League East. They proceeded to go 6-30 over the next month-and-a-half. Included in this tortuous stretch were two five-game losing streaks, a six-game losing streak, and a seven-game losing streak. The Tribe scored two runs or fewer in 21 of those 36 games and was shut out seven times, including three games in a row in mid-June. In early July, with the club at 25-52, manager Johnny Mac was fired, probably to his relief. Mike Hargrove took over and did marginally better, going 32-53. When it was over, Cleveland’s 57-105 record was the worst in major league baseball by a full eight games. The ’91 Tribe also set a new franchise record for losses in a season- a record that hopefully will never be broken.

This was the year the Indians moved the fences back at Municipal Stadium and re-tailored the offense around Alex Cole. What they really did was re-tailor the offense around sucking. Cole, who’d become a sensation the previous year by stealing 40 bases in 63 games (including a club-record five in one game), did hit .295, and did steal 27 bases. He was also caught 17 times, played a brain-dead center field, got picked off at a Herb Washington rate ,and hit zero home runs in 387 at-bats. Sandy Alomar, the AL Rookie of the Year in 1990, was limited by injuries to 184 at-bats and hit a stellar .217. (He started in the All-Star Game anyway.) The Tribe hit an anemic 79 home runs as a team, a league low that went with their AL-worst run total like rat-gnawed chocolate and rancid peanut butter.

Well over a third of those home runs- 28- came off the bat of Albert Belle, who also drove in a team-high 95. The newly-renamed Albert still had Joey’s temper though, and Belle’s 1991 season is best-remembered for being the year he implanted a baseball in the chest of a heckling fan. He was briefly sent down to the minors during the team’s early-summer free-fall for failing to run out a double-play ball. Fans wondered if the prodigiously talented Belle could ever get his raging fury under control, and old hands nervously compared him to Tony Horton, another gifted Indian who couldn’t get out of the way of his own demons.

While a young star exploded, an old one imploded. Doug Jones, who had averaged 37 saves the previous three seasons, tipped off his curveball in 1991 and had his mustache repeatedly blown flat against his face in the wake vortexes of shots hammered off of opposing bats. Jones ended the year with a 5.54 ERA and seven saves, and was so bad in the closer’s role that late in the season the Tribe experimented with him as a starter.

Jones, Greg Swindell, Tom Candiotti, Jerry Browne, and Brook Jacoby- the closest thing to stalwarts the old Indians had- left the club during or after the 1991 season (Jacoby, dealt to the A’s in late 1991, would return in ‘92 to play one more season in Cleveland, and Candiotti and Jones each briefly came back years later). In their places came youth, and unlike many previous Tribe youth movements, this one had the proper ingredients. Sandy Alomar was the 1990 AL Rookie of the Year and was 25. The 25-year old Belle was already one of the best young sluggers in baseball. 24-year old Charles Nagy pitched his first full season and did credibly, going 10-15 with a 4.13 ERA. 22-year old Carlos Baerga hit eleven home runs and knocked in 69. Twenty-year old Jim Thome saw his first major-league action. And in the 1991 amateur draft, the Indians used their first-round pick on an eighteen-year old New York City prodigy named Manny Ramirez. Soon the trickle of talent became a floodtide. Just three years removed from 1991’s season from hell, the Indians, playing in a beautiful new ballpark, would be the most dynamic young team in the game.

Starting with the goofy idea to move the fences back, 1991 seems almost like as much a caricature of the bad old days of Indians baseball as Chief Wahoo is of a real native. It was a 162-game summing up of the plagues, problems, and misfortunes- injuries, strategic ineptitude, terrible attendance, revolving managers, and plain old bad baseball- that beset the Tribe franchise for nearly four decades. It was one last, grand bloodletting before the revival.

Silver Linings of ‘91

- Bernie Kosar set an NFL record by throwing 308 consecutive passes without an interception (a streak he had started the previous season). Even after he’d lost his mojo on the field, the old Boardman Spartan could still throw a football through a tire better than Montana, Young, Moon, Elway, or anyone else.

- On May 4 in a 20-6 rout of the Athletics, the Tribe’s Chris James went 4-for-5 with two home runs and a club-record nine RBIs. Other than this one afternoon, James’s 1991 season, like his club’s, was a disaster; the new dimensions at the Stadium gave him warning track power only, and in 221 home at-bats, Craig’s brother went gonzo but once.

- On December 30, LeBron James turned seven. The next night, the year ended. That’s about it.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

HoodooMan (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:32 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)