General

General  General Archive

General Archive  Cleveland Sports Photo Journal: League Park

Cleveland Sports Photo Journal: League Park

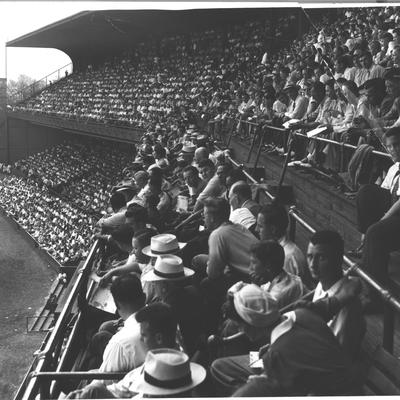

Baseball in the United States was a powder keg that was about to detonate. One ignition source was the post-World War II return of hundreds of thousands of military and support personnel. Another was the postwar economy. The war had delivered the country from Great Depression to an historic boom. Baseball exploded, surpassing boxing as the top American sport.

Baseball in the United States was a powder keg that was about to detonate. One ignition source was the post-World War II return of hundreds of thousands of military and support personnel. Another was the postwar economy. The war had delivered the country from Great Depression to an historic boom. Baseball exploded, surpassing boxing as the top American sport.

At this very time, Cleveland’s League Park was fading into the past. Its increased capacity had peaked at under 23,000, which was increasingly insufficient for the nation's "Sixth City". It was also showing the wear of its half century of use. And, perhaps most urgently at the time, it was completely landlocked.

Of course, during the useful life of the ballpark, its location was useful. Strategic, even. Dating back to the 1890s, two electric streetcars served Hough and Euclid avenues. Patrons of League Park thus had easy access to the games.

But the Henry Fords of the world were fueling consumers' desire to purchase automobiles, and there was no room for parking. The owners of the adjacent properties were unwilling to sell. (Photo at right is of along Lexington Avenue, and the tall, lighter colored structure is the right field boundary of the ball park. On another scale, Municipal Stadium's "Gate D" area.)

of along Lexington Avenue, and the tall, lighter colored structure is the right field boundary of the ball park. On another scale, Municipal Stadium's "Gate D" area.)

So right at about the time the nation's journalists began to train a magnifying glass on baseball, League Park was becoming a memory. But if we search diligently, we can knit together a multi-dimensional impression of the venue.

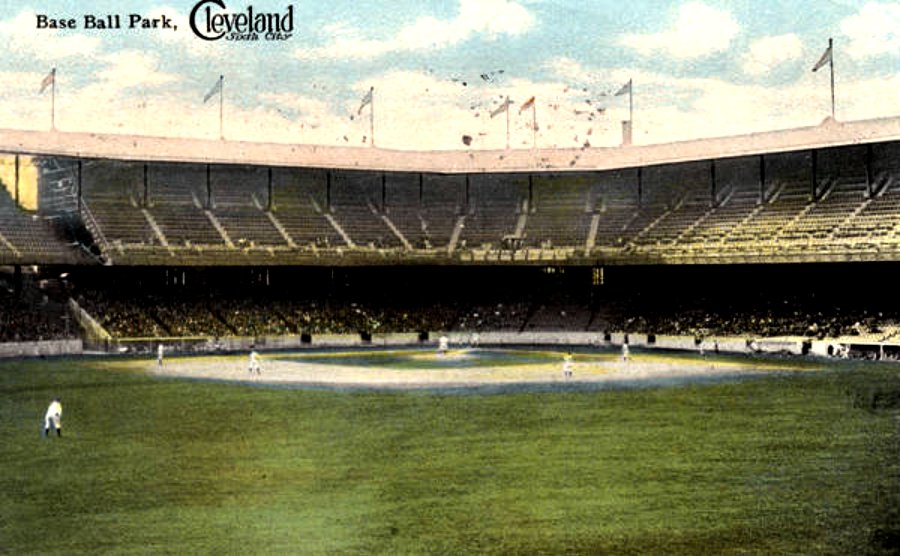

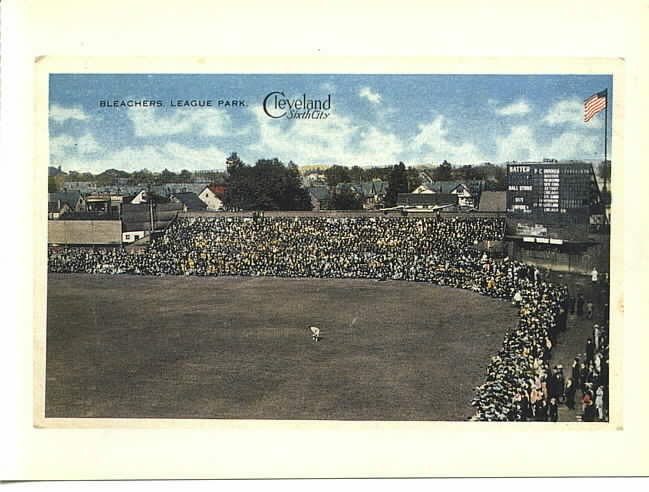

In the parlance of Tribe announcer Tom Hamilton, the structure itself (by 1910; it had undergone renovations) was mostly a two-deck affair, with a roof. Hugging the left field corner was a section of bleachers. Centerfield tapered to a point, 420 feet from home plate, where the large scoreboard stood. Right field was close - 290 feet down the line. It hugged Lexington Avenue, which bordered the property on its south side. However, the five-foot wall was augmented with a fence that stood 60 feet high (compare that to the 37 ft high Green Monster at Fenway Park in Boston). The photo of the boys peeking in at a game at the top of this piece was taken from Lexington Avenue, behind right field. Entertainer Bob Hope, who grew up a few blocks away, used to talk about how he and his friends would peek through these holes and catch Indians games. Hope's favorite player was center fielder- and player-manager - Tris Speaker. The "Grey Eagle", along with Detroit Tiger Ty Cobb, had been perhaps the biggest non-pitcher stars in baseball, in the years just prior to Babe Ruth's debut in 1914.

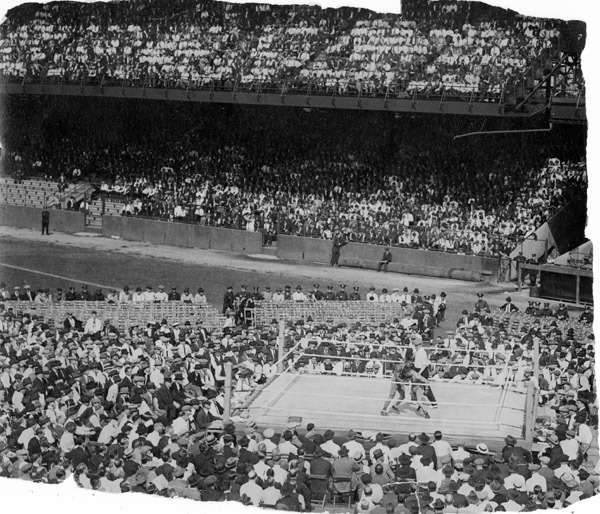

While League Park was the home of Cleveland's big league ball clubs (the Spiders, the Blues, the Bronchos, the Naps, and then the Indians as of 1915), the venue was also the home of various other tenants. Here is a photo of a boxing match held at the ball park.

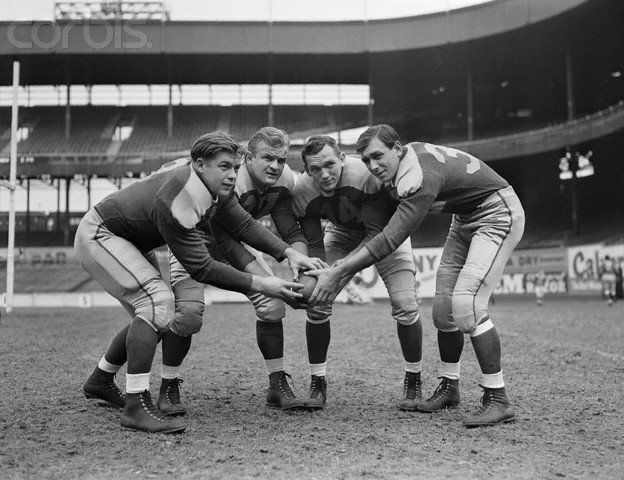

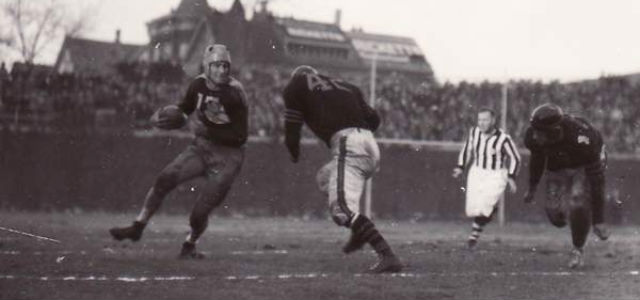

Sometimes overlooked in Cleveland sports history are the Cleveland Rams. They played NFL games at League Park. (They also played for a time at Shaw high school- remember, football had not yet become nearly as popular as it would later be.) Below left is the starting backfield of Corby Davis, Rudolph Mucha, Johnny Drake, and Parker Hall. Below right features your Cleveland Rams getting a pass rush on a Green Bay Packer quarterback.

UCLA quarterback Bob Waterfield would be drafted by the Rams in 1945. The future Hall of Famer had a great rookie season, becoming a local favorite in Cleveland. He was the league's Most Valuable Player, and unanimous All-NFL. He led Cleveland to an NFL championship, hitting on 37 of his 44 passes in the title game. The Rams beat the Washington Redskins,15-14, on a minus eight degree day (the championship game was actually played at Municipal Stadium). A great read is this piece on Waterfield, by Andrew Clayman. It is a two-parter, and Part Two is linked here.

The Cleveland Rams (named after those fine men of Fordham University, by the Cleveland team's founder) were moved to Los Angeles in 1946. Serious competition was moving into town, in the form of Mickey McBride's new All American Football Conference football team. For his team, as yet unnamed, McBride had been determined to make

Rams owner (and future Hall of Famer himself) Dan Reeves that Reeves bailed, moving to Los Angeles. McBride also had secured a long-term lease with the(much) larger Municipal Stadium, which factored into Reeves' decision.

Rams owner (and future Hall of Famer himself) Dan Reeves that Reeves bailed, moving to Los Angeles. McBride also had secured a long-term lease with the(much) larger Municipal Stadium, which factored into Reeves' decision.

The Cleveland Bulldogs of the NFL had also called League Park its home, and they won a title in 1924.

The Western Reserve Red Cats played home games there, as well.

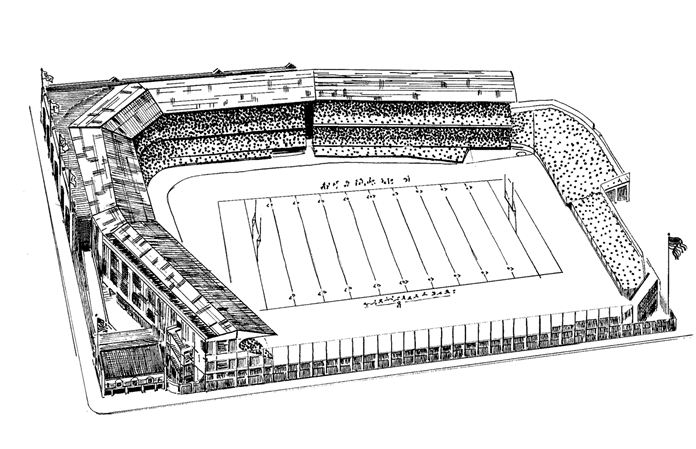

League Park served as the training facility for the Cleveland Browns for the first several years of their existence. The sketch provided here is intended to give an idea of the layout of the gridiron.

Of course, big league baseball was the primary tenant of League Park. I say tenant, though that is a misnomer: in its era, big league owners also owned the home ball park of the team. Cleveland's Municipal Stadium was the first to be publicly-funded. In fact, after hosting a heavyweight title bout featuring Max Schmeling of Germany, the Stadium was without a tenant of its own for about a year. The owner and the city haggled for a while before agreeing to terms.

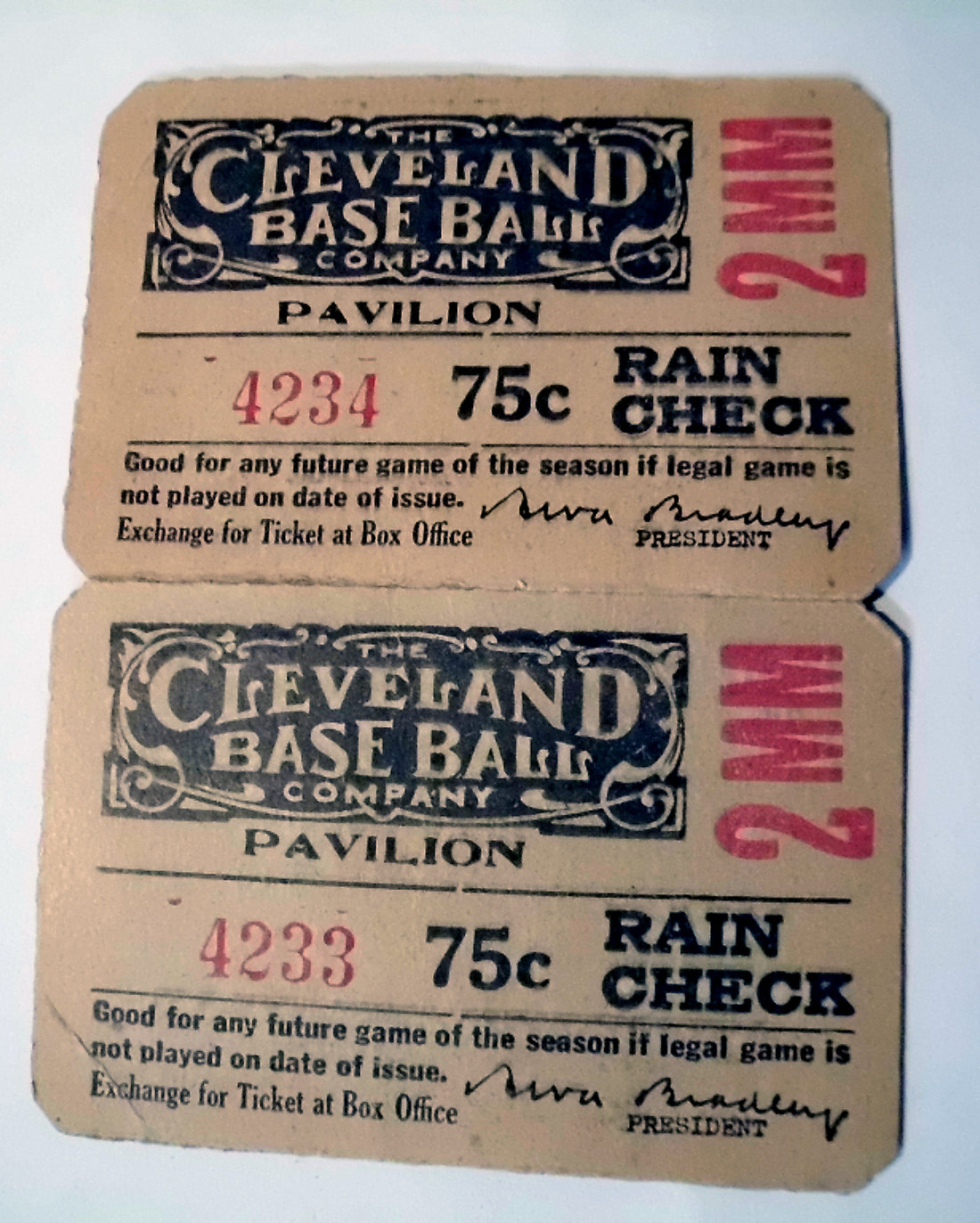

Perhaps the old ball park is most identified with the 1920 World Series, a best-of-nine that Cleveland won in seven. (It was actually known as Dunn Field then;  it was named after the Indians owner at the time.) Also featured were the first World Series grand slam ever, and its first unassisted triple play.

it was named after the Indians owner at the time.) Also featured were the first World Series grand slam ever, and its first unassisted triple play.

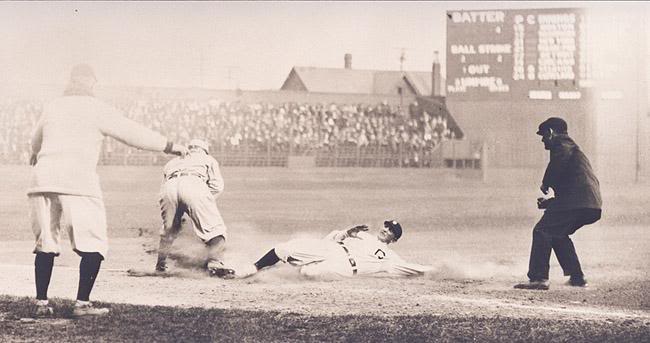

League Park was home to several other milestones. Babe Ruth's 500th career home run and Joe DiMaggio's achievement of hitting in his 56th straight game happened there. (See the Getty Images photo above for DiMaggio, on that day. His streak was snapped the next day, at the Stadium.)

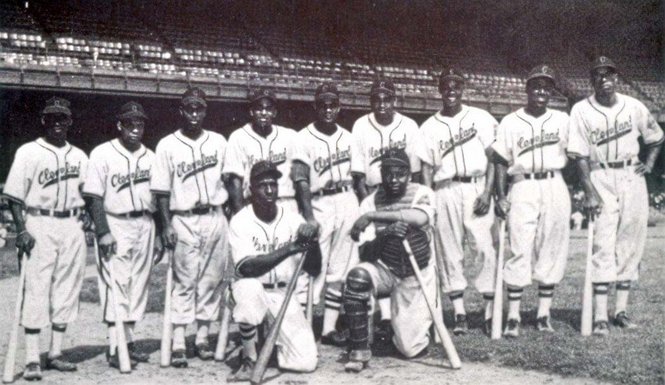

Satchel Paige once said that where he had played on a Negro league team in Cleveland, League Park was visible. He smoldered, wanting to play at that venue. He of course joined the Indians in the championship season of 1948- by then, the club was playing all their home games at the Stadium. A Negro league team by the name of the Cleveland Buckeyes eventually did call League Park home, from 1943 through 1949. They won championships in 1945 and 1947. (Incredibly, in the years of 1947 and 1948, the Cleveland Indians, Cleveland Buckeyes, Cleveland Barons, and Cleveland Browns all won titles.)

Currently, an initiative has been introduced to renovate the grounds of League Park, restoring the field and some of the stands. Here's hoping that gets done.

Here are some more baseball photos related to the old park:

"Shoeless" Joe Jackson:

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

mattvan1 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:19 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)