General

General  General Archive

General Archive  The 20 Biggest Cleveland Sports Stories That Would Have Broken the Internet - Part 4

The 20 Biggest Cleveland Sports Stories That Would Have Broken the Internet - Part 4

A few weeks ago, while at the Indians game with some of our fellow writers at The Cleveland Fan, there was a point in the game where we looked around and seemingly everyone in our group was busy looking down and tapping away on some kind of device.

A few weeks ago, while at the Indians game with some of our fellow writers at The Cleveland Fan, there was a point in the game where we looked around and seemingly everyone in our group was busy looking down and tapping away on some kind of device.

Being the only person in the group without a smart phone made us realize how much technology and social media has changed the way we watch and interact during sports events. We can be at home on the couch, at the stadium or the arena, and still interact with a community of Indians, Browns and Cavs fans across the country and around the world through Twitter, Facebook and e-mail. (And that doesn’t even take into account the numerous high-quality fans sites devoted to Cleveland sports).

That got us thinking about some of the biggest Cleveland sports moments in our lifetime in the pre-blog and social media era, which we are defining as anything before 2004. Because while Syknet may have become self-aware in 1999, sports blogs didn’t become prevalent in town until 2004, the same year Facebook was created, and Twitter did not launch until 2006.

So we came up with the 20 biggest sports stories that would have made the Internet blow up in Cleveland had these various social media platforms existed at the time. Today we present Part Four, highlighting No. 5 to No. 1. (You can find Part One here, Part Two here and Part Three over here).

5. The 1997 Cleveland Indians

Following a loss in the 1995 World Series and a shocking defeat in the 1996 Divisional Series, the Indians and their fans were ready in 1997 for the team to win its first World Series since 1948.

Following a loss in the 1995 World Series and a shocking defeat in the 1996 Divisional Series, the Indians and their fans were ready in 1997 for the team to win its first World Series since 1948.

But this wasn’t the same Indians team. Carlos Baerga had been traded away during the 1996 season (see No. 14 on our list), Albert Belle walked away in free agency to the White Sox and Dennis Martinez was in Seattle. Then, near the end of spring training, the Indians traded Kenny Lofton, who was entering his free agency season, to Atlanta for Marquis Grissom and David Justice.

Despite all the changes, the Tribe was still an offensive force as Jim Thome hit 41 home runs, new third baseman Matt Williams hit 32, Manny Ramirez had 26 to go along with a .328 average, Sandy Alomar had a career year with 21 homers and a .324 average, and Justice added 33 homers and a .329 average. As a team, the Tribe was second in the American League in home runs, and third in batting average and runs scored.

Although they spent 145 days in first place, the Indians would only win 86 games, never winning more than six in a row, in part because of an off-year by the pitching staff. After leading the American League in ERA in both ’95 and ’96, the Tribe slumped to ninth in ’97.

Injuries hit the staff as Jose Mesa missed the first part of the season, Jack McDowell made only six starts and John Smiley, acquired at the trading deadline, was lost in late September when he broke his arm while warming up for a start against Kansas City.

“Just imagine the shock of it,” pitcher Orel Hershiser told The Associated Press. “He was near the end of his warm-ups, just about to go into the game. That means he was throwing well, his arm felt good. If you’re getting some pain, you’d be starting to back off. But he was feeling fine and going after it. And then all of a sudden . . . ”

“You could see it was deformed through the skin,” reliever Jason Jacome said. “He was in extreme pain. He was yelling. I’m sure it was agony. I hope I never have to see something like that again.”

The bright spot in the starting rotation was rookie Jaret Wright, who went 8-3 after being called up in late June.

But all that was just a tasty prelude to what would turn out to be one of the wildest and most unpredictable postseasons in Cleveland sports history.

The Indians took on the favored Yankees in the Divisional Series and fell behind two games to one after David Wells shut them down in Game 3. Things didn’t look good when the Yankees took a 2-1 lead into the bottom of the eighth inning of Game 4 – especially with Mariano Rivera on the mound.

With two outs, Alomar drove a pitch for a game-tying home run and, after a 1-2-3 ninth inning from Michael Jackson, the Indians pulled out the win in the bottom of the ninth when Omar Vizquel singled home Grissom.

In Game 5, the Tribe jumped out to a 4-0 lead against Andy Pettitte, the most-overrated postseason pitcher in history, only to see the Yankees rally to within one run after six innings. In the ninth inning, Mesa got two quick outs before Paul O’Neill drilled a double off the center-field wall to put the tying run in scoring position. But Mesa got Bernie Williams to fly out to center and the Indians were heading to the American League Championship Series against Baltimore.

If fans thought they had seen it all against the Yankees, they had no idea what was coming.

After splitting the first two games in Baltimore, thanks to a three-run home run by Grissom in the eighth inning of Game 2, the Tribe returned to Jacobs Field for an almost five-hour Game 3.

Matt Williams broke a scoreless tie in the seventh with an RBI single, but the Orioles came back in the top of the ninth against Mesa (ahem) as a Brady Anderson double tied the score and sent the game into extra innings. The Tribe pulled out the win in the bottom of the 12th when Grissom stole home on a missed suicide squeeze attempt by Vizquel.

Game 4 was another tense game as the Indians fell behind 5-2 after three innings, rallied to take a 7-5 lead after five innings, before seeing the Orioles score in the seventh inning and ninth inning (off Mesa again) to tie the game at 7. In the bottom of the inning, with two on and two out, Alomar singled home Ramirez and the Indians suddenly had a 3-1 lead in the series.

After a pedestrian Game 5 where the Orioles won, 4-2, the teams headed back to Baltimore for Game 6. The Orioles and Indians took a scoreless tie into the 12th inning before Tony Fernandez took Armando Benitez deep for the game’s first (and only) run. Mesa managed to seal the deal in the bottom of the ninth and the Tribe was headed back to the World Series for the second time in three years.

The Indians taught their fans a painful lesson in the World Series against the Marlins – if you are going to alternate wins in a seven-game series, it doesn’t help to win the even-numbered games.

Despite some bumps along the way, including a 14-11 Florida win in Game 3 that included 17 walks, six errors and an 11-run ninth inning, the Tribe managed to take a 2-1 lead into the bottom of the ninth inning of Game 7 and turned the game over to Mesa.

Moises Alou singled to lead off the inning, advanced to third on a base hit by Charles Johnson and scored on a Craig Counsell sacrifice fly to tie the game and force only the third extra-inning Game 7 in World Series history.

The game went to the bottom of the 11th where Bobby Bonilla led off with a single. After a failed bunt attempt, Fernandez booted a potential double-play ball, allowing Bonilla to move to third. After an intentional walk and a force play at the plate, Edgar Renteria singled home the winning run, ending the Tribe’s best chance to date of winning a World Series.

And, really, what’s more Cleveland than losing a World Series in an historic fashion?

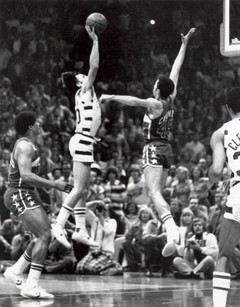

4. The Miracle of Richfield

The 1975-76 Cavaliers came along at the perfect time. The Indians were in the early stages of a two-decade funk and the Browns were struggling through the first extended down period in franchise history.

The 1975-76 Cavaliers came along at the perfect time. The Indians were in the early stages of a two-decade funk and the Browns were struggling through the first extended down period in franchise history.

That’s why the Miracle of Richfield was even more, well, miraculous.

The Cavs had slowly been putting together a solid team and had missed making the playoffs the previous year on the final day of the season. The team started the season off with a bit of a hangover and sat at just 6-11 near the end of November.

“Nothing was clicking,” center Jim Chones said in Cavs: From Fitch to Fratello. “It was almost like we were tired from the year before, when we had come so close to making the playoffs. There were some petty jealousies. Guys were questioning (coach Bill) Fitch. All the things that eventually can tear a team apart were being set in place.”

That all started to change when the Cavs traded for 34-year-old center Nate Thurmond, who brought a much-needed veteran presence to a young team that was still learning how to win.

“(Nate) said that we had the ability to win a championship, but there was a problem, we didn’t believe in ourselves,” guard Austin Carr said in From Fitch to Fratello. “From that moment, we all changed. (Nate) had the unique ability of making guys believe in themselves.”

Thurmond helped Fitch build a solid rotation, with Chones, Bingo Smith, Jim Brewer, Jim Cleamons as the starters, with Thurmond, Carr, Foots Walker and Campy Russell coming off the bench (how’s that for depth?). Fitch got everyone to buy into the greater good and it paid of as once everyone settled in the Cavs ran off a stretch where they won 10-of-11 games. The Cavs were 43-22 after the Thurmond trade and won their first Central Division title (a feat they would not repeat for more than 30 years).

Once the team started winning the fans responded, and not in a corporate, “we’re going to the game to be seen” kind of way (after all, Cavs games were rarely on TV back then).

“It was just the fans going nuts,” longtime broadcaster Joe Tait said in Joe Tait: It’s Been a Real Ball. “They didn’t have an electronic scoreboard or cheerleaders, or some guy in the middle of the court screaming into a microphone. They did it on their own. They loved that team because they watched it grow up – and then saw a local guy in Nate come home to lead them.”

The Cavs drew the Washington Bullets for the first playoff series in franchise history. The Cavs would play 13 playoff games over the next month that would rival anything seen in Cleveland sports history (short of a championship) for excitement.

After dropping the opener at home, Cleveland won Game 2 when Bingo Smith hit a 25-footer with two seconds left. The teams split the next two games to set up a pivotal Game 5 at the Coliseum.

The Cavs trailed by one with seven seconds remaining. After Washington’s Elvin Hayes missed two free throws that would have iced the win (no 3-point shots back then), Smith put up an airball from 14 feet that Cleamons rebounded and put in for the winning basket. In Game 6, the Cavs fought back from 17 down to force overtime, but the Bullets pulled out the win to send the series back to the Coliseum for Game 7.

With nine seconds remaining and the game tied at 85, the Cavs inbounded the ball to Snyder who drove to the hoop and scored with four seconds left. The Cavs had to sweat out one last shot from the Bullets before they could celebrate their first playoff series win. The fans also joined in the celebration as they stormed the court (can anyone imagine that happening today at a Cavs game?).

“I have never experienced anything like that in my life,” Carr said in From Fitch to Fratello. “I remember looking over my shoulder and seeing people coming at me. The noise, I’ll never forget the noise.”

The Cavs moved on to face an aging Boston Celtics team in the Eastern Conference Finals. But in a true This is Cleveland moment, Chones broke his foot in the final practice before the series.

After losing the first two games, thanks in part to Thurmond fouling out with more than seven minutes to play in Game 2 on the type of non-foul the Celtics have lived off of for decades, the Cavs took the next two at home, including a Game 4 rout.

But that was the last good moment for the team as time (and the officials) finally caught up to Thurmond, who was forced to play close to 40 minutes a game in the series. In Game 5, Thurmond somehow had four fouls by the second quarter and, in Game 6, the Celtics experience finally wore down the Cavs.

“The sad part about this is that I was more sure of beating Boston than I was of beating Washington,” Chones said in From Fitch to Fratello. “(Boston) got a lot of easy baskets. No one got easy baskets when Nate and I were out there.

“These players today have no idea what it is like to be cheered by a crowd that is totally in love with you.”

“The fans needed something to latch on to and we were it,” Cleamons said in the book. “It was true joy and enthusiasm.”

3. The Drive

No one really knew what to expect from the 1986 Cleveland Browns.

No one really knew what to expect from the 1986 Cleveland Browns.

Sure, the team won the AFC Central Division title in 1985, but with just an 8-8 record behind a ground-and-pound offense that was 23rd in the league in scoring and that would have fit comfortably in the 1950s. And, yeah, the team made the playoffs in ’85, losing to Miami after holding a 21-3 lead.

That all changed, though, under new offensive coordinator Lindy Infante, whose system fit quarterback Bernie Kosar’s style perfectly and helped the Browns move to 5th in the NFL in scoring in 1986.

The Browns split the first four games of the season, but fans realized this was going to be a special season when the team traveled to take on the Steelers in Week 5 at Three Rivers Stadium – a place where the Browns had never won. But behind Gerald McNeil’s 100-yard kickoff return for a touchdown and a timely fumble recovery by Chris Rockins, the Browns finally broke the Three Rivers jinx.

The team finally took off after a loss to Green Bay dropped the Browns to 4-3 on the season. The team closed out the year by winning eight of its last nine games – including consecutive overtime wins over the Steelers and Oilers – to finish the year at 12-4 and earn homefield advantage in the AFC playoffs.

The Browns hosted the Jets for their first home playoff game since Red Right 88 (see No. 12 on our list) and the fans responded, buying the 40,000 available tickets in less than two hours and believing that this time it would be different.

“In 1980, guys had been around a while. I think there is more talent on this team overall and definitely more depth,” tight end Ozzie Newsome, who played on both squads, said in Jonathan Knight’s 2006 book, Sundays in the Pound. “This team has endured more adversity. I would characterize 1980 as a Hollywood team. This is a blue-collar team.”

Of course, they weren’t so blue collar that they couldn’t make the historically ridiculous Masters of the Gridiron video.

Newsome was right about the Browns facing adversity, especially in the playoff game against the Jets, which gave fans the hope that maybe this was going to be a different year for Cleveland.

The teams were tied at 10 at the half, but the Browns struggle to get anything going on offense in the second half and, after a Freeman McNeil touchdown run, the Browns found themselves on the wrong end of a 20-10 score with 4:14 remaining.

On the following possession, the Browns faced a second-and-24 from their own 17 and thanks to a Mark Gastineau roughing the passer penalty (bless you, Mark) the Browns finally woke up and Kosar moved the team down the field, with Kevin Mack scoring a touchdown to cut the lead to 20-17. The defense held, giving the Browns one last chance with 53 seconds left.

After a pass interference call moved the ball to the Jets’ 42, Kosar hit Webster Slaughter down the left sideline to set up Mark Mosley’s game-tying field goal and send the game into an improbably overtime.

Even though it took until the second overtime for the Browns to win, after the improbable comeback the outcome never seemed in doubt.

“I think about that game a lot,” receiver Reggie Langhorne said in Sundays in the Pound. “I think about that game when things look bad. I think about it and it motivates me.”

The win put the Browns into the AFC Championship Game with Denver, and if fans thought they had seen it all against the Jets, they were in for a painful surprise.

The Browns opened the scoring on a six-yard touchdown pass from Kosar to Herman Fontenot. The game went back and forth until Kosar hit Brian Brennan with a 48-yard touchdown pass with a little more than five minutes left. On the ensuing kickoff, the Browns pinned Denver at its own two-yard line and, holding a 20-13 lead, the Browns never seemed closer to the Super Bowl than at that moment in time.

We won’t go into detail about what happened the rest of the game (even 26 years later it is still too painful) other than to say no one will ever convince us that Rich Karlis’ field goal was good. Even Karlis knows it, saying “thank God they don’t have instant replays on field goals,” according to Jonathan Knight’s 2008 book, Classic Browns.

“It was like my heart dropped out of my chest,” defensive lineman Bob Golic said in Sundays in the Pound. “I remember laying there in the mud and the dirt and couldn’t believe it was over. I don’t think I’ve ever felt so down.”

The nearly 80,000 fans in attendance and countless more watching on TV felt the same way.

2. The 1995 Cleveland Indians

Cleveland Indians fans had waited 41 years to see the Tribe play in a World Series, so what were a few more weeks?

Cleveland Indians fans had waited 41 years to see the Tribe play in a World Series, so what were a few more weeks?

After a players strike cut the 1994 season short with the Indians trailing the White Sox by just one game in the newly created AL Central Division, Tribe fans had to wait just a bit longer as the strike also wiped out the first 18 games of the ’95 season.

But once the games started, the Indians put on a performance that, even in the steroids era, was impressive.

With 100 wins in 144 games, the Tribe lead the league in batting average (.291), home runs (207), runs (840) and ERA (3.83). The Indians went from 1.5 games out of first to a ridiculous 30 games in front of second-place Chicago by the end of the season, clinching the division on Sept 8. Along the way they won 28 one-run games and 27 games in their final at-bat.

The offense steamrolled through the opposition, as Albert Belle hit .317 with 50 home runs, 50 doubles and 126 RBI; Carlos Baerga hit .314; Jim Thome had 25 home runs and a .314 average; Kenny Lofton hit .310 with 54 stolen bases; Manny Ramirez had 31 home runs and a .308 average; and Eddie Murray hit .323 with 21 home runs.

As dominant as the Indians had been during the season, the legacy of Cleveland sports loomed over the team as the playoffs got under way.

“At the start of the season, I know a lot of people picked us to win the division, but I don’t know how many people really believed it,” former manager Mike Hargrove said in Terry Pluto’s 1995 book, Burying the Curse. “I heard a guy call a talk show and say, ‘If the Indians don’t get to the World Series, it will be the Browns and The Drive and all that.’ I understand the mentality about wanting to win the World Series, but I’m not going to sit here and say, ‘If we get beat in the first round of the playoffs, the season has been a failure.’”

Because of the absurdity of the way baseball sets up its postseason, the Indians did not have home field advantage for any round of the playoffs. But that may have actually worked to their advantage in the opening series against Boston as the inexperienced Indians hosted the first two games of the best-of-five series at Jacobs Field.

After waiting so long for postseason baseball to return to Cleveland, the Tribe and the Red Sox gave the fans a treat, as the Tribe rallied for three runs in the bottom of the sixth inning to take a 3-2 lead. The game eventually went into extra innings with Boston’s Tim Naehring giving the Red Sox a one-run lead with a home run in the top of the 11th. But Belle answered back with a clutch home run of his own in the bottom of the inning (and had his bat confiscated after Boston manager Kevin Kennedy complained to the umpires) before Tony Pena finally ended the night at 2:08 a.m. with a home run with two outs in the bottom of the 13th inning.

It was the first home playoff win for the Indians since 1948, but not the last.

Orel Hershisher and three relievers combined to shutout the Red Sox in Game 2 and Charles Nagy threw seven innings of one-run ball in Game 3 to complete the sweep.

The Indians and the Mariners split the first four games of the AL Championship Series, setting up a key Game 5 at Jacobs Field. Lose and the Indians faced the prospect of heading back to Seattle needing to win both games.

Pitching carried the day for the Tribe as Hershisher worked six innings, giving up just one earned run and striking out eight. But the biggest inning of the game – and possibly the season – was turned in by Paul Assenmacher in the top of the seventh.

With runners on first and third with one out and the Tribe holding on to a 3-2 lead, Assenmacher got Ken Griffey and Jay Buhner to strike on swinging as Jacobs Field exploded.

The Indians held on for the win, beat the Mariners in Game 6 – thanks to Lofton’s dash home from second base on a wild pitch and Dennis Martinez’ seven scoreless innings – to finally return to the World Series. It was the first time in many fans’ lives that a Cleveland team would actually play for a championship.

The Tribe opened on the road (again) against the Braves, dropping the first two games of the series in one-run contests. They returned home and in a fashion befitting the season, took Game 3 in extra innings on an Eddie Murphy RBI single in the bottom of the 11th.

The Indians came up short in Game 4, missing out on an opportunity to tie the series. They rebounded to win Game 5 and headed back to Atlanta needing a sweep of the final two games.

Game 6 was another tension-filled game. The Indians could only manage one hit in the game but somehow the game remained scoreless going into the bottom of the sixth inning. But then David Justice hit a 1-1 pitch from Jim Poole into the right-field stands for a leadoff homerun.

Even though the Tribe still had nine outs to go, the series and the season were essentially over.

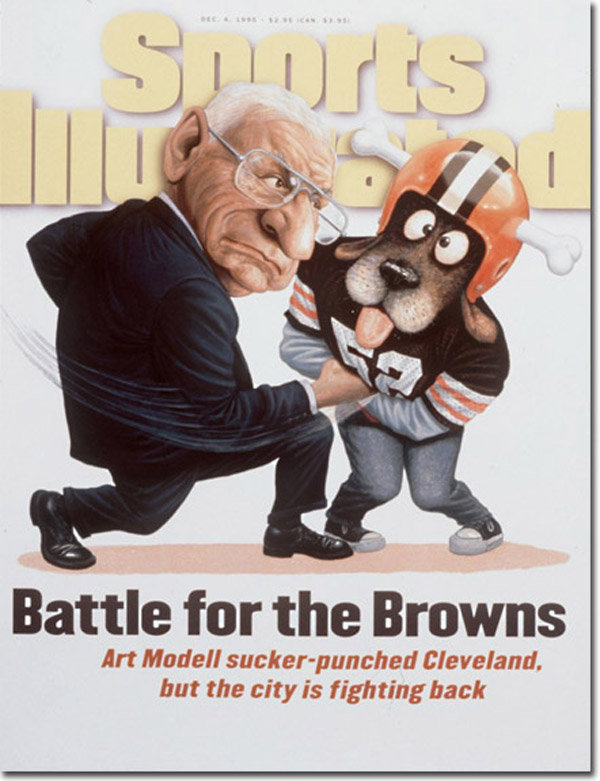

1. The Browns move to Baltimore

The NFL is a great sport if you are an owner.

The NFL is a great sport if you are an owner.

Sure, the rosters are the largest of any American sport, but you don’t have the guaranteed contracts that hamstring franchises in other sports. You play once a week in (mostly) sold-out stadiums and equal revenue sharing, combined with a hard salary cap, means that television money covers your player expenses – easily the biggest expense on a team’s ledger.

Basically, it is pretty much impossible not to make money if you are one of the 32 people lucky enough to own an NFL franchise.

Unless you are Art Modell, that is.

Modell famously moved the Browns to Baltimore because he somehow could not find a way to turn a profit in Cleveland – a town so football crazy that you could probably put an Orange helmet at midfield and people would come to the stadium to watch. He couldn’t make it work with a fan base that is so obsessed they worry about what color uniform the team will wear. A fan base that only wants to cheer for “a hard working team from a hard working town.”

For the nine-year stretch preceding 1995, the Browns averaged more than 70,000 fans a game. Local TV ratings were among the highest in the league, with the Browns finishing second (to the Dallas Cowboys) in 1993 and first in the league in 1994.

Somehow, someway, Modell couldn’t make it work under those conditions. And he was always good at placing the blame elsewhere for his financial shortcomings, including:

- The media: “I don’t know if the Browns can continue to compete in an area where there is so much media hostility toward the team,” Modell said in the 1997 book, Fumble! The Browns, Modell and the Move. “I can’t say if we’ll move or we won’t move ... What does bother me is that I think some of that (criticism from the media) is influencing our fans.”

- Local corporations: Modell believed local businesses were abandoning the Browns so they could support the Gateway project that was building Jacobs Field. Rather than blame the team’s performance and the growing discontent among fans with coach Bill Belichick.

- The city of Cleveland for not helping out with the stadium: “I wouldn’t consider moving the team. Newspapers have been making more out of that than they should,” he said in Fumble! “I do, however, believe Cleveland Browns fans deserve equal treatment as the Indians and the Cavs fans. I am not asking for a new stadium. I’m just asking for help to refurbish, in a major way, the current stadium. If I don’t get a new stadium or a refurbished stadium by the end of the contract, I’m not going to move the team.”

There is probably some truth in Modell’s words, especially his criticism of Cleveland city officials. While it is hard to argue that the Indians desperately needed their own ballpark, there was no reason to build Gund Arena as the Cavs had a perfectly suitable home at the Coliseum. But Cleveland did not receive any tax dollars from events at the Coliseum, so greed led them to build an arena that they didn’t need and leave Modell feeling like the kid not invited to the cool party.

It doesn’t help, either, to look back and realize the Modell was out foxed by Mike Brown of all people. When Baltimore went trolling for an NFL team that they could steal from another city, the Cincinnati Bengals were on the list as they were in a similar situation as the Browns. The Cincinnati Reds were getting a new baseball stadium and the Bengals were wondering when it would be there turn.

According to the 1997 book, Glory for Sale: Fans, Dollars and the New NFL, Brown made it clear to Cincinnati city officials in May 1995 that the Bengals wanted a “new, grade-A facility” or else the team would consider its options, including moving to Baltimore. That June, Brown traveled to Baltimore for a “secret” meeting with John Moag, chairman of the Maryland Stadium Authority. When several camera crews from Cincinnati TV stations filmed Brown walking off the plane in Baltimore for the “secret” meeting, Brown reiterated that he was exploring all his options.

Brown’s PR gambit worked as, within a few weeks, city and county officials around Cincinnati put together a sales tax plan to pay for not only a new park for the Reds but also a new stadium for the Bengals.

Perhaps if Modell had been more open about his flirtations with Baltimore, rather than doing everything on the sly (like asking for a moratorium until the 1995 season was over will continuing to talk to Baltimore), Cleveland officials would have realized the Browns were an incredibly higher priority than stealing the Cavs from Richfield. “What got to us was the treatment basketball and baseball were getting ... we were fifth man on the totem pole,” Modell said in Glory for Sale.

Maybe if the city had taken the matter more seriously, we never would have witnessed the events of Nov. 6, 1995, when Modell sat in a parking lot in Baltimore with the grinning idiot Gov. Parris Glendening gleefully announcing that Baltimore had taken the Browns from Cleveland.

Baltimore gave Modell the sweetest of sweetheart deals: the state would pay for a new stadium that the team would use rent free; the team would keep all profits from parking, concessions, tickets, skyboxes and advertising, and the team could sell up to $80 million in Personal Seat Licenses.

Of course, Modell being Modell, he squandered the opportunity and ended up having to sell the team anyway, agreeing to a deal in 1999 with Stephen Bisciotti that would have Bisciotti take total control of the franchise by 2004.

And that is perhaps the saddest part of this tale. Modell decided that to save the franchise he had to move the franchise, but in making a deal with the devil he lost not only the team but the love of his adopted hometown of Cleveland. If only he’d sold a majority interest in the Browns to someone local (Al Lerner, perhaps, who somehow gets a pass on his role in the move) while retaining a small portion for himself, Modell would have gone down as one of the best owners in Cleveland sports history. Especially if it would have been the Browns, rather than the Ravens, lifting the Super Bowl trophy following the 2000 season.

In some ways, that makes this the most Cleveland story of them all.

- NBA Announces 2013-2014 Schedule

- Browns Ink Sharknado

- Sharknado A No-Show For Rookie Camp

- Trent Richardson Out Until Training Camp

- Browns Sign Brandon Jackson

- Carrasco Suspended Eight Games

- Browns Add to Wide Receiver Depth with David Nelson

- Browns Need to Learn from Past Draft Mistakes

- Browns Release Chris Gocong and Usama Young

- Browns Missing on Grimes Disappointing, But Not The End

The TCF Forums

- Official- Browns Coach Search/Rumors

HoodooMan (Tuesday, January 21 2014 1:36 PM) - Movies coming out

rebelwithoutaclue (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:56 PM) - 2015 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:38 PM) - The 2014 Offseason Thread

Larvell Blanks (Tuesday, January 21 2014 12:25 PM) - Chris Grant's first 3 drafts

Kingpin74 (Tuesday, January 21 2014 10:13 AM) - Mike Brown

YahooFanChicago (Monday, January 20 2014 11:15 PM) - 2014 Hoops Hockey Hijinx

jpd1224 (Monday, January 20 2014 4:44 PM) - 2014 Recruiting

jclvd_23 (Monday, January 20 2014 2:26 PM) - Wish List - #4 Pick

Hikohadon (Monday, January 20 2014 1:26 PM) - #1 overall pick Anthony Bennett

TouchEmAllTime (Sunday, January 19 2014 1:28 PM)