General

General  General Archive

General Archive  Cleveland Sports Vault: 1977-1980. Ted Stepien, Mike Zarefoss and Cleveland Softball

Cleveland Sports Vault: 1977-1980. Ted Stepien, Mike Zarefoss and Cleveland Softball

Men’s amateur slow-pitch softball exploded in the 1970s. On any day of the week, teams could be found slugging it out on baseball fields all over the country.

Men’s amateur slow-pitch softball exploded in the 1970s. On any day of the week, teams could be found slugging it out on baseball fields all over the country.

Softball had been played in northeast Ohio for fifty years, and was part of the evolution of baseball in Cleveland. Part of its popularity was that like hardball, it could be played at a highly skilled level. Or, it could be played at a more relaxed pace.

Throughout the middle part of the century, Cleveland’s sandlots had been an important breeding ground of major league ballplayers. Teams represented factories, unions and various businesses.

By the ‘70s, those sandlot fields had now become meccas for softball. Businesses and local taverns sponsored teams, both within the city limits and throughout the suburbs.

One such sandlot was Morgana Park, near the zoo. Nestled into the corner of 65th and Broadway, that park was renowned for its rich history, and for the elevated public stage it had become. The field featured almost no foul territory, and vocal fans were right on top of the players. The distance to the outfield fence was short to left and right fields, and deep to center. The PD Major League played there, with such notable teams as Sheffield Bronze, Pyramid Café, and Non-Ferrous. The Plain Dealer ran articles and the box scores of the games.

renowned for its rich history, and for the elevated public stage it had become. The field featured almost no foul territory, and vocal fans were right on top of the players. The distance to the outfield fence was short to left and right fields, and deep to center. The PD Major League played there, with such notable teams as Sheffield Bronze, Pyramid Café, and Non-Ferrous. The Plain Dealer ran articles and the box scores of the games.

I remember a tournament our dad’s team played there. He was the long-time pitcher of his team, and every single teammate had a nickname. It was stitched into the jersey each of them wore, in cursive. The jerseys were a shiny, dark yellow, with curved red and white stripes on the side and around the neck, bordered in black. Just under the chest, to the side, was a large round patch: “Shippe’s Auto Body” (it’s still in business). That tournament at Morgana was maybe Shippe’s’ best run of softball ever. With each win, they got more serious- in a focused, confident way. My brother and I had the best vantage point of anyone- we were batboys.

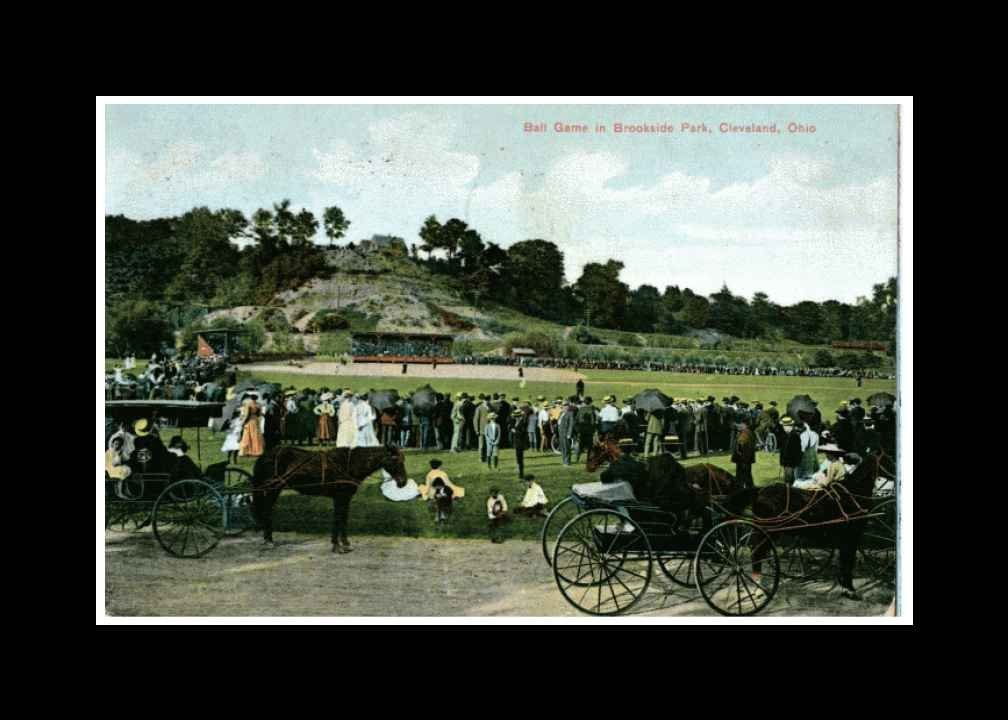

Dad played in two leagues; one held its games at Mentor High School and the other was on Sundays at Brookside Park in Cleveland (in the Metroparks next to  I-71). Brookside has its own fascinating history. It is featured in this video, although it appears the baseball field orientation has changed over time. One hundred years ago, before the trees of today graced the hills, the recessed area was a popular venue for factory baseball teams. Cleveland squads faced visiting teams from various towns, occasionally in front of over 100,000 spectators (that is not a typo).

I-71). Brookside has its own fascinating history. It is featured in this video, although it appears the baseball field orientation has changed over time. One hundred years ago, before the trees of today graced the hills, the recessed area was a popular venue for factory baseball teams. Cleveland squads faced visiting teams from various towns, occasionally in front of over 100,000 spectators (that is not a typo).

When we watched Dad’s softball games at Brookside in the ‘70s, a recurring treat was the activity on the steep hill (cliff) that could be seen beyond center field. (I think that is the cliff shown in the postcard.) Every so often, mini bike riders tried to scale the incline. They’d work up a head of steam as they approached the cliff, the noise attracting the attention of onlookers. The bikes always made it at least halfway up. Keeping their momentum and reaching the top edge and driving away and out of sight happened perhaps three out of four times. When they didn’t make it, they became, well, stuck on the side of a cliff, in plain view of a crowd of observers. That was when it got interesting. How would they get back down, and would they take a tumble? Would the bike? See bottom of article for another great photo of Brookside Park from the early 1900s.

***

A wealthy advertising executive named Ted Stepien would purchase enough shares of the Cleveland Cavaliers pro basketball franchise to become controlling owner in 1980. He would buy them from Joe Zingale, whom had bought out Nick Mileti the year before. Zingale, a radio executive, had previously been a minority owner. He had had ownership in various other interests as well, such as Cleveland’s 1970s pro tennis team.

History has not looked kindly on Ted Stepien. He replaced Cavalier coach Stan Albeck with Bill Musselman of the University of Minnesota. (He was the coach of the Gopher team that physically attacked Luck Witte and the Ohio State Buckeyes on the court a few years earlier.) Musselman favored a methodical style of play, so the Cavs’ roster required an overhaul. The problem was, Stepien was clueless as how to assess the talent of players they looked to bring aboard. For example, he dealt Foots Walker and Campy Russell in ill-conceived trades- but the trades he is most noted for involved the wanton discarding of first round draft picks. He traded so many first round picks that the NBA commissioner declared a moratorium on deals involving Stepien. A permanent league rule  was instituted that prohibits teams from trading successive first round draft picks-this is commonly known as the Stepien Rule.

was instituted that prohibits teams from trading successive first round draft picks-this is commonly known as the Stepien Rule.

Do you know the man to the left? He is from North Royalton. His name is Paul Porter, and he is the Orlando Magic PA announcer. He once was the PA announcer for the Cavaliers, and became their radio voice in 1981 when Ted Stepien fired Joe Tait. Now, I am sure Paul Porter can boast of several socially redeeming qualities. But yeah, Ted Stepien once fired the institution for whom a microphone banner now hangs in the rafters at Quicken Loans Arena.

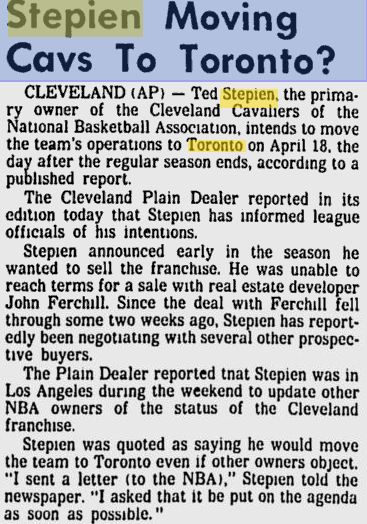

Ted Stepien had plans to hold “home” games in various cities not named Cleveland. He was constantly harangued by another Cleveland institution at the time, sports talk show host Pete Franklin. Franklin called out Stepien on the incompetence of the moves he made with the Cavaliers. He accused Stepien of wanting to move the Cavs to Toronto, and calling them the Toronto Towers. It turned out that Stepien did tell supporters in Toronto that he intended to do just that. (In my opinion, Clevelanders need to remember the truth about Art Modell’s lies about having no choice but to move the Browns. If we don’t, nobody will. In the same vein, I

Stepien was friends with the coach of Lakeland Community College, Don Delaney. By all accounts, Delaney was a nice guy, but for some reason Ted Stepien considered him to be qualified for the general manager position for the Cleveland Cavaliers. When Bill Musselman was fired at the end of his one miserable  season, Stepien installed Delaney as coach. Stepien’s gutting of the roster, combined with his stated intention to have a strong representation of whites on the team (since having too many blacks would not be a smart move in a predominately white demographic market) spelled disaster for the franchise.

season, Stepien installed Delaney as coach. Stepien’s gutting of the roster, combined with his stated intention to have a strong representation of whites on the team (since having too many blacks would not be a smart move in a predominately white demographic market) spelled disaster for the franchise.

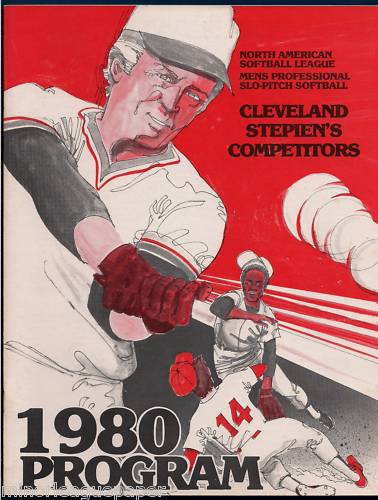

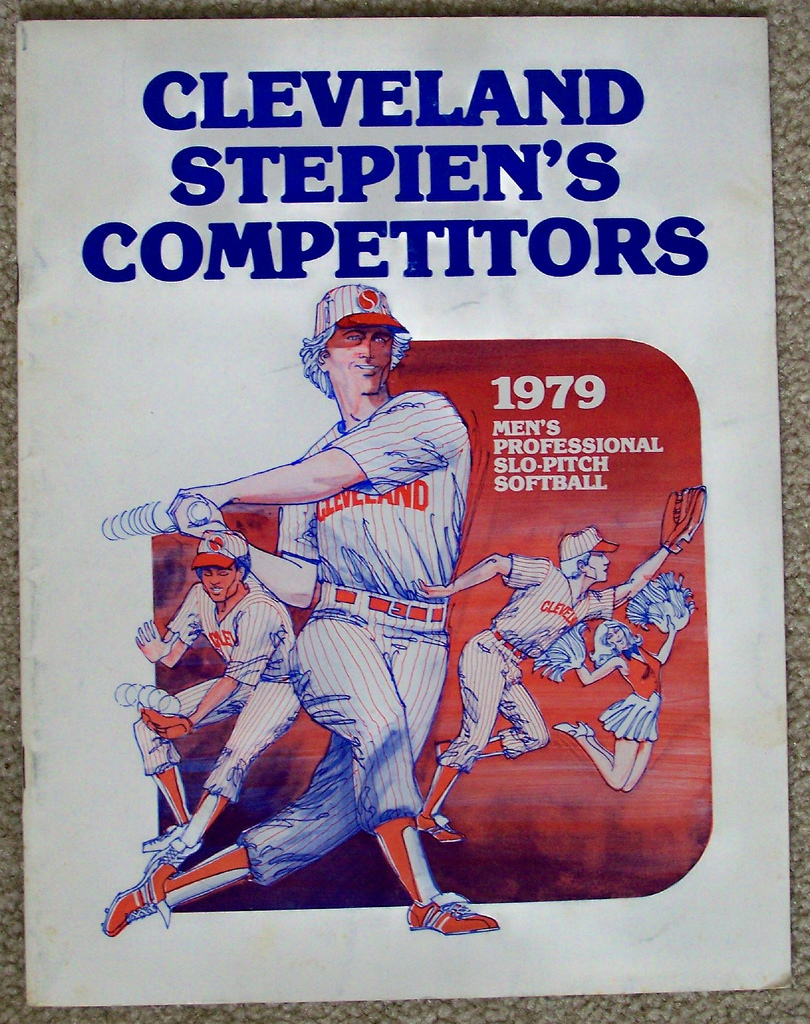

Ted Stepien observed the popularity of softball in the late 1970s, when the high-profile figures in the game were all home run hitters. It had become a game of power. Stepien owned a facility known as “Softball World” near Cleveland’s Ford and Chevrolet factories. He saw the draw of that venue, and desired to make a go of a professional league. He took over a team known as the Cleveland Jaybirds, and changed the name to the Cleveland Stepien Competitors. The status and size of the league was somewhat fluid, but at one point he apparently owned eight of the ten teams in the league. He signed ex-Yankee and Cub Joe Pepitone to lead the Chicago team.

The league rules included:

Nine inning games.

Three balls for a walk; two strikes for a strikeout.

A foul ball after a strike was an out.

Stealing was permitted after a pitched ball crossed the plate.

Bases were 70 feet apart.

They basically promoted pro softball in much the same way minor league baseball promotes itself today- with a family atmosphere, and cheaper prices for tickets, food and parking. Teams commonly played doubleheaders, and tickets typically cost $2 for adults and $1 for children.

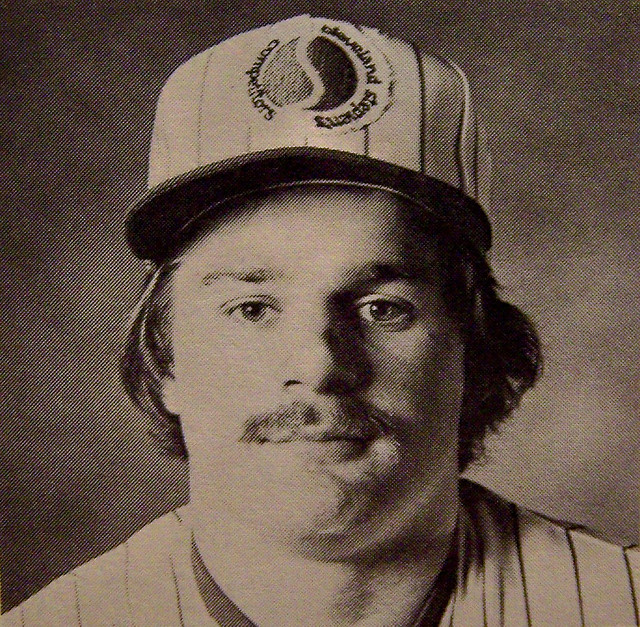

Stepien recalled the story of the time Cleveland Indians rookie third baseman Ken Keltner threw baseballs off the top of the Terminal Tower in downtown  Cleveland, to the three catchers on the Indians roster who were waiting down on Public Square. It was a pro-Cleveland publicity stunt, and eventually, a couple balls were caught. In 1980, Stepien had the bright idea of throwing softballs off the Tower, to players on his Competitors softball team. After several misfires, Competitors player Mike Zarefoss (right) ran toward the crowd and caught one.

Cleveland, to the three catchers on the Indians roster who were waiting down on Public Square. It was a pro-Cleveland publicity stunt, and eventually, a couple balls were caught. In 1980, Stepien had the bright idea of throwing softballs off the Tower, to players on his Competitors softball team. After several misfires, Competitors player Mike Zarefoss (right) ran toward the crowd and caught one.

It’s a miracle someone didn’t get killed. First, the Indians in the ‘30s wore steel helmets. No such protective gear was worn by the Competitors. But most disconcerting: the onlookers in 1980 were unwittingly in the line of fire. One was grazed by a softball, and a woman suffered a broken wrist when she was struck. One ball crashed through a car windshield. The problem was that there was no telling where the balls, traveling at 144mph, were going to end up. Speaking to Channel 5 News outside his Competitors Club restaurant, Stepien assumed no blame for putting the public in danger. (And come on- those people did not need to be so clueless as to put their kids in harm’s way. On the other hand, this was the generation that allowed their children to ride their bicycles in thick white clouds of DDT. The fog trailed the trucks the suburban authorities sent around neighborhoods in the summer, to kill mosquitos.) Stepien answered some pointed questions from Channel 5, before sneaking in a plug at the end of the piece for Cavalier ticket sales.

The Cleveland Competitors’ league lasted through the 1980 season, after undergoing some turbulent reorganization as it tried to stay afloat financially. They tried to partner with the fledgling cable television industry. It actually seems they were trying to do some things right, before folding.

Ted Stepien was a lot of things, and referred to by many names, by many people. Would-be softball visionary may not rank very high on the list, but it fits.

Thank you for reading. Here is another photo of Brookside Park.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

mattvan1 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:19 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)