General

General  General Archive

General Archive  The 20 Biggest Cleveland Sports Stories That Would Have Broken the Internet - Part 3

The 20 Biggest Cleveland Sports Stories That Would Have Broken the Internet - Part 3

A few weeks ago, while at the Indians game with some of our fellow writers at The Cleveland Fan, there was a point in the game where we looked around and seemingly everyone in our group was busy looking down and tapping away on some kind of device.

A few weeks ago, while at the Indians game with some of our fellow writers at The Cleveland Fan, there was a point in the game where we looked around and seemingly everyone in our group was busy looking down and tapping away on some kind of device.

Being the only person in the group without a smart phone made us realize how much technology and social media has changed the way we watch and interact during sports events. We can be at home on the couch, at the stadium or the arena, and still interact with a community of Indians, Browns and Cavs fans across the country and around the world through Twitter, Facebook and e-mail. (And that doesn’t even take into account the numerous high-quality fans sites devoted to Cleveland sports).

That got us thinking about some of the biggest Cleveland sports moments in our lifetime in the pre-blog and social media era, which we are defining as anything before 2004. Because while Syknet may have become self-aware in 1999, sports blogs didn’t become prevalent in town until 2004, the same year Facebook was created, and Twitter did not launch until 2006.

So we came up with the 20 biggest sports stories that would have made the Internet blow up in Cleveland had these various social media platforms existed at the time. Today we present Part Three, highlighting No. 10 to No. 6. (You can find Part One here and Part Two here).

10. The Ted Stepien Era

If there is one thing we know in Cleveland it is bad owners. From slights that are real (Art Modell) to those that are perceived (Randy Lerner, the Dolans), fans love to complain about the owners of the local sports franchises.

If there is one thing we know in Cleveland it is bad owners. From slights that are real (Art Modell) to those that are perceived (Randy Lerner, the Dolans), fans love to complain about the owners of the local sports franchises.

If it wasn’t for Modell (and we’ll get to him in a bit) then Ted Stepien would be at the top of the list as the worst (and certainly most bizarre) owner in Cleveland history.

Stepien bought into the Cavs in the summer of 1980 and things quickly got off to a bad start. In that’s year’s draft, Stepien told coach Stan Albeck to draft North Carolina’s Rich Yonaker (from Euclid) with a high pick because “he knew (Yonaker’s) dad,” according to the 1994 book, Cavs: From Fitch to Fratello. When Albeck mentioned that Yonaker was not a high pick and that North Carolina coach Dean Smith could probably help Yonaker find work, Stepien’s replay of “who’s Dean Smith?” was a sign of things to come for the franchise.

Shortly after Stepien was introduced as owner, Sheldon Ocker, who was covering the Cavs for The Beacon Journal, asked Stepien for an interview. “That would be great,” Stepien replied according to From Fitch to Fratello. “Come on over Sunday after church. We’ll sit around the pool and watch porno films.”

Stepien’s rule as owner was filled with one mistake after another. He hired Bill Musselman as his first coach, even though Musselman had no NBA experience; he eventually ran popular radio broadcaster Joe Tait out of town (see No. 15 on our list); toyed with the idea of renaming the team the Ohio Cavaliers and playing home games in Columbus, Buffalo and Pittsburgh; battled with the media, most notably talk show host Pete Franklin; was so incompetent that the NBA took over running the 1981 All-Star Game; seriously considered moving the team to Toronto; hired Chuck Daly as head coach only to fire him three months later; and in three years as owner saw the team go 28-54, 15-67 and 23-59 while attendance dropped to 2,000 to 3,000 fans a game (on a good night).

But Stepien’s lasting legacy were the trades made during his time.

Under Stepien and Musselman, the Cavs traded away their first round picks in 1983, ’84, ’85 and ’86. In return, they received such notable players as Mike Bratz, Geoff Houston and Jerome Whitehead (who was waived after playing just three games for the Cavs even though the team gave up two No. 1 picks for him).

All the trading led then-NBA Commissioner Larry O’Brien to call a halt to the shenanigans, sending a memo to each team saying the league would have to approve any trade involving Cleveland. That eventually led the league to adopt the Stepien Rule, which prohibits a team from trading No. 1 picks in consecutive seasons.

The franchise was eventually saved by George and Gordon Gund, who bought the team in 1983 ending the infamous run of “Terrible Ted” as owner.

9. Frank Robinson named manager of the Indians

As the 1974 season was coming to a close, Indians team president Ted Bonda was looking to shake things up and bring some interest back to a Tribe team that was headed to another humdrum finish to the season after briefly being in the pennant race.

As the 1974 season was coming to a close, Indians team president Ted Bonda was looking to shake things up and bring some interest back to a Tribe team that was headed to another humdrum finish to the season after briefly being in the pennant race.

When manager Ken Aspromonte resigned in the middle of September, Bonda had his opening. The Indians had picked up Frank Robinson that year on waivers from California and Robinson, nearing the end of his Hall of Fame career, was interested in managing in the majors after spending six years managing in winter ball in Puerto Rico.

So why not get a two-for-one-deal?

“When (general manager) Phil Seghi claimed Frank Robinson on waivers, Phil was simply looking at Robinson as a player,” Bonda said in Terry Pluto’s 1994 book, The Curse of Rocky Colavito. “I immediately thought of him in terms of being our next manager. We needed a drawing card, someone who could bring attention to the franchise. Aspromonte was not about to do that. Frank would.”

Bonda also wanted the Indians to be the team that broke color barrier for managers, just like they broke it in the American League for players with Larry Doby.

“I also felt very strongly about civil rights,” Bonda said in The Curse of Rocky Colavito. “Teams were just reluctant to be the first to hire a black manager. Someone had to go ahead and take the step, and to me it was a privilege to do it. I believed that it was as good a time as any, and that it was terrible that baseball had to wait until 1975 to have a black manager.”

After working out some contract details, the Indians announced that Robinson would be the player-manager starting in 1975, making national headlines. Oddly enough, Doby, who was on the coaching staff when Robinson was hired, was not retained by the new manager.

There was also an economic side to Bonda’s decision, but it turned out that while the move made headlines, it did not equate to a spike in attendance, as the Indians drew less than 1 million fans in each of Robinson’s three seasons.

Robinson had a lot of wear and tear on his body after 19 years in the majors and a bad shoulder meant he would be limited to being a DH in the 1975. He put himself in the lineup, batting second, for Opening Day on April 8 against the Yankees at Municipal Stadium. As talented as he was, Robinson was realistic about his abilities as a 39-year-old.

“I hadn’t hit much in spring training because I found that managing took up so much of my time,” Robinson said in The Curse of Rocky Colavito. I thought maybe I could handle the bat well enough to move the runners along, get a hit to right field.”

The nation’s attention was focused on Cleveland that day, with photographers and reporters from across the country at the game, as well as Commissioner Bowie Kuhn.

With one out in the bottom of the first, Robinson came to the plate. After running the count to 2-2, Robinson hit a home run.

“When Frank hit that home run, the place went insane,” broadcaster Joe Tait said in The Curse of Rocky Colavito. “It was one of the most dramatic moments in sports that I’ve broadcast because we all knew how much pressure was on Frank.”

In a lot of ways that day was the high point of Robinson’s time as manager. He clashed with star pitcher Gaylord Perry, who was traded to Texas midway through Robinson’s first season, and veteran DH Rico Carty; feuded with Tait, who thought Robinson was not a good fit as manager of a young club; struggled to communicate with players not as talented as he was; and was second-guessed by Seghi, who thought himself a talented manager because of his work in the minors in the 1950s.

“Cleveland was not the ideal place for Frank to break in as a manager,” former Indians first baseman Andre Thornton said in The Curse of Rocky Colavito. “Being a black person in a blue-collar town such as Cleveland could not have been easy for Frank. I also think that Phil Seghi and Frank were both going through periods of adjustment. Phil still saw himself as a manager and Frank saw himself as a player because neither was that far removed from it.”

The Tribe fired Robinson during the 1977 season with the team at 26-31. In two-plus seasons as manager, Robinson was 186-189.

“I tell people that I liked Cleveland and they look at me like I’m crazy,” Robinson said in The Curse of Rocky Colavito. “But I did like the town, and I thought overall I did a pretty good job.”

8. Ron Harper traded

The 1986 NBA Draft was a franchise changer for the Cavaliers.

The 1986 NBA Draft was a franchise changer for the Cavaliers.

The team selected Brad Daugherty and Ron Harper in the first round (imagine that, getting two NBA-caliber players in the first round of the draft?) and traded for Mark Price, who was a second-round selection of the Dallas Mavericks.

The trio joined John “Hot Rod” Williams, who had been selected the year before, and Larry Nance, acquired in a trade during the 1987-88 season, to form one of the most entertaining teams in franchise history.

That Cavs team hit its peak in the 1988-89 season, winning 57 games before losing a memorable first-round playoff series to Chicago (see No. 11 on our list). Despite the loss, the future looked bright for a Cavs team that Magic Johnson predicted would be the “Team of the ’90s.”

Harper averaged 19.4 points per game during his first three seasons with the Cavs and gave the team its best chance of beating Michael Jordan and the Bulls. After losing seven of the first eight regular season meetings with Chicago, Harper helped the Cavs win nine of the next 10.

In those days, a Cavs-Bulls game followed a familiar pattern. Daugherty and Price would dominate their positions, Nance would cancel out whoever the Bulls put at power forward, and Scottie Pippen would easily win the battle at small forward.

That just left Harper vs. Jordan.

The Cavs could never slow down Jordan, of course, but Harper made him work and since he was able to score almost 20 points a game, he could offset the clear advantage the Bulls had with Jordan and Pippen and help the Cavs win. (That was one of the best things about going to a Cavs-Bulls game in the late ’80s – you could see Jordan do his thing but also go home happy with a Cavs win).

Despite the playoff loss the previous year, optimism was high for the team heading into the 1989-90 season, but that quickly changed when, just seven games into the season, the Cavs traded Harper, two No. 1 picks and a No. 2 pick to the Clippers for Danny Ferry and Reggie Williams.

The official version of why the Cavs made the trade is because they were not comfortable with the company that Harper was keeping (there is an unofficial version as well, but Google let us down in our search for source material). According to Cavs: From Fitch to Fratello, the Drug Enforcement Administration told the league office that Harper was seen in the company of known drug dealers, that his car may have been used in a drug deal and that Harper may have given the alleged dealers money.

During a meeting to discuss the situation, team owner Gordon Gund demanded that general manager Wayne Embry to make the best deal he could to get Harper off the team immediately. Unfortunately, the rest of the league knew about the allegations as well, which hurt Embry’s ability to make a better deal.

Coach Lenny Wilkens argued against the deal but publically supported it for the good of the team.

“Ron can be out of control at times and do some things that will make you as a coach pull your hair out,” Wilkens said in From Fitch to Fratello. “But he works hard, he’s always on time for practices and planes, and he’s a tremendous talent. Other than Michael Jordan, there isn’t another player in the league who can do what he does when he gets the ball in the open court.”

As for Harper, he recovered from a knee injury with the Clippers to win five titles – three with the Bulls and two with the Lakers – while the Cavs are still looking for their first championship.

“I think we would have won more than one ring (in Cleveland),” Harper said in a 2010 article in The Plain Dealer. “We would have had to beat Chicago, we would have had to beat Detroit, we would have had to beat the Celtics. There were a few teams we would have had to play against, but I felt that we were young enough and naive (enough) to feel that we were that good.”

Unfortunately, in true Cleveland fashion, we never had the chance to find out.

7. Browns cut Bernie Kosar

On Nov. 8, 1993, the unthinkable happened.

On Nov. 8, 1993, the unthinkable happened.

The Browns released Bernie Kosar.

The team announced that day that they were cutting ties with the widely popular Kosar because, in the words of then-coach Bill Belichick, of Kosar’s “diminishing skills.”

In hindsight its hard to argue with that statement, as the increasingly injury-prone Kosar was no longer the same quarterback that took the Browns to three AFC Championship Games in four years in the late 1980s. But when the only other viable quarterback on the roster, Vinny Testaverde, was out with an injury forcing the Browns to start Todd Philcox once Kosar left the building, the timing of the decision was highly suspect. Especially when Philcox actually took the field the following week in Seattle. Philcox, who fumbled his first snap of the game (the Seahawks recovered and returned the fumble for a touchdown), was 9-of-20 on the day for 85 yards and two interceptions. Talk about diminishing skills.

Belichick wanted things done his way with no questions asked, which works all these years later with New England and Tom Brady, but wasn’t the best option back then (a lesson that his coaching tree has yet to learn; it’s OK to do things the Belichick Way when you are Belichick. Everyone else? Not so much). He also rubbed many of the players the wrong way, many of them fan favorites who had won under Marty Schottenheimer.

“We didn’t like Bill,” center Mike Babb said in Jonathan Knight’s 2006 book, Sundays in the Pound. “Bill was mean. Bill hated us. That was the difference. Marty loved us. We were his players.”

The Browns started the ’93 season by winning their first three games, but Kosar was eventually benched in favor of Testaverde. But after Testaverde injured his shoulder, Kosar was back in the lineup, at least temporarily.

Kosar was one of the smartest quarterbacks in the league, which gave him the ability to sometimes make things up as he went along to exploit a defense’s shortcomings (like the last pass Kosar threw as a Brown, a 38-yard touchdown to Michael Jackson against Denver on a play that Kosar changed in the huddle). The fact that Kosar actually wanted to think for himself made it only a matter of when, not if, the quarterback and the coach would clash.

The improvised play may have been the final straw as the team cut Kosar the very next day. Eight years after he came home to Cleveland at a time when no one wanted to play for the Browns (see No. 13 on our list), the Kosar era was over.

The next day’s Plain Dealer devoted most of its front page to the news under a banner headline of “Sacked” with one of the subheds reading “Fans in a Frenzy.” The Beacon Journal called it “The Deepest Cut of All.”

Some hoople heads made threatening calls, forcing the Browns to pay for police surveillance at Belichick’s house and at team headquarters in Berea. “I’m not running for mayor,” Belichick said in published reports. “I’m running a football team, and you can’t make everybody happy. It comes with the territory. I’m sure there will be some discontented fans, but I have to do what’s best for the team and the organization.”

Two days after he was released Kosar signed with Dallas, where he earned a Super Bowl ring as a backup. He then served three years as a backup in Miami, retiring after the 1996 season. Kosar finished his Browns career second on the franchise’s all-time list for attempts, completions, yardage and quarterback rating, and third in touchdown passes.

As for the quarterbacks that Belichick had to have over Kosar, Testaverde took the Browns to the playoffs in 1994 (the last playoff win for the franchise) but found himself out of favor in 1995 and was benched for Eric Zeier. Testaverde would go on to play 12 more seasons.

Philcox was out of Cleveland after the ’93 season and out of football until 1997, when he appeared in two games for the San Diego Chargers.

As for the Browns, they have been looking for their next franchise quarterback ever since Nov. 8, 1993.

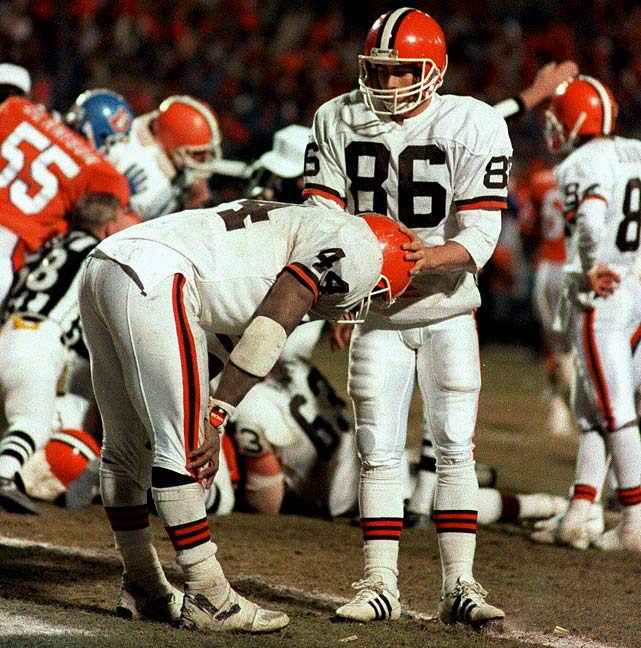

6. 13 Trap

Following the disappointing end to the 1986 season, the Browns came into 1987 ready to take out their frustrations on the rest of the NFL.

Following the disappointing end to the 1986 season, the Browns came into 1987 ready to take out their frustrations on the rest of the NFL.

In the second year of offensive coordinator Lindy Infante’s system, the offense rolled through the league, scoring an average of 26 points a game (third in the league) and beating Pittsburgh by 24 points, Atlanta by 35 and Houston by 33.

The offense was led by quarterback Bernie Kosar, who threw for more than 3,000 yards and 22 touchdowns; receivers Webster Slaughter (seven touchdown receptions) and Brian Brennan (six touchdown catches); and running back Earnest Byner, who gained almost 1,000 yards combined in rushing and receiving and scored 10 combined touchdowns.

The defense was just as good, giving up just under 16 points a game, second in the league, led by Carl Hairston’s eight sacks. Even more impressive was the fact the Browns were playing without four-time Pro Bowl linebacker Chip Banks, who was traded to San Diego on draft day. His replacement? None other than the “mad dog in a meat market,” Mike Junkin.

Things almost came to a halt before they got started as a players’ strike shut the league down after Week 2, cancelling the much-anticipated game with Denver and bringing about replacement players for three games. (The Browns went 2-1 in those games, thanks in large part to Gary Danielson, Ozzie Newsome and Brennan crossing the picket lines to play in the last game, a 34-0 spanking of the Bengals).

The Browns entered the playoffs after winning their final three games of the regular season to clinch their third consecutive Central Division title. In their opening playoff game, they faced the Colts, who had beaten the Browns, 9-7, a month earlier thanks in part to a fourth-quarter Byner fumble on the Colts’ four-yard line (foreshadowing, anyone?)

The teams hit halftime tied at 14, which didn’t sit well with linebacker Eddie Johnson.

“I just got on everybody’s butts and told them we couldn’t play that way in the second half if we were going to win,” Johnson said in Sundays in the Pound. “I said I was tired of coming close and not getting the job done. I said there are no excuses. If you’re good enough, you get the job done.”

The Browns came out a different team in the second half, scoring 24 points to pull away for a 38-21 win to set up a rematch with Denver in the AFC Championship Game.

Things couldn’t have started any worse for the Browns as, on the opening possession, the Broncos intercepted a pass the bounced off the hands of Slaughter. Three plays later, John Elway hit Ricky Nattiel for a touchdown and a 7-0 lead. On their second possession, Kevin Mack fumbled and the Broncos recovered. A few plays later, the Broncos scored on a Steve Sewell run and, suddenly, the Browns found themselves down 14-0.

The Browns calmed down a bit after that, but still went into halftime trailing 21-3.

“This has really been Murphy’s Law time for the Browns,” former announcer Nev Chandler said on the radio broadcast, according to Sundays in the Pound. “Everything that can go wrong has gone wrong and will go wrong. And the Browns have greased the skids with plenty of mistakes on their own behalf.”

The team regrouped at halftime and, once the second half began, the Broncos were powerless to stop the Browns offensive attack (unfortunately, the same could not be said of the Browns defense).

An 18-yard touchdown pass to Reggie Langhorne, a 33-yard touchdown pass to Byner and a four-yard touchdown run by Byner cut the Broncos’ lead to seven entering the fourth quarter. Then, a little more than four minutes into the fourth quarter, Kosar hit Slaughter on a slant for a five-yard touchdown pass.

Suddenly, somehow, the Browns had fought back to tie the game at 31.

After trading punts, the Broncos scored to take a 38-31 lead. The Browns took the field with 3:53 left in the game and an opportunity to pay back the Broncos for the ’86 championship game. Kosar moved the Browns down the field until, with 1:12 left, they faced a second-and-five at the Denver 8-yard-line.

Kosar called 13 Trap and handed the ball to Byner who broke through the left side of the line and headed toward the end zone. Slaughter missed his block on Denver defensive back Jeremiah Castille (something that is often over looked) but Castille still had no chance of stopping Byner. His only option was to try and strip the ball from Byner, and we all know how that turned out.

Afterward, many fans and media members blamed Byner and to this day still carry the misconception that if Byner had scored it would have won the game, rather than just tie it. They also overlook that Byner was the best player on the field that day, totaling 187 yards of offense and scoring two touchdowns.

“I’ve been involved with a lot of teams and a lot of players in my years in this game,” Schottenheimer said in Sundays in the Pound. “But I’ve never been more proud of a group of men than I am today of that group, the Cleveland Browns.”

Little did fans know, as the Browns walked slowly off the field that day at Mile High Stadium, that the team would never be that close to a Super Bowl again.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

HoodooMan (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:36 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)