General

General  General Archive

General Archive  The 20 Biggest Cleveland Sports Stories That Would Have Broken the Internet - Part 1

The 20 Biggest Cleveland Sports Stories That Would Have Broken the Internet - Part 1

A few weeks ago, while at the Indians game with some of our fellow writers at The Cleveland Fan, there was a point in the game where we looked around and seemingly everyone in our group was busy looking down and tapping away on some kind of device.

A few weeks ago, while at the Indians game with some of our fellow writers at The Cleveland Fan, there was a point in the game where we looked around and seemingly everyone in our group was busy looking down and tapping away on some kind of device.

Being the only person in the group without a smart phone made us realize how much technology and social media has changed the way we watch and interact during sports events. We can be at home on the couch, at the stadium or the arena, and still interact with a community of Indians, Browns and Cavs fans across the country and around the world through Twitter, Facebook and e-mail. (And that doesn’t even take into account the numerous high-quality fans sites devoted to Cleveland sports).

That got us thinking about some of the biggest Cleveland sports moments in our lifetime in the pre-blog and social media era, which we are defining as anything before 2004. Because while Syknet may have become self-aware in 1999, sports blogs didn’t become prevalent in town until 2004, the same year Facebook was created, and Twitter did not launch until 2006.

So we came up with the 20 biggest sports stories that would have made the Internet blow up in Cleveland had these various social media platforms existed at the time. We’re starting today with Part One, highlighting No. 20 to No. 16.

20. Joe Carter traded to San Diego

Before the ’89 season, Carter turned down a five-year, $9.6 million contract offer from the Indians (how financial times have changed) and team officials were convinced Carter would not resign with the Tribe and decided to move the biggest star on the team (some things haven’t changed).

“We wanted to keep Carter, but when he turned down the $9 million his agent told us that he just did not want to stay with the team,” Hank Peters, general manager at the time, said in Terry Pluto’s 1994 book The Curse of Rocky Colavito. “Rather than lose him to free agency at the end of the 1990 season, we set out to make the best deal we could for him.”

Once the Tribe decided to trade Carter they had plenty of interested teams. According to a Los Angeles Times article on Dec. 5, 1989, the Angels offered outfielder Devon White and second baseman Johnny Ray, the Royals offered Danny Tartabull and reliever Jose DeJesus, the Cardinals were willing to part with outfielders Willie McGee and Vince Coleman, and Toronto offered second baseman Manny Lee, outfielders Junior Felix and reliever Duane Ward.

The Indians eventually traded Carter to San Diego for Carlos Baerga, Sandy Alomar Jr. and Chris James. In six-and-a-half seasons with the Indians Baerga hit .300 and averaged 16 home runs and 86 RBI a season, with a four-year stretch (1992 to 1995) where he batted .300 or better. In 11 years, Alomar hit .277, was named Rookie of the Year in 1990 and was a six-time All Star. The pair were part of a powerhouse team that made the World Series in 1995 and Alomar hit one of the biggest home runs in team history when he took New York’s Mariano Rivera deep in the 1997 playoffs.

Clearly the Indians succeeded in their plan to take the best deal available.

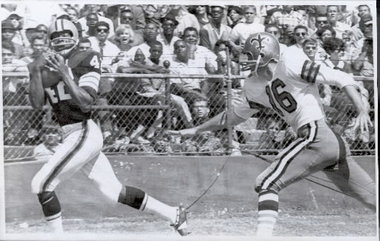

19. Paul Warfield traded to Miami

Heading into the 1970 season, the Cleveland Browns needed a quarterback. (Where have we heard that one before?) Bill Nelsen was nearing the end of his career and the team – dominant during the 1950s and 1960s – needed someone who could keep the team in playoff contention for the next decade. They decided that man was Mike Phipps.

Heading into the 1970 season, the Cleveland Browns needed a quarterback. (Where have we heard that one before?) Bill Nelsen was nearing the end of his career and the team – dominant during the 1950s and 1960s – needed someone who could keep the team in playoff contention for the next decade. They decided that man was Mike Phipps.

The Miami Dolphins held the No. 3 pick in the 1970 NFL Draft but already had a quarterback in Bob Griese – who ironically had preceded Phipps at Purdue. So the Browns sent Warfield, who had been with the team since 1964, was a three-time Pro Bowl selection who had averaged 20.5 yards per reception and almost nine touchdowns a year, to Miami for the right to draft Phipps.

“I know the Browns didn’t want to trade me,” Warfield said in Terry Pluto’s 1997 book, When all the World was Browns Town. “But they felt they had to get a young quarterback because of Bill Nelsen’s knees. The Dolphins knew the Browns were in love with Mike Phipps and they said they’d draft Phipps and then demand even more than me in a trade later, so the Browns gave me.”

Warfield went on to play in three Super Bowls (winning two) with the Dolphins, making the Pro Bowl each of his five years in Miami, before closing out his Hall of Fame career with a two-season cameo back in Orange and Brown (1976 and 1977).

To make matter worse, with Warfield in Miami the Browns found themselves in need of a wide receiver. So they traded defensive lineman Jim Kanicki, running back Ron Johnson and linebacker Wayne Meylan to the New York Giants for receiver Homer Jones, who lasted one year with the Browns, catching 10 passes for 141 yards.

As for Phipps .. well ... he wasn’t the answer at quarterback. In seven years with the Browns, he made 52 starts, throwing 40 touchdown passes against 81 interceptions. He did lead the Browns to the playoffs in 1972 with a 10-4 record, but the team quickly went downhill after that, finishing 7-5-2 in 1973, 4-10 in 1974 and 3-11 in 1975. Phipps gave way to Brian Sipe in 1976 and was traded to Chicago before the following season.

Phipps played what was perhaps his best game on Nov. 23, 1975, against Cincinnati, one of the 50 greatest games in team history according to Jonathan Knight’s 2008 book Classic Browns. Phipps threw for 298 yards and two touchdowns to rally the Browns to 23 consecutive points in a 35-23 win.

The victory broke a nine-game losing streak (at the time the longest in franchise history) and for one day Phipps made fans forget about the lopsided trade.

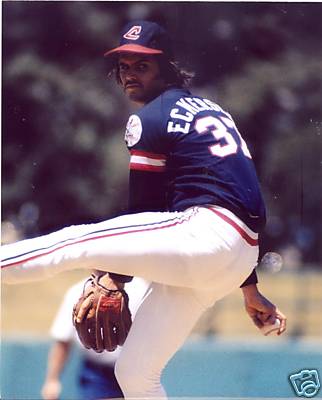

18. Indians trade Dennis Eckersley

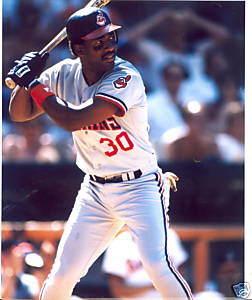

In 1972, the Cleveland Indians had the kind of draft that can transform a team, selecting Rick Manning in the first round and Dennis Eckerlsey in the third. They were part of a talented group of youngsters that included Duane Kuiper, Jim Kern and Buddy Bell that were going to wake the sleeping giant and return the Indians to the top of the American League East standings.

In 1972, the Cleveland Indians had the kind of draft that can transform a team, selecting Rick Manning in the first round and Dennis Eckerlsey in the third. They were part of a talented group of youngsters that included Duane Kuiper, Jim Kern and Buddy Bell that were going to wake the sleeping giant and return the Indians to the top of the American League East standings.

Starting that summer, when Manning and Eckersley roomed together at Class A Reno, the duo were inseparable.

Eckersley made it to the majors first, in 1975, and in his first major league start on May 28 he threw a shutout against Oakland. He didn’t allow an earned run in his first 28.2 innings of work on the major league level.

By June of that year, Manning, Kuiper and Kern joined the Indians roster, along with Eckersley and Bell, and helped the Tribe to a final record of 79-80, the most wins for the team since 1968.

By 1977, Manning and Eckersely were in full swing. Manning followed his rookie season, where he hit .285, by batting .292 and earning a Gold Glove as a center fielder in 1976. Eckersley had matured into a talented starting pitcher, throwing a no hitter against California that was part of a streak that saw him throw 22.1 consecutive hitless innings.

Things started to fall apart on June 4 of that year, when Manning injured his back on a headfirst slide into second base. Manning was in a brace for six weeks and was out of the lineup until September. During that time he stayed at Eckersley’s house and drew close to Eckersley’s then-wife, Denise.

“I clearly remember that we knew what was going on between Rick and Eckersley’s wife,” former general manager Gabe Paul said in The Curse of Rocky Colavito. “We had to trade someone before the whole thing blew up in our faces. Manning had the bad back and his trade value was down. Besides, I really though he’d be one of the great stars. Boston wanted Eckersley badly, so we made the deal. It turned out that Eckersley became the star. He always was a great performer and he never let his troubles affect his pitching.”

On March 30, 1978, the Indians made the decision to trade Eckersley to the Red Sox for Rick Wise, Mike Paxton, Bo Diaz and Ted Cox. Eckersley went on to win 129 more games after he left Cleveland and saved 390 as he revolutionized the closer’s role during a Hall of Fame career (this seems to be a theme). From 1988 to 1992 he averaged 47 saves a year for Oakland and won the Cy Young and MVP awards in 1992, when he saved 51 games.

“What I found out is that times heals a lot of things,” Eckersley said in The Curse of Rocky Colavito. “It has been a long time since I first came to the big leagues with the Indians.”

As for the players the Indians got in return, Wise went 24-29 in two seasons in Cleveland before leaving as a free agent to San Diego. Paxton went 12-11 for the Tribe, hurt his arm and was out of baseball by the age of 25. Diaz eventually became an All-Star after the Indians traded him to Philadelphia for Larry Sorenson. Cox was eventually trade by the Indians and only played in 272 major league games, hitting .245 with 10 career home runs.

Quite a haul by the Tribe’s front office.

Manning ended up having a decent 13-year career with the Indians and Milwaukee, but was never the same offensive player after his back injury. In nine seasons with the Tribe he was a .263 hitter and only batted above .270 twice in a season after his injury. He retired in 1987 and was hired in 1989 as one of the Indians TV broadcasters, a job he still holds today as one of the more under-rated announcers in baseball.

“The thing with Eck and Denise might have hurt my image, but people don’t know the whole story,” Manning said in The Curse of Rocky Colavito. “I know the truth and what people think doesn’t bother me at all. I know what happened. That’s life. You can’t change history.”

17. Len Barker’s perfect game

It was a typical early season game for the Indians on May 15, 1981. Cold and wet, with only 7,290 fans in the seats at Municipal Stadium as the Tribe took on Toronto. The game was televised, though, something that didn’t always happen in those days.

It was a typical early season game for the Indians on May 15, 1981. Cold and wet, with only 7,290 fans in the seats at Municipal Stadium as the Tribe took on Toronto. The game was televised, though, something that didn’t always happen in those days.

Len Barker was coming off a season where he won 19 games and led the American League in strikeouts with 187. He was talented but often had trouble harnessing that talent.

“Lenny went into that night as a guy who was known as a great seven-inning pitcher,” broadcaster Nev Chandler said in The Curse of Rocky Colavito. “Then he’d get tired and they’d have to get him out of there. Herb (Score) and I had talked about Lenny throwing a no-hitter one day. It was not uncommon for him to go into the firth or sixth inning without allowing a hit, but then something would always happen to him.”

Barker used a sharp curveball that night against the Blue Jays, throwing it 70 percent of the time. He stuck out 11 of the last 17 batters of the game and the game ended on a fly out to none other than center fielder Rick Manning.

“That was one of the most unreal days of my life,” Barker said in The Curse of Rocky Colavito. “I knew that I had good stuff, maybe even awesome stuff, when I began the game. But as the game went on, I had total command. I could throw anything, anywhere I wanted.”

Barker’s perfect game was the 10th in Major League Baseball history and the second in the Tribe’s history, along with Addie Joss’ perfect game on Oct. 2, 1908 vs. the White Sox. In addition, it was the third no-hitter (and currently the last one in franchise history) that a Tribe pitcher had thrown in just a seven-year period – all at home. Prior to Barker, Dick Bosman threw a no-hitter against Oakland on July 19, 1974, and Dennis Eckersley no-hit the Angels on May 30, 1977.

So while the Indians did not give fans much to cheer about during the 1970s, on occasion they did give fans a special night at the ballpark.

16. Albert Belle corks his bat

The Cleveland Indians and Chicago White Sox were locked in a pennant race when the Tribe traveled to Comiskey Park for a series in mid-July of 1994.

The Cleveland Indians and Chicago White Sox were locked in a pennant race when the Tribe traveled to Comiskey Park for a series in mid-July of 1994.

Tribe slugger Albert Belle was in the midst of a year that would see him bat .357 with 36 home runs and 101 RBI in a strike-shortened season.

In the first inning of the Friday night game of the series, White Sox manager Gene Lamont asked umpires to confiscate Belle’s bat because the White Sox suspected it was filled with cork. The umpires impounded the bat with plans to ship it to the league office in New York City for x-rays.

During the game, someone from the Indians crawled 30 feet through the ceiling to an escape hatch in the umpires’ dressing room, dropped down through an escape hatch and replaced Belle’s bat with one of teammate’s Paul Sorrento’s bats.

Vince Fresso, who took care of the umpires’ room, discovered the theft in about the sixth inning when he noticed clumps of ceiling insulation on the floor, according to a story in The Chicago Tribune. Ceiling tiles in two locations were askew and the metal support strips twisted out of shape.

Major League Baseball began an investigation, going so far as to bring in a former FBI agent to help find out what happened. It wasn’t that hard to figure out something was wrong as, according to umpire Dave Phillips, the bat he took from Belle was a “shiny new bat” while the replacement was “extremely dirty and sticky with pine tar in several places. It looked like it had been used for a long time.”

A day later, the correct bat was found and given to Tribe manager Mike Hargrove, who turned it over to league officials. Belle received a 10-game suspension that was reduced to seven games on appeal.

It wasn’t until 1999 that the player who stole the bat was identified as reliever Jason Grimsley.

“That was one of the biggest adrenaline rushes I’ve ever experienced,” Grimsley told The New York Times in admitting his role. “My heart was going 1,000 miles a second. I just rolled the dice, a crapshoot.”

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

HoodooMan (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:36 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)